I find myself staring at the screen, unable to comprehend how utterly devastating it must be as a parent, to have a police officer knock on your door in the early hours of the morning, to be told that your darling child has been stabbed to death. My heart weeps for the senseless loss of life, young lives stolen away in this rising tide of violence. I know what it is like to break truly awful news to people and their families and my heart goes out to the police officers on the beat or the clinicians in the Emergency Department, who have to break the terrible news to the parents and the siblings, that so suddenly, a bright shining light in their lives, has been extinguished.

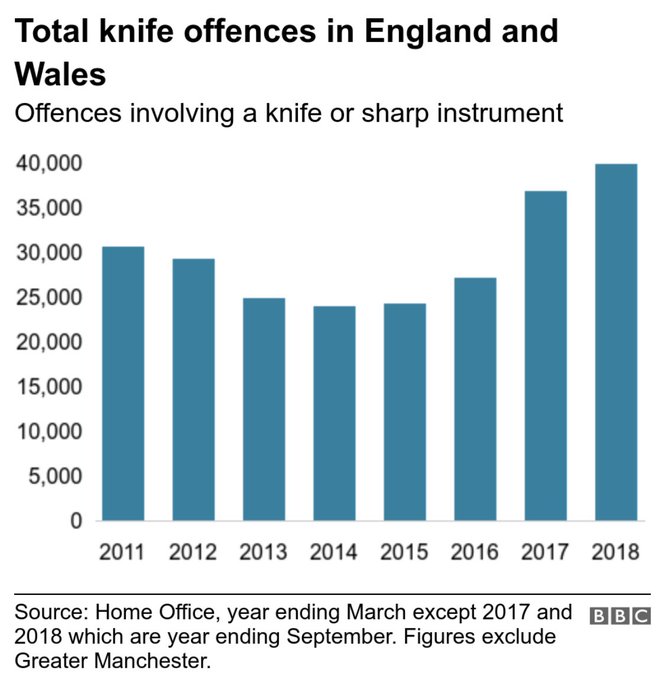

Knife attacks are a crime, there is no denying that, but the burden of guilt is not so easily apportioned. We are seeing an exponential rise of it in our streets, with a 93% increase in recent years across England, whilst in Scotland, they have seen a 64% decrease over a similar timeframe. We need to examine what has gone on in that time and ask some very uncomfortable questions. We also need to call people to account for decisions which have been made, despite knowing the evidence, and we desperately need a ‘whole systems’ approach to tackling this epidemic.

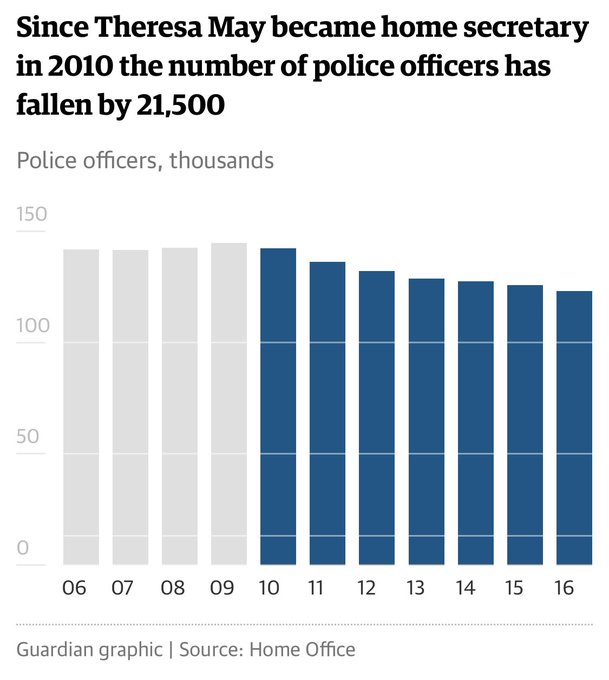

The Primeminister has stated that “knife crime” is not linked to a decrease in policing numbers. The police chiefs disagree. The truth is, that it’s not only the police who have disappeared off our streets (and these are community police officers, who knew their communities well and were respected and trusted – it takes years to build up those kind of relationships) – we’ve had a perfect cocktail of cuts right across the board which is directly attributable to the mess we are now in. Ongoing austerity, which is a political choice, has also led to the closure of youth centres, more young people than ever excluded from school, (who then have a 200 times higher chance of being groomed into violent gangs) and massive cuts to public health and local government, meaning many preventative schemes have disappeared. When policy fails, it has to be called out and challenged. Everyone with a brain knows that prevention is better than cure. And for those who have lost loved ones, there is now no comfort – this could have been prevented, but has been allowed to escalate at such an alarming rate because we do not have a form of politics or leadership that listens to what is really going on in our communities, but continues to drive through ideological changes without thinking through the consequences. This is unacceptable.

The Primeminister has stated that “knife crime” is not linked to a decrease in policing numbers. The police chiefs disagree. The truth is, that it’s not only the police who have disappeared off our streets (and these are community police officers, who knew their communities well and were respected and trusted – it takes years to build up those kind of relationships) – we’ve had a perfect cocktail of cuts right across the board which is directly attributable to the mess we are now in. Ongoing austerity, which is a political choice, has also led to the closure of youth centres, more young people than ever excluded from school, (who then have a 200 times higher chance of being groomed into violent gangs) and massive cuts to public health and local government, meaning many preventative schemes have disappeared. When policy fails, it has to be called out and challenged. Everyone with a brain knows that prevention is better than cure. And for those who have lost loved ones, there is now no comfort – this could have been prevented, but has been allowed to escalate at such an alarming rate because we do not have a form of politics or leadership that listens to what is really going on in our communities, but continues to drive through ideological changes without thinking through the consequences. This is unacceptable.

When Heidi Allen MP came to Morecambe, she heard the testimony of my friend, Daniel, who grew up in some really tough circumstances, forced into a gang culture in order to help put food on the table and prevent harm coming to his family. Tears streamed down her face as she heard his powerful account of what it meant for him as a young person, to have his youth centre closed, his local high school closed and being told he was not a priority when he was street homeless. She told us that she had not realised the layers to the poverty that many are experiencing across England. And this is how the (perhaps) unintended consequences of remote policy decisions affect ordinary people in droves across the UK. When school budgets are cut and mental health teams are cut and social care provision is cut and youth centres are cut, children and young people from home environments which are already struggling to make ends meet, already processing significant trauma and adversity, fall prey to gangs and criminal networks who use them and abuse them for their gains across county lines.

When Heidi Allen MP came to Morecambe, she heard the testimony of my friend, Daniel, who grew up in some really tough circumstances, forced into a gang culture in order to help put food on the table and prevent harm coming to his family. Tears streamed down her face as she heard his powerful account of what it meant for him as a young person, to have his youth centre closed, his local high school closed and being told he was not a priority when he was street homeless. She told us that she had not realised the layers to the poverty that many are experiencing across England. And this is how the (perhaps) unintended consequences of remote policy decisions affect ordinary people in droves across the UK. When school budgets are cut and mental health teams are cut and social care provision is cut and youth centres are cut, children and young people from home environments which are already struggling to make ends meet, already processing significant trauma and adversity, fall prey to gangs and criminal networks who use them and abuse them for their gains across county lines.

And yet in Scotland, we are seeing an altogether different picture emerging, because they saw this problem 10 years ago and decided to make a difference by dealing with complex living systems, rather than tinkering clumsily with mechanistic thinking. So it is high time that England ate some humble pie and learnt from our Celtic friends.

Scotland, unlike the English, are not delaying on taking a serious approach to Adverse Childhood Experiences, hoping to become the first fully trauma informed nation in the world. They have taken a public health, holistic approach to the knife crime problems in Glasgow and then spread the learning across the nation, rather than making devastating cuts to their PH budgets. What they have done isn’t rocket science – it’s plain, public health common sense. They have chosen not to criminalise, label and stigmatise young people (something the hostile environment rhetoric seems to do). They have refused to see it as a race problem – because it isn’t (but some in our press in particular, and some members of the government have stirred up this nonsense anyway) and they have invested in early and effective youth intervention programmes, amongst other things.

One of things my work has taught me to do, is suspend my judgements of those who we would automatically and ordinarily point the finger at, the supposed perpetrators of a crime, and really listen to the truth. The truth here is complex and I’m not saying that people who commit violent acts do not need to face the consequences of their actions. They do. But what I am saying is that we need restorative justice in our communities that breaks this horrendous cycle. We also need to recognise that there has been terrible violence done to our most vulnerable children and young people across England by a series of political decisions. The government has failed those it should have protected. In my line of work, those kind of errors would lead to massive learning events and the dismissal of those who had failed in their leadership. Perhaps people have such little faith in the political system we have because there is seemingly such little accountability. Now is not the time for silly political defence of failure. Now is the time for humility, repentance and a genuine turning of the hearts of the fathers and mothers in the nation to the rising generation, far too many of whom are no longer with us.