Is the decision to send some of our children back to school on June 1st the right one? What are the factors that have been considered and how has the decision been made? I”ve been asked these questions a number of times and they bother me at several levels. They bother me as a Dad (and believe me I have an even deeper respect for teachers and the magic they do every day!), as a GP, as a School Governor of a Primary School, as a Trustee of a Multi-Academy Trust, as a Co-Author of a book about Adverse Childhood Experiences and as a local leader in the NHS as Director of Population Health in Morecambe Bay. So, I come to the questions with several different hats on and feeling conflicted in how I think about the issues involved. To be absolutely clear, this blog is written from a personal perspective and I am not writing in any of my official capacities, as with any blog on this site. I was having a conversation the other day with a friend of mine, who spent years working as a solicitor. We were talking about judicial reviews and the probity of any given decision. The vital test is this: has everything been taken into account that should have been; has anything been taken into account that shouldn’t have been? In other words, it’s not about the decision but about HOW the decision is arrived at. If the test is satisfied, it’s a good decision.

Firstly, I want to focus on the process of decision making. Over the last few years, working with the Poverty Truth Commission and using the ‘Art of Hosting’ as a framework for how to encourage wider participation, I have been greatly impacted in how I think about this process. In the PTC we follow the basic principle that ‘no decision about me, without me, is for me’. When the government made the decision to open schools more widely on June 1st, did they talk to the unions first? Did they discuss the ideas, concerns and expectations of many teachers prior to their announcement? Was there any discussion with children or young people about what they might feel about returning to school and what their priorities might be? Was there even an announcement to the house of commons so that the idea could be debated and discussed before deciding on the June 1st date? I think the answer to each of those questions is ‘no’. So, in terms of probity, it seems impossible to say this is a good decision without having taken into account such vital opinions and voices. I absolutely recognise that being in government at such a time is no easy task. If the government, here in the UK, continue to act without involving wider participation and conversation, it is less likely, especially at a time of such national anxiety and uncertainty, that they will be able to take the public with them. We need the government to choose to be listening, inclusive and honest about the complexity of the issues involved. If they do this, they will find national collaboration much easier to achieve.

Secondly, we keep being told by the government that we are being “guided by the science”. This statement alone poses so many questions! When Sir Jeremy Farrar, (watch from 10:30) CEO of The Wellcome Trust, and member of SAGE was humble enough to admit last week that it was a mistake not to have been far more on the front foot with testing and contact tracing here in the UK, something which has been shown to have an extraordinary benefit in Kerala, South Korea, Taiwan, Iceland and Germany (as just five examples – there are plenty of others from Africa and Oceana also), it felt like there was a collective sigh of relief across the country. Finally, someone actually publicly stated that things have gone wrong. Since that time Prof Tim Spector has warned us that because the UK has been listing only a limited number of possible Covid-19 symptoms, there are probably between 50000 and 70000 people who currently have the disease and are not self-isolating. He, along with Deputy Chief Medical Officer, Professor Jonathan Van Tam have both also insinuated that the ‘tried and tested’ method of physical contact tracing through local public health teams is much more trustworthy than a centralised app-based model. Without this, the ‘R’ number is very limited in it’s ability to predict much at all, as we’re really in the terriotry of good guess work, rather than more real time data which we can interrogate and probe more thoroughly. The danger with this approach therefore is that we are 3-4 weeks behind with the actual numbers and looking at death rates doesn’t necessarily help us much either when considering the rate of spread. To make matters more complex, the (inaccurate) R number has significant regional variation, which again makes the case for more locally led and connected decision making. Furthermore, the UK Pariliament’s Science and Technology Committee, chaired by the Rt Hon Greg Clark MP have detailed ten significant findings and concerns with recommendations attached, whilst recognising the complexities involved. Of particular note, we’ve had 10 weeks in which woefully insufficient testing, contact tracing and isolation has been the reality. Today, the WHO reported the largest number of new cases of Covid-19, worldwide. With our airports still open and an increase in travel emerging, we put ourselves at major risk of an early second wave, especially if we do not have the necessary systems in place to prevent this. Boris Johnson is still adamant that things are steaming ahead nicely but other government ministers say their new track and trace system will not be ready for roll out on June 1st. This is different to having a fully operational system in place. There are questions that still demand answers! Many expert voices are calling for a much more locally driven, joined up approach, led by our brilliant Directors of Public Health, supported by joined up working across the public sector and supported by General Practice. There are plenty of voices asking us to pause and think again.

Thirdly, we need to know if it safe for children to go back to school? The government are confident and clear that it is. It is interesting, however, that allegedly every member of the current cabinet sends their children to private schools, none of which will be opening until September. The answer to this question is not straightforward and there are several things to consider and we should be honest about that. Are children likely to become unwell from Covid-19, if they have no underlying health conditions? No – they are very likely to only suffer very mild symptoms, though there are some concerns regarding some children having rare sudden respiratory symptoms. But what about the impact on those who will need to continue to be isolated at home? Can children have the virus without showing symptoms? Yes. Can they therefore be spreaders of C-19? Yes they can, and because we have not been doing effective testing, contact tracing and isolation, this could be problematic. If the government’s testing and contract tracing system, run by Deloitte’s and supported by the national app is up and running by early June, will this make it safer? Probably, but there is great cynicism in the world of Public Health that this approach is desirable. As stated above, the tried and tested model of this all being run by the Directors of Public Health and their teams in each geography, supported by local GPs is deemed to be much more effective. Local knowledge and guidance would, I believe, give local teachers much more confidence with more readily available advice where needed. Should staff be wearing face masks? There is varying advice on this. Our local authority currently says no, but Prof Trish Greenhalgh from Oxford University advises that they should, on the basis that face masks reduce the spread of C19 and can perhaps offer some protection for the wearer also.

What are the risks of not opening the schools? Well, we know that 10% of all children in the UK (and this is not dependent on social class, so kids at private schools are at just as much risk) are likely to be suffering from 4 Adverse Childhood Experiences. The impact of this kind of trauma on them can be absolutely huge in the long term and schools and key relationships with teachers/TAs can be significantly protective factors. Schools also play a very important role in tackling food poverty and ensuring many children get 2 or even 3 good meals. So Steve Chalke is right that not opening schools could appear like a middle-class luxury. But will putting kids who need security and love, into an alien situation with facemarks, social distancing and a very different kind of day to usual, actually compound the sense of trauma? We don’t know yet, but we will need to watch this carefully, if and when the schools do go back. Perhaps headteachers could prioritise those children most at risk, over the 4 and 5 year olds, who it will be very hard to keep socially distanced. What I will say though, is that headteachers are not the ‘bad guys’ here. I don’t know one headteacher who doesn’t want anything except the best for the children in their school and genuinely wants to be able to have them back.

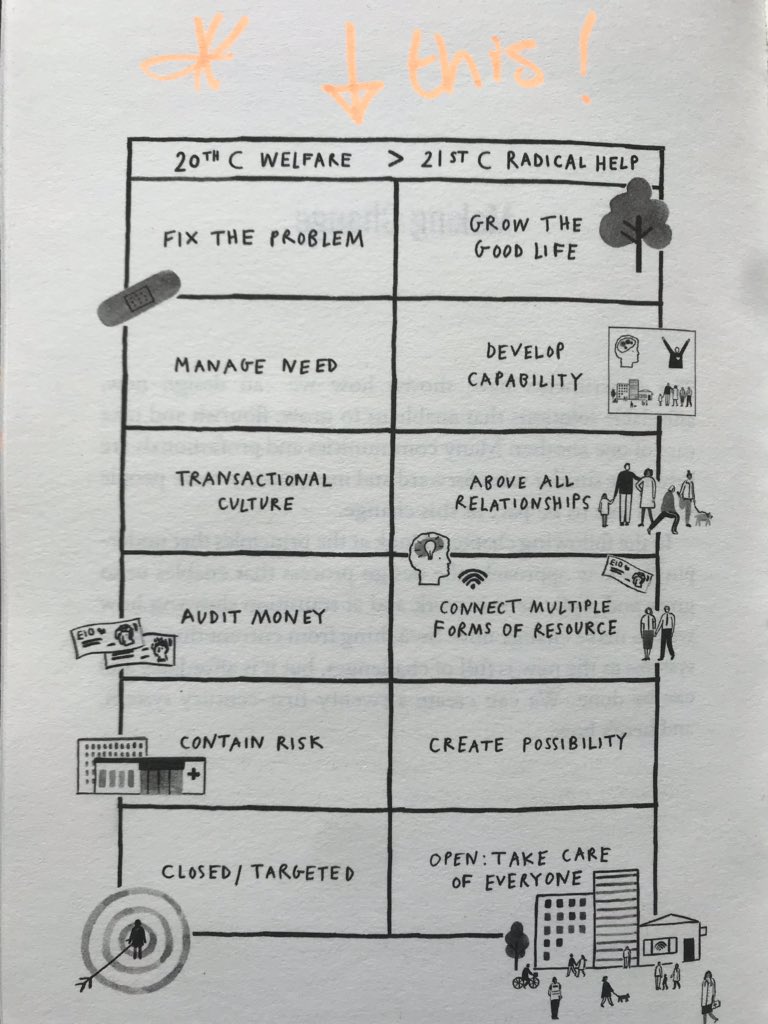

Without effective or sufficient testing and contact tracing, we do put ourselves at risk of an early second peak. This is a risk – are we prepared to take it in the face of what we know about the rise in domestic violence, childhood trauma and growing mental health issues? Will 6 weeks back at school before the summer really be worth it? Should we mitigate the risk by not opening and ensure that we are more sure of the necessary processes being in place first? The decision ultimately belongs with each head teacher with support from their governing body, as to whether or not to open on June 1st. It is dependent on what is practicable in their given location and with the staff and facilities they have at their disposal. The government guidance is difficult to implement in many settings. So let us be kind to each other. Let’s be honest about where we are and just how complex this is. For those who want to dip their toe in and give it a go, we must ensure that guidance is followed as closely as possible, especially hand washing, cleaning of surfaces and physical distancing, where practical. For those who decide to wait, fair enough. But whatever happens, let us be determined to build an education system that is fit for the future. Let us rebuild education based on love and kindness and let’s be brave enough to redesign the curriculum around the needs of humanity and the ecology.

So, in summary:

- These are my own opinions

- Is it safe for children and teachers to go back to school? Possibly, but without satisfactory testing, contact tracing and isolation in place and with growing evidence that this will not be adequate by June 1st and with an inaccurate R number due to an incomplete list of symptoms for testing people, there is a risk to the wider public that we could enter an early second peak. It would be prudent for the government to seriously reconsider their centralised approach to this, when empowering local government and public health teams to lead this process will be far more effective. It may be safe for children to begin to return to school (I think), but maybe not for wider society.

- At what point then, would it be safe for schools to reopen? Perhaps once we are more sure that the protective public health systems we need to be fully operational are in place and running effectively. But we do need to return to school soon, so we need to find a way through – that way is unlikely to come through centralised command and control but will rather require a participatory and inclusive approach. So the answer is maybe but maybe not quite yet – better to get it right than to risk getting it horribly wrong by rushing it.

- If schools choose to reopen, due to the concerns about issues like trauma, mental health and hunger, what are the issues they need to consider? The current government advice on social distancing is impractical and schools may need to look for community partners, who may be willing to help with other local premises (e.g. churches, mosques and local halls) to enable this to be possible. They will also need to ensure good hand washing, cleaning of surfaces and consider what they want to do about face masks AND we need to re-emphasise this advice to the wider public. Schools will also need to think about how they staff the recommended ‘bubbles’ and whether or not they will need community DBS-checked volunteers to help out. On top of this they will need to consider who they initially prioritise how they support the emotional and mental health of our children, young people and staff in a very different kind of setting. And they will need to remain inclusive of those children and young-people who cannot return to school due to having underlying health conditions themselves or in their households.

- Whatever happens, let’s ensure a more participatory and inclusive conversation about the path ahead of us. Schools need to be involved in the process.

- Let us also have a wider conversation about the kind of education system we need for the future. Lots of good thinking on this already across the UK and some podcasts coming soon.