Applying a Population Health Approach to Adverse Childhood Experiences

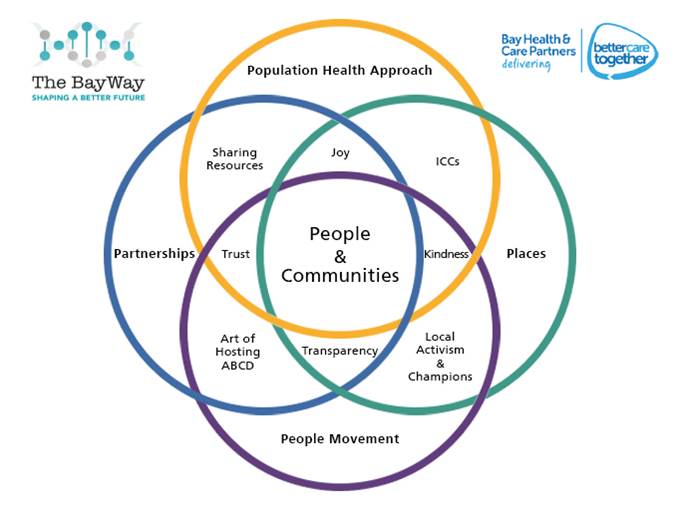

Adverse Childhood Experiences are one of our most important Population Health issues due to their long lasting impact on the physical, mental and emotional health and wellbeing of a person and indeed the wider community. It is therefore really important that we apply a ‘population health’ approach in our thinking about them so that we can begin to transform the future together. This is an area of great complexity with several contributing factors and will take significant partnership across all levels of government, public bodies, organisations and communities to bring about a lasting change. There are things we can do immediately and things that will take longer, but with a growing awareness of just what a significant impact ACEs are having on our society, we must act together to do something now. Here in Morecambe Bay, we have developed a way of thinking about Population Health in what we call our ‘Pentagon Approach’. It can be applied to ACEs as a helpful framework for thinking about how we begin to turn this tide and cut out this cancer from our society and feeds into the already great work being done across Lancashire and South Cumbria, lead by Dr Arif Rajpura and Dr Helen Lowey, who have spearheaded so much!

Prevent

When we examine the list of things that pertain to ACEs (see previous https://reimagininghealth.com/facing-our-past-finding-a-better-future/ blog), it is easy to feel overwhelmed and put it into the ‘too hard to do’ box. This is no longer an option for us. We must begin to think radically at a societal level about how we prevent ACEs from happening in the first place (recognising that some ACEs are more possible to prevent than others). Prevention will entail a mixture of community grass-roots initiatives, changes in policy and a re-prioritisation of commissioning decisions for us to make a difference together. Here are some practical suggestions:

- The first step is most certainly to break down the taboo of the subject and continue to raise awareness of just how common ACEs are and how utterly devastating they are for human flourishing. ACE aware training is therefore vital as part of all statutory safeguarding training.

- We have to tackle health inequality and inequality in our society. ACEs, although common across the social spectrum are more common in areas of poverty. Although we now have more people in work, many people are not being paid a living wage, work settings are not necessarily healthy and child poverty has actually increased over the last 5 years in our most deprived areas https://www.jrf.org.uk/blog/poverty-taking-hold-families-what-can-we-do.

- Parenting Classes should be introduced at High School in Personal and Social Education Classes to help the next generation think about what it would mean to be a good parent. These should also form an important part of antenatal and post-natal care, with further classes available in the community for each stage of a child’s development. Extra support is needed for the parents of children with special developmental or educational needs due to the increased stress levels involved.

- There needs to be a particular focus on fatherhood and encouraging young men to think about what it means to father children. Recent papers have demonstrated just how important the role of a father can be (positive or negative) in a child’s life and it is not acceptable for the parenting role to fall solely to the mother. www.eani.org.uk/_resources/assets/attachment/full/0/55028.pdf

- We have much to learn from the ‘recovery community’ about how to work effectively with families caught in cycles of addiction from alcohol or drugs. Finding a more positive approach to keeping families together whilst helping those caught in addictive behaviour to take responsibility for their parenting or learn more positive styles of parenting, whilst helping to build support and resilience for the children involved is really important.

- We must ensure that our social services are adequately funded and that there is continuity and consistency in the people working with any given family, especially around the area of mental health. Relationships are absolutely key in bringing supportive change and we must breathe this back into our welfare state.

- Hilary Cottam writes powerfully in her book, Radical Help that we must foster the capabilities of local communities, making local connections and “above all, relationships”. As Cottam states, “The welfare state is incapable of ‘fixing’ this, but it has an important role to play. It can catch us when we fall, but it cannot give us flight.

- Sex education in schools needs to be more open and honest about the realities of paedophilia and developing sexual desire. Elizabeth Letourneau argues powerfully that paedophilia is preventable not inevitable. We must break open this taboo and start talking to our teenagers about it. (https://www.tedmed.com/talks/show?id=620399&utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss)

Detect

If we want to make a real difference to ACEs and their impact on society, we need to be willing to talk about them. We can’t detect something we’re not looking for. Therefore as our awareness levels rise of the pandemic reality of ACEs, we need to develop ways of asking questions that will enable children or people to ‘tell their story’ and uncover things which may be happening to them or may have happened to them which may be deeply painful, or of which they may have memories which are difficult to access. Again, our approach needs to be multi-level across many areas of expertise. We need to be willing to think the unthinkable and create environments in which children can talk about their reality. For children in particular, this may need to involve the use of play or art therapy.

- Whole school culture change is vital, with a high level of prioritisation from the school leadership team is needed to ensure this becomes everybody’s business.

- School teachers and teaching assistants need to be given specific training, as part of their ‘safeguarding’ development about how to recognise when a child may be experiencing an ACE and how to enable them to talk about it in a non-coercive, non-judgmental way.

- Police and social services need training in recognising the signs of ACEs in any home they go into. For example, in the case of a drug-related death, how much consideration is currently given to the children of the family involved, and how much information is shared with the child’s school so that a proactive, pastoral approach can be taken. There are good examples around England where this is now beginning to happen. (http://www.eelga.gov.uk/documents/conferences/2017/20%20march%202017%20safer%20communities/barbara_paterson_ppt.pdf)

For adults, we need to recognise where ACEs might have played a part in a person’s physical or mental health condition (remember the stark statistics in the previous blog on this subject). Therefore we need to develop tools and techniques to help people open up about their story and perhaps for clinicians to learn how to take a ‘trauma history’.

- Clinical staff working in healthcare need to be given REACh training (routine enquiry about adverse childhood experiences – Prof Warren Larkin) as part of their ongoing Continuous Professional Development (CPD). In busy clinics it is easier to focus on the symptoms a person has, rather than do a deeper dive into what might be the cause of the symptoms being experienced. A wise man once said to me, “You have to deal with the root and not the fruit”. Learning to ask open questions like “tell me a bit about what has happened to you” rather than “what is wrong with you”, can open up the opportunity for people to share difficult things about their childhood, which may be profoundly affecting their physical or mental health well into adulthood. There is a concern that opening up such a conversation might lead to much more work on the part of the clinician, but studies have shown that simply by giving someone space to talk about ACEs they have experienced, they will subsequently reduce their use of GPs by over 30% and their use of the ED by 11%.

- We can ask each other. This issue is too far reaching to be left to professionals. If simply by talking about our past experiences, we can realise that we are not alone, we are not freaks and we do not have to become ‘abusers’ ourselves, then we can learn to help to heal one another in society. Caring enough to have a cup of tea with a friend and really learn about each other’s life story can be an utterly healing and transformational experience. When we are listened to by someone with kind and fascinated, compassionate eye, we can find incredible healing and restoration. One very helpful process, ned by the ‘more to life’ team is about processing life-shocks. Sophie Sabbage has written a really helpful book on this, called ‘Lifeshocks’).

Protect

When a child is caught in a situation in which they are experiencing one or more ACE, we must be vigilant and act on their behalf to intervene and bring them and their family help. When an adult has disclosed that they have been through one or more ACE as a child, we must enable them to be able to process this and not let them feel any sense of shame or judgement.

- We need to ensure school teachers are more naturally prone to thinking that ‘naughty’ or ‘difficult’ children are actually highly likely to be in a state of hyper vigilance due to stressful things they are experiencing at home. Expecting them to ‘focus, behave and get on with it’, is not only unrealistic, it’s actually unkind. Equally, children who are incredibly shy and easily go unnoticed must not be ignored. Simply recognising that kids might be having a really hard time, giving them space to talk about it with someone skilled, teaching them some resilience and finding a way to work with their parents/carers via the school nurse/social worker could make a lifetime of difference. It is far more important that our kids leave school knowing they are loved, with a real sense of self-esteem and belonging than with good SATS scores or GCSEs. The academic stuff can come later if necessary and we need to get far better at accepting this. A child’s health and wellbeing carries far more importance than any academic outcomes and Ofsted needs to find a way to recognise this officially. In other words, we need to create compassionate schools and try to ensure that school itself does not become an adverse childhood experience for those already living in the midst of trauma.

- In North Lancashire, we have created a hub and spoke model to enable schools to be supportive to one another and offer advice when complex safeguarding issues are arising. So, when a teacher knows that they need to get a child some help, they can access timely advice with a real sense of support as they act to ensure a child is safe. These hubs and spokes need to be properly connected to a multidisciplinary team, who can help them act in accordance with best safeguarding practice. This MDT needs to incorporate the police, social services, the local health centre (for whichever member of staff is most appropriate) and the child and adolescent mental health team.

- For adults who disclose that they have experienced an ACE, appropriate initial follow up should be offered and a suicide risk assessment should be carried out.

Manage

For children/Young People, the management will depend on the age of the child and must be tailored according to a) the level of risk involved and b) the needs of the child/young person involved. Some of the options include:

- In severe cases the child/YP must be removed from the dangerous situation and brought under the care of the state, until it is clear who would be the best person to look after the child/YP

- Adopting the whole family into a fostering scenario, to help the parents learn appropriate skills whilst keeping the family together, where possible.

- EmBRACE (Sue Irwin) training for safeguarding leads and head teachers in each school, enabling children/YP to learn emotional resilience in the context of difficult circumstances.

- Art/play therapy to enable the child to process the difficulties they have been facing.

For adults who disclose that they have experienced ACEs, many will find that simply by talking about them, they are able to process the trauma and find significant healing in this process alone. However, some will need more help, depending on the physical or mental health sequelae of the trauma experienced. Thus may include:

- Psychological support in dealing with the physical symptoms of trauma

- Targeted psychological therapies, e.g. CBT or EMDR to help with the consequences of things like PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder).

- Medication to help alleviate what can be debilitating symptoms, e.g. anti-depressants

- Targeted lifestyle changes around relaxation, sleep, eating well and being active

- Help with any addictive behaviours, e.g. alcohol, drugs, pornography, food

Recover

Again, this will follow on from whatever management is needed in the ‘healing phase’ to enable more long term recovery. There are many things which may be needed, especially as the process of recovery is not always straightforward. These may include:

- The 12 step programme, or something similar in walking free from any addiction.

- Revisiting psychological or other therapeutic support

- Walking through a process of forgiveness (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQ-j7NuhDEY&list=PLEWM0B0r7I-BXq6_wO4sL0qIwzTWwn_vx&index=9&t=0s, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EtexaUCBl5k&list=PLEWM0B0r7I-BXq6_wO4sL0qIwzTWwn_vx&index=9)

- We may need to help children go through development phases, which they have missed, at a later stage than usual, e.g. some children will need much more holding, cuddling and eye contact if they have been victims of significant neglect.

- Compassionate school environments to help children and young people catch-up on any work missed, in a way they can cope with and reintegrate into the classroom setting where possible, but with head teacher discretion around sitting exams.

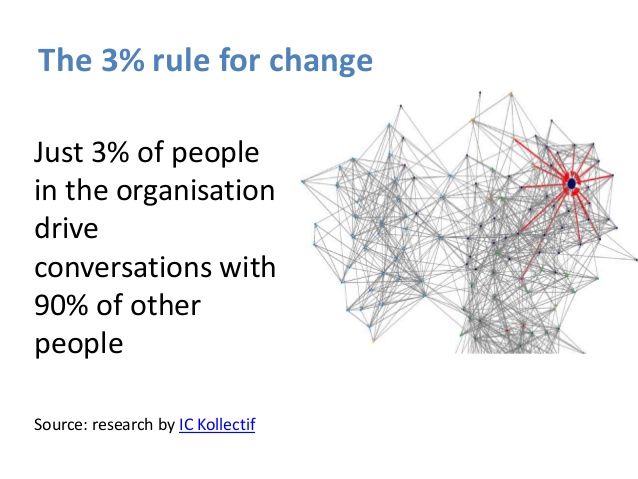

To complete the cycle, those who have walked through a journey of recovery are then able, if they would like to, to help others and form part of the growing network of people involved in this holistic approach to how we tackle ACEs in our society.

Hopefully this is a helpful framework to think as widely and holistically as possible. There is much great work going on around ACEs now and we must develop a community of learning and practice as we look to transform society together. We can’t do this alone, but together we can!