There is a ‘kairos moment’ available to us to reimagine how we think about health and care, here in the UK and indeed globally. It’s true that COVID-19 is going to continue to take our attention and shape our health and care services in a particular way for many months ahead. But some have been talking about COVID-19 as an apocalyptic event. The word apocalypse literally means “to lift the veil” i.e. it causes us to see what is behind the facades. Therefore, if we are living through some kind of apocalypse, let us see with new and clear eyes what it is showing to us. If the facades are down – what is it that we are now seeing in plain sight, which may have been previously hidden from us and what are we going to change as a result? COVID-19 is exposing for us, yet again, what Michael Marmot has been telling us for years, that poor health affects our economically poorer communities and poverty kills. We cannot ignore the greater impact felt by those of our BAME citizens and what this speaks to us. We see the burnout of NHS and Social Care Staff highlighted by Prof Michael West, even more clearly, just how valued they are by the public and the unsustainable nature of their workload, caused by long hours, high demands and under resource. So what kind of health and care service does the future need?

in the UK and indeed globally. It’s true that COVID-19 is going to continue to take our attention and shape our health and care services in a particular way for many months ahead. But some have been talking about COVID-19 as an apocalyptic event. The word apocalypse literally means “to lift the veil” i.e. it causes us to see what is behind the facades. Therefore, if we are living through some kind of apocalypse, let us see with new and clear eyes what it is showing to us. If the facades are down – what is it that we are now seeing in plain sight, which may have been previously hidden from us and what are we going to change as a result? COVID-19 is exposing for us, yet again, what Michael Marmot has been telling us for years, that poor health affects our economically poorer communities and poverty kills. We cannot ignore the greater impact felt by those of our BAME citizens and what this speaks to us. We see the burnout of NHS and Social Care Staff highlighted by Prof Michael West, even more clearly, just how valued they are by the public and the unsustainable nature of their workload, caused by long hours, high demands and under resource. So what kind of health and care service does the future need?

In the UK, we have a health system that responds brilliantly to crisis (in the most part). We’re by no means perfect, but we do acute care really rather well. But overall, although the WHO rates our health system as one of the best in the world, our current system approach is not tackling health inequality, it is not coping with the huge mental health crisis and it is floundering with the cuts to local government and our ability to work in an upstream preventative way. Meanwhile, our over-busy, over-hurried workforce don’t have the time to really care for themselves (thus huge levels of burnout and low staff morale) or bring genuine, lasting therapeutic healing to our communities. I cannot tell you how many NHS and Social care professionals I see in my clinic at the point of despair. I know of whole social care teams who have cried under their desks and vomited into the bins in their offices because of the untold pressure they feel under to manage hugely complex and unsafe portfolios. Now is the moment when we have to grasp the nettle and accept that we can’t go back there. I don’t want to. My friends and colleagues don’t want to and truly, we simply can’t afford to.

Our health and care system tends to focus on short-term (political) gains and quick, demonstrable change, rather than the bigger ticket items around genuine population health. Sometimes we just change things for the sake of changing things but without a focus on what it is that we really want to see change. It’s exhausting. We can quickly build several new Nightingale Hospitals (which thankfully we haven’t needed), but we haven’t been able to ensure wide-scale testing, contact tracing and appropriate isolation. We can easily promise to build 40 new hospitals and feel excited by this prospect, but we have seen a decreasing life expectancy in women from our economically most deprived communities and a worsening gap in life expectancy. We need a health and care system which creates health and wellbeing in our communities, while maintaining the ability to respond to crises.

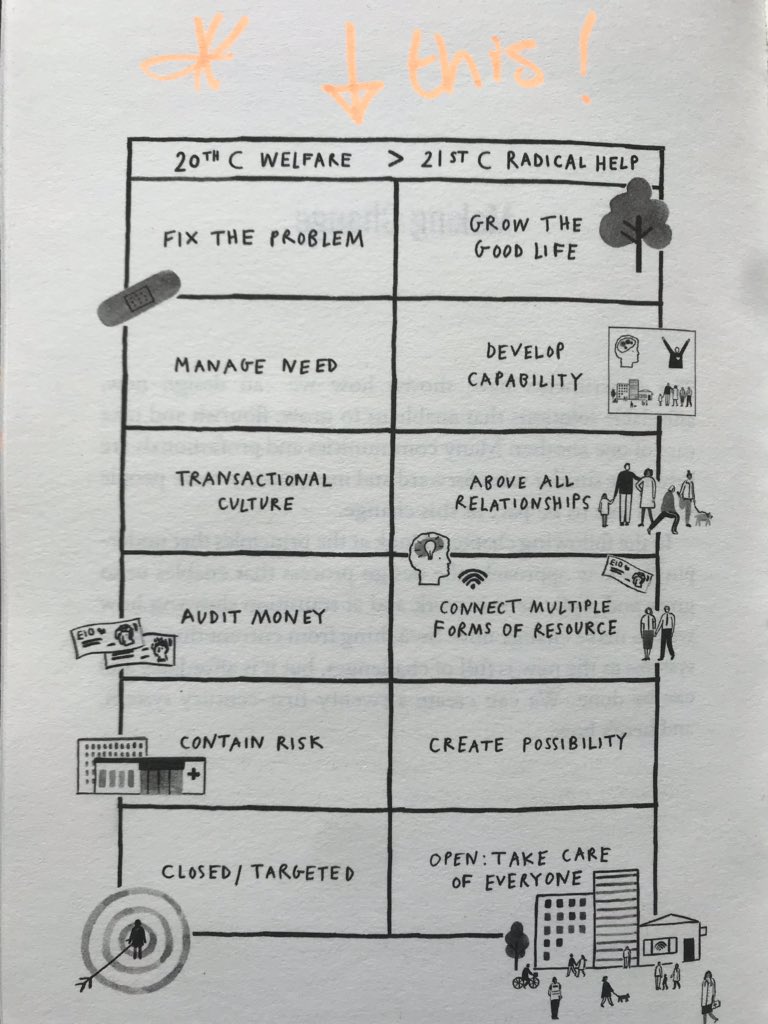

My friend, Hilary Cottam has written in her book ‘Radical Help’ abut the reimagining of the Welfare State for the 21st Century, with some superb examples of what can be made possible, especially within the realm of Social Care, for all age groups. Where this was applied most widely in Wigan, under the beautifully humble, kind, collaborative and inclusive leadership of then Chief Executive, Prof Donna Hall, the results were and continue to be staggering. One of the devastating parts of Hilary’s book is to read her chapter on experiments in the NHS. They were hugely successful, saved money and delivered better care, but when push came to shove, commissioners couldn’t extract funding from where it was to invest in the ‘brave new world’. It would be possible to conclude that the kind of transformation we need to see in the NHS is not currently possible – partly related to culture and partly because of centrally driven targets, which make brave financial choices hard to make with associated adverse political backlash. But I remain optimistic! As we look towards a desperately needed, more integrated health and care system, I believe if we applied Hilary’s 6 core principles with some audacity, we might see some amazing things occur in our communities.

My friend, Hilary Cottam has written in her book ‘Radical Help’ abut the reimagining of the Welfare State for the 21st Century, with some superb examples of what can be made possible, especially within the realm of Social Care, for all age groups. Where this was applied most widely in Wigan, under the beautifully humble, kind, collaborative and inclusive leadership of then Chief Executive, Prof Donna Hall, the results were and continue to be staggering. One of the devastating parts of Hilary’s book is to read her chapter on experiments in the NHS. They were hugely successful, saved money and delivered better care, but when push came to shove, commissioners couldn’t extract funding from where it was to invest in the ‘brave new world’. It would be possible to conclude that the kind of transformation we need to see in the NHS is not currently possible – partly related to culture and partly because of centrally driven targets, which make brave financial choices hard to make with associated adverse political backlash. But I remain optimistic! As we look towards a desperately needed, more integrated health and care system, I believe if we applied Hilary’s 6 core principles with some audacity, we might see some amazing things occur in our communities.

For me, the change must begin from the inside – if we do not get our culture right (and we still have some significant issues around bullying, discrimination, staff well-being and poor citizen care) then it won’t matter what we do structurally or how we reorganise ourselves. If you haven’t seen my TEDx talk about how we create the kind of culture that allows us to do this, then you might find it helpful to watch it here.

Hilary’s six steps give us a really good platform from which to reimagine and build a health and care system fit for the future that is calling us:

Grow the Good Life!

We know that COVID has primarily affected our more economically poor areas with a significantly higher mortality rate. This is not news, but perhaps we see it more starkly in the light of this current pandemic. Michael Marmot has been telling us this for decades but his recent report (link above) highlights for us the decline in health outcomes and worsening health inequalities, since 2010. Firstly, we must recognise that the good life is not supposed to be only for the rich and nor does money necessarily lead to a ‘good life’. The good life is for everyone, everywhere. Secondly, we must accept that the good life is something which is not shaped by the powerful on behalf of communities. It is grown, fostered and tended by communities themselves, who own the mandate that ‘nothing about us without us, is for us’. Thirdly, we must therefore stop taking a reactionary approach to health and care and create wellness in and with our communities, determined to break down age-old health inequalities, tackle poverty, poor housing and climate change. We must accept that we cannot fix the problem and there will be no real health for our communities unless we cultivate the space for the good life to grow. A good place to start would be with a Universal Basic Income. It also means working across the public and business sectors to think about how we can be good employers and create the kind of jobs that the world really needs in the 21st Century – I’m excited to see that conversation alive and well, here in Morecambe Bay, particularly in Barrow-in-Furness and in Lancaster and Morecambe. It means ensuring that everyone has a home and access to good and clean transport. The good life must include a good start in life (and reverse the tide of childhood trauma), good opportunities to learn and develop (within a reset learning/education sector), good community, good work, good ageing and a good death. The good life enables us to be a good citizen, locally and globally and therefore the good life leads to a regenerated ecology. The good life must also include a good safety net if life falls apart or hard times come and really good care for those who live with the reality of chronic ill (physical and/or mental) health. The good life ensures that the elderly are honoured and cared for. It cannot be stated strongly enough that if we do not grow the good life then we will continue with the same old issues and the ongoing inequalities for generations to come. Health is primarily an economic issue and so all economic policies and choices show us who and what we value. Where do we need to shift our priorities and our resources in order to grow the good life together? Let us see beneath and behind the facades exposed in this moment and be determined that together we must co-create a much kinder and more compassionate society. There are so many economists (e.g. Mariana Mazzucato on how we create value, Kate Raworth on an Economics worthy of the 21st Century, Katherine Trebeck on why we need a Wellbeing Economy) doing great work on this. Why aren’t we listening to them more? Perhaps we are. 80% of people in the UK now want health and wellbeing to be prioritised over Economic Growth!

ensures that the elderly are honoured and cared for. It cannot be stated strongly enough that if we do not grow the good life then we will continue with the same old issues and the ongoing inequalities for generations to come. Health is primarily an economic issue and so all economic policies and choices show us who and what we value. Where do we need to shift our priorities and our resources in order to grow the good life together? Let us see beneath and behind the facades exposed in this moment and be determined that together we must co-create a much kinder and more compassionate society. There are so many economists (e.g. Mariana Mazzucato on how we create value, Kate Raworth on an Economics worthy of the 21st Century, Katherine Trebeck on why we need a Wellbeing Economy) doing great work on this. Why aren’t we listening to them more? Perhaps we are. 80% of people in the UK now want health and wellbeing to be prioritised over Economic Growth!

Develop Capability

Cormac Russell, the fantastic advocate of ABCD and all round champion of community power recently said this:

“The truth is, ‘the needed’ need ‘the needy’ more than ‘the needy’ need ‘the needed’. Society perpetuates the opposite story; because there’s an entire segment of the economy tied up in commodifying human needs. It’s a soft form of colonisation. That’s what needs to change.”

Perhaps, if the NHS and/or Social Care were a personality type on the Enneagram, it would be Type 2, or in other words it has a need to be needed. Perhaps we are the ones afraid of removing the ‘medical model’ and trusting people and communities to figure it out themselves – time, as we often say is a great diagnostic tool and a great healer. Many little niggles and issues often sort themselves out on their own, or with a good listening ear, or a change in diet, or some other remedy. What if, instead of trying to manage unmanageable need (at least a portion of which we have created ourselves by the very way we have designed our systems and through the narratives we tell our communities), we develop real capability in and with our communities? We have been interested in the world of General Practice how many people haven’t been in contact with us during COVID-19. I think the reasons for this in some ways are obvious (people were told to stay at home and so they did just that, and they wanted to protect the NHS, so they didn’t want to bother us) but in others are perhaps more complex and not necessarily altogether good – meaning we are seeing far few people with potential symptoms of more worrying conditions, like suspected cancers of various sorts. How do we design a system that starts with the good life, enhances community well-being, enables better collaborative care within and from communities themselves, whilst being able to respond to real need?

Perhaps, if the NHS and/or Social Care were a personality type on the Enneagram, it would be Type 2, or in other words it has a need to be needed. Perhaps we are the ones afraid of removing the ‘medical model’ and trusting people and communities to figure it out themselves – time, as we often say is a great diagnostic tool and a great healer. Many little niggles and issues often sort themselves out on their own, or with a good listening ear, or a change in diet, or some other remedy. What if, instead of trying to manage unmanageable need (at least a portion of which we have created ourselves by the very way we have designed our systems and through the narratives we tell our communities), we develop real capability in and with our communities? We have been interested in the world of General Practice how many people haven’t been in contact with us during COVID-19. I think the reasons for this in some ways are obvious (people were told to stay at home and so they did just that, and they wanted to protect the NHS, so they didn’t want to bother us) but in others are perhaps more complex and not necessarily altogether good – meaning we are seeing far few people with potential symptoms of more worrying conditions, like suspected cancers of various sorts. How do we design a system that starts with the good life, enhances community well-being, enables better collaborative care within and from communities themselves, whilst being able to respond to real need?

Surely people who live with various health conditions, or who have social needs should be in the driving seat when it comes to understanding their own condition or situation, recognising what their options are and deciding how to manage the care they receive. We must take a less paternalist approach to health and care and focus much more on coaching, empowerment and collaboration. Services will only really work for the people who need them, when they are co-designed by them. We will find this is much more cost effective, wholly more satisfying for all involved and will create a virtuous circle in creating the good life. Social prescribing goes some of the way, but is still way too prescriptive. This is about taking a step back and building understanding and creating more capability to live well in our communities, by focusing on a building on the strengths which are already there. We will only do this if we dare enough to really listen, putting aside what we presume we know and start a new conversation with our communities about what we really need together. We can do this in multiple ways, making the best use of available technology.

Above All Relationships

I believe relationship is pretty much at the heart of everything meaningful. If we’re really going to create the kind of health and care system that is fit for the 21st century, it’s not that we need to be less professional, it’s that we need to become more relational, step out from behind our lanyards and turn up as human beings first and foremost. When we really listen to the communities we serve we discover what a wasteful disservice we provide to the public in our current transactional approach. Yes we tick the boxes that keep our paymasters happy and fulfil our stringent KPIs, but in doing so, we spectacularly miss the point. Hilary’s chapter on the power of relationships in family social care is particularly poignant on this issue. If we plot the kind of interventions we make with perhaps the most troubled members of our community from a social care, mental health, policing and physical health perspective; we find that we make hundreds of contacts, spend an inordinate amount of money and see very little change for the fruit of our labour. What a waste! But when we ask these families what they really need, what their hopes and dreams are and how we might work with them to make this possible – yes there are bumps along the way, but we find with smaller and less expensive teams, we can achieve far more, because relationships are consistent, build trust and create the environment needed for real support and transformation. Why would we persist with a model that is outdated and doesn’t work?! Why are we afraid to work differently? We have to stop doing to and be together with. I believe Primary Care Networks create the kind of framework that begin to make this more possible. I think that if we see health visitors, school nurses, physios, SLTs, OTs, mental health teams and social workers integrated into these teams, we will see far more joined-up, cost-effective and relational care in and with our communities. In some ways, it doesn’t even matter who the ’employer’ is as long as we allow teams to work in a really inter-dependent way.

I believe relationship is pretty much at the heart of everything meaningful. If we’re really going to create the kind of health and care system that is fit for the 21st century, it’s not that we need to be less professional, it’s that we need to become more relational, step out from behind our lanyards and turn up as human beings first and foremost. When we really listen to the communities we serve we discover what a wasteful disservice we provide to the public in our current transactional approach. Yes we tick the boxes that keep our paymasters happy and fulfil our stringent KPIs, but in doing so, we spectacularly miss the point. Hilary’s chapter on the power of relationships in family social care is particularly poignant on this issue. If we plot the kind of interventions we make with perhaps the most troubled members of our community from a social care, mental health, policing and physical health perspective; we find that we make hundreds of contacts, spend an inordinate amount of money and see very little change for the fruit of our labour. What a waste! But when we ask these families what they really need, what their hopes and dreams are and how we might work with them to make this possible – yes there are bumps along the way, but we find with smaller and less expensive teams, we can achieve far more, because relationships are consistent, build trust and create the environment needed for real support and transformation. Why would we persist with a model that is outdated and doesn’t work?! Why are we afraid to work differently? We have to stop doing to and be together with. I believe Primary Care Networks create the kind of framework that begin to make this more possible. I think that if we see health visitors, school nurses, physios, SLTs, OTs, mental health teams and social workers integrated into these teams, we will see far more joined-up, cost-effective and relational care in and with our communities. In some ways, it doesn’t even matter who the ’employer’ is as long as we allow teams to work in a really inter-dependent way.

Connect Multiple Forms of Resource

If we keep working in silos and continue to measure outcomes by single organisations, we will continue to fail the public, waste money and exhaust our staff. However, if we can agree on good outcomes in collaboration with the public we serve, join up our local budgets, share our public resources and empower our teams to work in a truly integrated and collaborative culture (as has been happening through this pandemic), then we can begin to make a real difference where it is needed and see lasting change in our communities. In Morecambe Bay, our integrated teams are working in this way but there is more for us to do and further for us to go. One of the things I have particularly loved about the Wigan vision is the core 3 things they ask for from all their staff – Be Positive (take pride in all that you do), Be Accountable (be responsible for making things better), Be Courageous (be open to doing things differently). Three simple principles have enabled a fresh mindset and a new way of working which is clearly seen across their public sector teams and in the community at large. If we don’t learn to co-commission in partnership with our communities and across our organisations, we will not shift the resources from where they are to where they need to be. It’s definitely easier in the context of a unitary authority, but not impossible, if the relationships are good, in other contexts also. However, as Donna Hall argues, commissioning often gets in the way and is a blocker, rather than an enabler of resources getting into the right places because of the rule books involved. Her experience and track-record are well worth listening to, uncomfortable though they may be for those of us who work in commissioning organisations. Scotland doesn’t commission health and care in the way England does – are there lessons to learn? I don’t know the answer, but it is worth a conversation. What we do need for sure is thinner walls, blurred boundaries, greater humility, genuine trust, greater collaboration, real honesty, mutual accountability and true integration between ‘sovereign’ public organisations and the overstretched and over-burdened community-voluntary sector and yes, the private sector (….this talk by economist Mariana Mazzucato on how innovation happens is really worth thinking about). If we allow ourselves to do this, we will be on the way to a welfare system that is much more sustainable and practical.

If we keep working in silos and continue to measure outcomes by single organisations, we will continue to fail the public, waste money and exhaust our staff. However, if we can agree on good outcomes in collaboration with the public we serve, join up our local budgets, share our public resources and empower our teams to work in a truly integrated and collaborative culture (as has been happening through this pandemic), then we can begin to make a real difference where it is needed and see lasting change in our communities. In Morecambe Bay, our integrated teams are working in this way but there is more for us to do and further for us to go. One of the things I have particularly loved about the Wigan vision is the core 3 things they ask for from all their staff – Be Positive (take pride in all that you do), Be Accountable (be responsible for making things better), Be Courageous (be open to doing things differently). Three simple principles have enabled a fresh mindset and a new way of working which is clearly seen across their public sector teams and in the community at large. If we don’t learn to co-commission in partnership with our communities and across our organisations, we will not shift the resources from where they are to where they need to be. It’s definitely easier in the context of a unitary authority, but not impossible, if the relationships are good, in other contexts also. However, as Donna Hall argues, commissioning often gets in the way and is a blocker, rather than an enabler of resources getting into the right places because of the rule books involved. Her experience and track-record are well worth listening to, uncomfortable though they may be for those of us who work in commissioning organisations. Scotland doesn’t commission health and care in the way England does – are there lessons to learn? I don’t know the answer, but it is worth a conversation. What we do need for sure is thinner walls, blurred boundaries, greater humility, genuine trust, greater collaboration, real honesty, mutual accountability and true integration between ‘sovereign’ public organisations and the overstretched and over-burdened community-voluntary sector and yes, the private sector (….this talk by economist Mariana Mazzucato on how innovation happens is really worth thinking about). If we allow ourselves to do this, we will be on the way to a welfare system that is much more sustainable and practical.

Create Possibility

Go on! Try it! It’s OK to fail! We’ve got your back! If it seems like a good idea, give it a try! These are things we need to say and hear much more in the world of health and care. Of course we need to be guided by evidence, but there are so many things we do every day, because ‘that’s the way we do it’, often governed by a culture of fear. What might be made possible if we garnered a real sense of innovation, creativity, bravery and experimentation instead? But this must not just be limited to our teams. What are the possibilities within our communities. How do they see things. What hopes do they carry? What opportunities have they noticed for more kindness, better integration, smarter working and improved services? Are the services we provide really meeting the need? If not, what is possible instead? There is an ancient proverb that says: “Hope deferred makes the heart sick, but hope coming is a tree of life…” I wonder how much of the current ‘sickness’ we see in our communities is because people have lost a sense of hope that they can be part of any meaningful change. Just imagine how much life, health and well-being would be released into local streets and neighbourhoods, simply by including people in the participatory experience of dreaming about and actually building a better future that is more socially just and environmentally sustainable. In Wigan – this looked like The Wigan Deal. We need to take a similar approach everywhere – it’s not about replicating it – it’s great to learn from best practice and implement it more widely. But it’s also important that we start from a place of deep listening and creating hope and possibility. Change happens best when it comes from local, grass roots communities, who love and take a greater sense of responsibilities for the areas which they know and love. If this is going to happen, we have to embrace the notion of New Power!

Open: Take Care of Everyone

Our target driven culture is the enemy of creating really good health and care in our communities. Small minded, measurement-obsessed, top-down, KPI-driven, bureaucratic micro-management is strangling the life out of our public services and preventing us from reimagining a welfare state, especially concerning social care that we so desperately need. We can no longer tolerate the staggering inequalities experienced by our poorest communities and therefore we can no longer contemplate continuing to accept the silo’d and misaligned (under) funding of local government, social care and the NHS. If we are going to have a society that is caring to everyone, no matter of their age, gender, genome or race, then we must be determined to build a system on the values we hold dear of love, hope, inclusivity, joy and kindness. There is no way that we can do this from within the system alone. But the future is calling us to explore new paths together and build a system with much more flexibility and adaptability. This is not outside of our gift, nor beyond our reach. We cannot do it alone. But if we let go of any fear of localism and wide participation, then together, with our communities, in the places where we live, we can create a society that truly cares.