NHS – we have a problem! This blog forms a hiatus in the middle of a 4 blog mini-series about what I call the four rings of leadership (in the context of healthcare). I have been musing on some statements made at the IHI conference in London, Quality 2017, and before I go any further, I want to take a pause to reflect on the notion of power. Helen Bevan says that the number one issue facing our health care system is the issue of power. I would suggest that unless we seriously reflect on power and how it manifests itself in our systems and in us as individuals, then we will never be able to co-create health and well-being in our society.

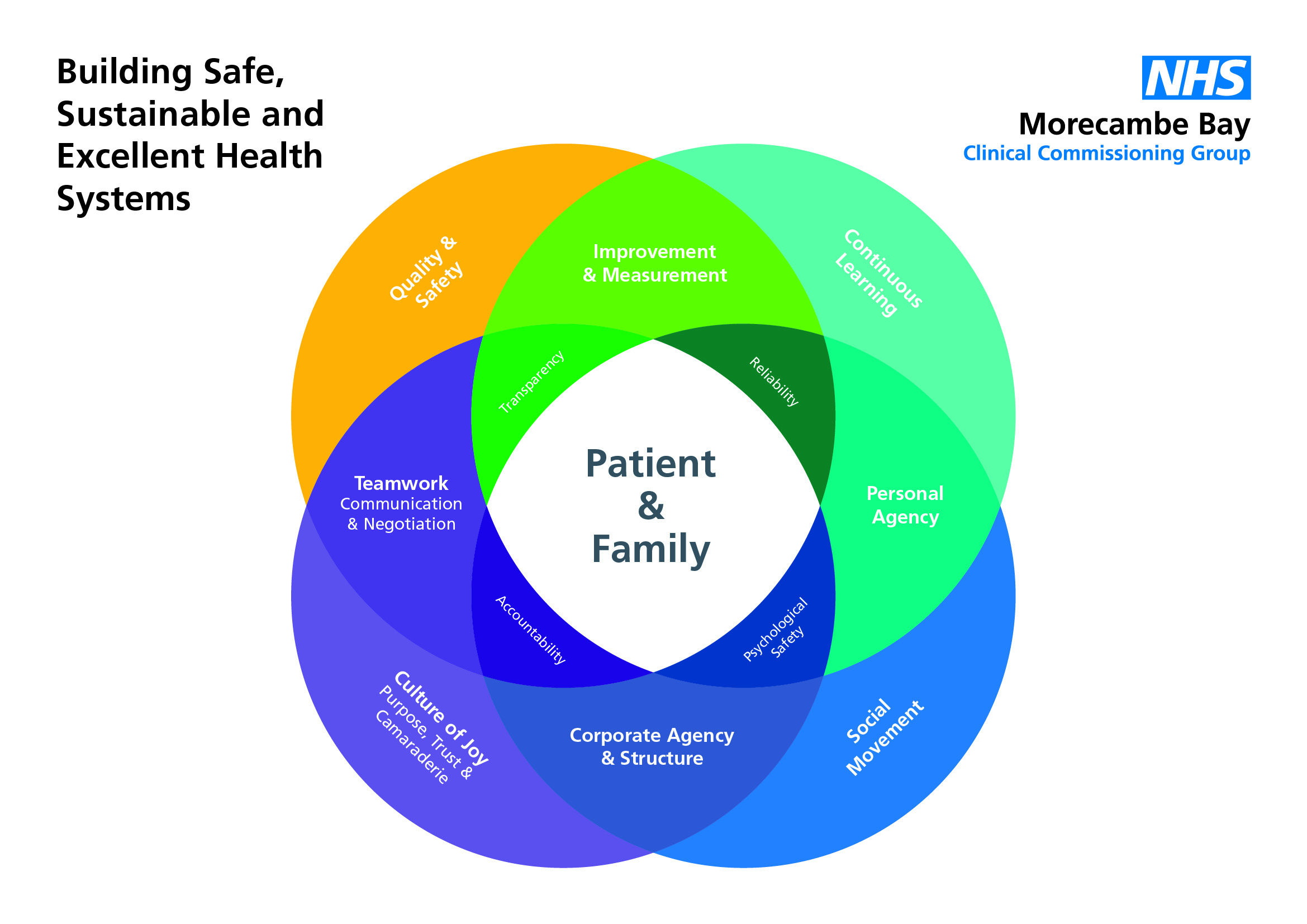

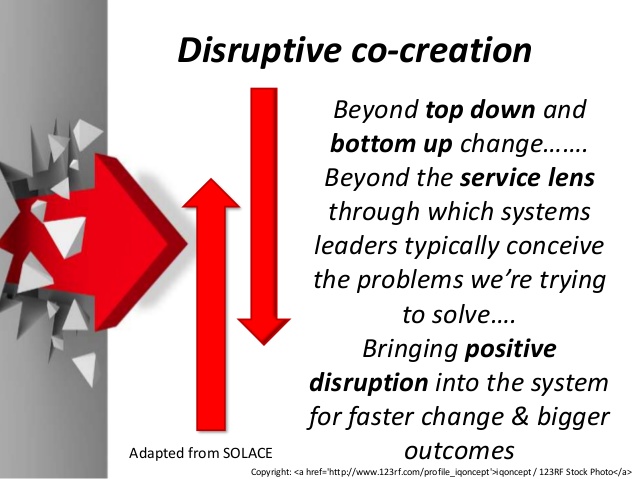

In my last blog, I mentioned an excellent talk that I heard Derek Feeley of IHI and Jason Leitch, the CMO of Scotland, give together about our need to “cede” power, if we are to build safe, high quality, economically sustainable health systems. They contend that we need to move from keeping power, to sharing power and then ceding power. To cede power, means to transfer/surrender/concede/allow or yield power to others. I do believe this is correct. I believe that true leadership is absolutely about being able to ’empty out’ positions or seats of power, so that all are empowered to effect positive change and build a society of positive peace. However, my contention is this: ceding power is not helpful unless we first deal with the very nature of power. Once we have dealt with its very substance can we truly cede it through our organisations and systems to bring increased well-being for all.

I have talked many times over the dinner table with my great friends Roger and Sue Mitchell about the nature of sovereignty and power. Sovereignty is a dominant theme within our political discourse at the moment, at a national and international level. It is worth reflecting that sovereignty (the right to self-govern) is utterly intertwined with our understanding of power, and we need to pull the two apart if we are ever to cede the kind of power that can transform the future. If we do not recognise (have a full awareness/deeply know) this, we will continue to inadvertently create hierarchical dominance and systems that become the antithesis of what they are created to be.

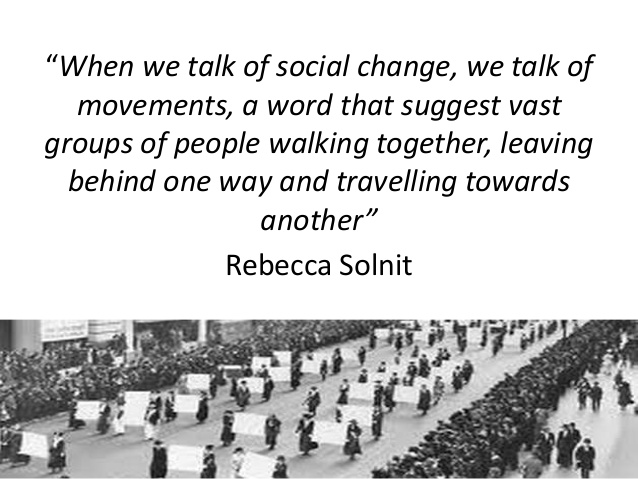

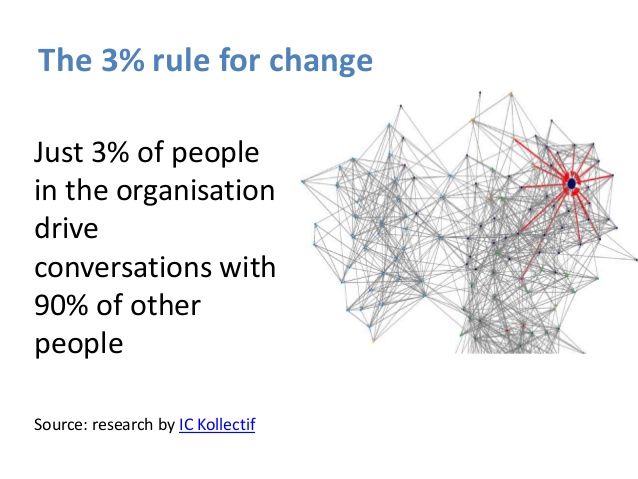

We see the issue of sovereign power at work every day in the NHS. We see it in terms of power edicts from on high, without understanding the local context or issues worked through in a relational way. We see it in the way these edicts are then outworked through leadership and management styles, which are very top-down and hierarchical in nature, eating up people like bread in the process – what Foucault calls “Biopower”. We see it in the way wards are managed and in the way GP surgeries are run. Sovereign power says “I’m in charge around here” and “we’re going to do things my way”. We see it in individuals who choose to practice autonomously without thinking about the wider implications on the system, prescribing however they would like to, without thinking about the cost implications. We see it in the attitude of some patients, when it becomes about “my rights” with an unbearable or unaffordable pressure put onto the system. If we multiply sovereign power, we simply end up with lots of kings and queens who defend their own castle, creating more barriers, walls and division in the process. Sovereign power is defunct and dangerous and it is this which is currently destroying our ecosystems and wider society. The “I did it my way” approach is rooted in self preservation and ambition and does nothing to help us build health and well-being in society. Sovereign power stands in the way the very social movements we need to see, because Sovereign power is based on fear.

We see the issue of sovereign power at work every day in the NHS. We see it in terms of power edicts from on high, without understanding the local context or issues worked through in a relational way. We see it in the way these edicts are then outworked through leadership and management styles, which are very top-down and hierarchical in nature, eating up people like bread in the process – what Foucault calls “Biopower”. We see it in the way wards are managed and in the way GP surgeries are run. Sovereign power says “I’m in charge around here” and “we’re going to do things my way”. We see it in individuals who choose to practice autonomously without thinking about the wider implications on the system, prescribing however they would like to, without thinking about the cost implications. We see it in the attitude of some patients, when it becomes about “my rights” with an unbearable or unaffordable pressure put onto the system. If we multiply sovereign power, we simply end up with lots of kings and queens who defend their own castle, creating more barriers, walls and division in the process. Sovereign power is defunct and dangerous and it is this which is currently destroying our ecosystems and wider society. The “I did it my way” approach is rooted in self preservation and ambition and does nothing to help us build health and well-being in society. Sovereign power stands in the way the very social movements we need to see, because Sovereign power is based on fear.

Sovereign power has its roots in certain streams of theology and philosophy which have in turn laid the foundation for a way of doing politics and economics based on the supremacy of the state and within that the individual. However, the damaging effects of this are seen on our environment and on community, with utterly staggering levels of inequality, injustice and damage to the world in which we live.

If we are to truly cede a power that is effectual in changing the world, then it is not enough to simply reconfigure (rearrange) it, or reconstitute it ( i.e. give it a new structure/share it). First of all, we must revoke it! In other words, we must look ‘Sovereign power’ straight in the eyes and reject it, cancelling it’s toxic effects on our own selves and on that of others. We must change our minds about it and embrace instead a wholly different kind of power. Sovereign power has not changed the world for the better so far, and I hold no hope of it doing so in the future. No, we don’t need Sovereign power and we certainly don’t want to cede it. Instead, we need kenotic power. Kenotic power is based in self-giving, others empowering love (Thomas Jay Oord). It empowers others, not to live like mini-dictators, but to also dance to a very different beat.

If we are to truly cede a power that is effectual in changing the world, then it is not enough to simply reconfigure (rearrange) it, or reconstitute it ( i.e. give it a new structure/share it). First of all, we must revoke it! In other words, we must look ‘Sovereign power’ straight in the eyes and reject it, cancelling it’s toxic effects on our own selves and on that of others. We must change our minds about it and embrace instead a wholly different kind of power. Sovereign power has not changed the world for the better so far, and I hold no hope of it doing so in the future. No, we don’t need Sovereign power and we certainly don’t want to cede it. Instead, we need kenotic power. Kenotic power is based in self-giving, others empowering love (Thomas Jay Oord). It empowers others, not to live like mini-dictators, but to also dance to a very different beat.

I used to play the card game bridge, with my Grandpa (he was an amazing man, who invented Fairy Liquid!). In bridge, to revoke something is to fail to follow suit, despite being able to do so. Kenotic power refuses to play the game of Sovereign power. It embraces an entirely different approach. And as many through the ages have found, this kind of power is truly costly, and can even cost you your career or life; but it is the only kind of power that truly changes the world for good. Jesus, Rosa Parks, Emmeline Pankhurst, Gandhi, MLK, Malala Yousafzai, Nelson Mandela, Florence Nightingale and Mother Theresa are just some, who have embraced this ‘self-giving, others empowering love-based power.’ This is the kind of power we need now. We need it in healthcare and in every other part of our society.

I used to play the card game bridge, with my Grandpa (he was an amazing man, who invented Fairy Liquid!). In bridge, to revoke something is to fail to follow suit, despite being able to do so. Kenotic power refuses to play the game of Sovereign power. It embraces an entirely different approach. And as many through the ages have found, this kind of power is truly costly, and can even cost you your career or life; but it is the only kind of power that truly changes the world for good. Jesus, Rosa Parks, Emmeline Pankhurst, Gandhi, MLK, Malala Yousafzai, Nelson Mandela, Florence Nightingale and Mother Theresa are just some, who have embraced this ‘self-giving, others empowering love-based power.’ This is the kind of power we need now. We need it in healthcare and in every other part of our society.

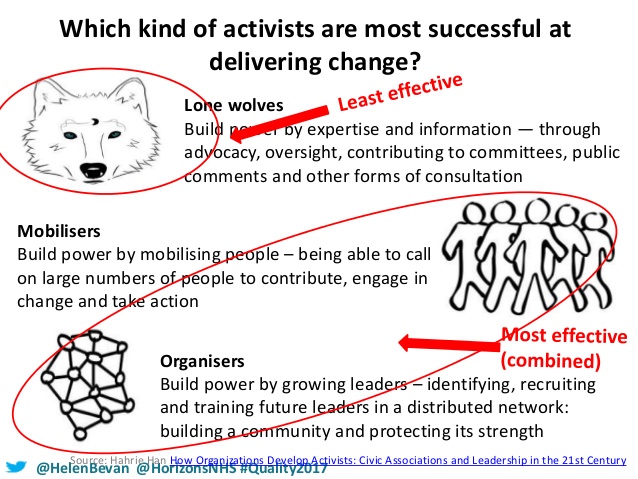

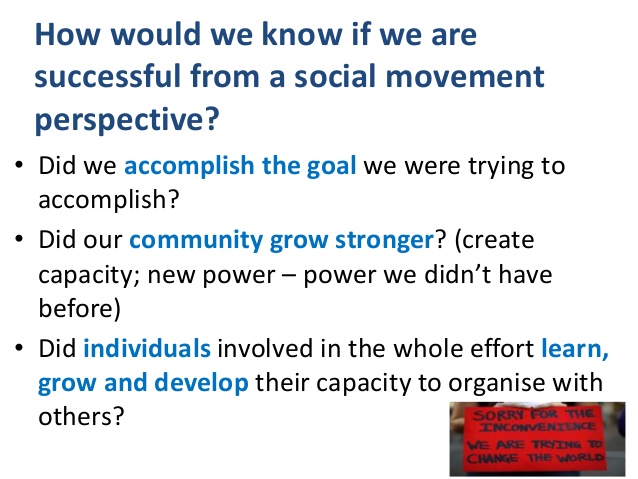

Kenotic power is vulnerable but it is not about being a door mat. It is like a beautiful martial art, in which we can say “I won’t fight you and you can’t knock me down, unless I let you” In other words, we lay down our rights and power freely, they are not taken from us by force. So, even when energetic attacks are launched against us, this kind of power allows us to move out of the way, allow the attack to pass through and then to come along side the person and help them see another point of view. Switching to this kind of power is far more creative, less combative and far more fruitful in creating a way ahead full of possibilities without the need for making enemies in the process. We must challenge the deep structural belief that our political and economic systems must be built on and can only be held together by Sovereign power. What if we developed systems based on love, trust, joy and kindness, aiming for the peace and wellbeing of all (including the environment?) – what might such a health system be like? It will take a social movement for us to get this shift, and as I wrote in my previous blog: You might call this a re-humanisation of our systems based on love, trust and the hope of a positive peace for all. But this social movement is not aiming for some kind of hippy experience in which we are all sat round camp fires, singing kum-ba-yah! This social movement is looking to cause our communities to flourish with a sense of health and wellbeing, to have a health and social care movement that is safe, sustainable, socially just and truly excellent, serving the needs of the wider community to grow stronger with individuals learning, growing and developing in their capacity to live well.

Kenotic power is vulnerable but it is not about being a door mat. It is like a beautiful martial art, in which we can say “I won’t fight you and you can’t knock me down, unless I let you” In other words, we lay down our rights and power freely, they are not taken from us by force. So, even when energetic attacks are launched against us, this kind of power allows us to move out of the way, allow the attack to pass through and then to come along side the person and help them see another point of view. Switching to this kind of power is far more creative, less combative and far more fruitful in creating a way ahead full of possibilities without the need for making enemies in the process. We must challenge the deep structural belief that our political and economic systems must be built on and can only be held together by Sovereign power. What if we developed systems based on love, trust, joy and kindness, aiming for the peace and wellbeing of all (including the environment?) – what might such a health system be like? It will take a social movement for us to get this shift, and as I wrote in my previous blog: You might call this a re-humanisation of our systems based on love, trust and the hope of a positive peace for all. But this social movement is not aiming for some kind of hippy experience in which we are all sat round camp fires, singing kum-ba-yah! This social movement is looking to cause our communities to flourish with a sense of health and wellbeing, to have a health and social care movement that is safe, sustainable, socially just and truly excellent, serving the needs of the wider community to grow stronger with individuals learning, growing and developing in their capacity to live well.

I agree wholeheartedly that the most important role of leaders is to cede their power, so that all can truly flourish, where there is a far greater sense of cooperative and collaborative agency within our (health) systems. But if we do not examine the nature of this power, we will only perpetuate our problems.

Martin Luther-King said these famous words – they are seriously worthy of our reflection:

Martin Luther-King said these famous words – they are seriously worthy of our reflection:

“Power without love is reckless and abusive and love without power is sentimental and anaemic. Power at its best is love implementing justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.”