This week I had the privilege of listening to Prof Warren Larkin, advisor to the Department of Health on Adverse Childhood Experiences. This is something I’ve written about on this blog before and Warren has made me more determined than ever to keep talking about this profoundly important issue. This blog draws on his wisdom and learning.

I believe that Adverse Childhood Experiences are our most important Public Health issue. So I want to be really clear about what they are, how and why they affect us so deeply, where we can find help if we’ve been affected by them and how together we can change the future, by preventing them.

What Are Adverse Childhood Experiences?

• Physical abuse

• Sexual Abuse

• Emotional Abuse

• Living with someone who abused drugs

• Living with someone who abused alcohol

• Exposure to domestic violence

• Living with someone who was incarcerated

• Living with someone with serious mental illness

• Parental loss through divorce, death or abandonment

How Common Are They?

The answer is – far too common. There have been some really wide ranging studies across the UK and USA into the numbers of us who have experienced ACEs, and it’s not just in our “most deprived communities” but in predominantly white, middle class areas where we see the stark statistics. Depending on the study you read, between 50 and 65% have experienced at least one ACE. And shockingly 1 in 10 of us have experienced more than 4.

How and Why Do They Effect Us?

Firstly, they affect us by quantity. The more ACEs we experience, the worse our physical, mental and social health and wellbeing is. If you have experienced one ACE, you have an 86% chance of being subject to several. If you experience more than 4, your health and wellbeing is significantly affected. If you experience more than 6 then you have a 46 times higher chance of becoming an IV drug abuser, a 35 times higher chance of committing suicide and an overall 20 year decrease in life expectancy.

Secondly, the toxic stress levels significantly change the way in which our brains grow and function. This has a profound impact on our day to day functioning. ACEs are a massive cause of absenteeism from work, high cost to the health and social care system and highly predictive of time behind bars. That is why so many of us have complex relationships with things like food. Losing weight, for example, is not as straight forward as eating less, exercising more or ending up with a gastric band. Did you know that suicide rates are massively increased after bariatric surgery? By removing the ability to eat, the very thing that takes away or comforts the pain, we expose the underlying issue, but provide no healing into that void.

Thirdly, our bodies literally keep the score of the negative experiences. So, we become more likely to develop chronic pain, inflammatory conditions, heart disease, cancer and mental health issues.

Fourthly, the toxic stress actually alters the way our DNA works and therefore changes the genetic information that we pass onto future generations. As an example, domestic violence in pregnancy is predictive of child developmental issues and offspring of the survivors of the holocaust or genocide are far more likely to develop chronic anxiety. This highlights just how important our family history really is.

Fifthly, there are proven things we can do a) to help our brains learn how to cope in the midst of really difficult circumstances (resilience) and b) therapeutic interventions that can genuinely heal us.

Where Can We Find Help?

Here’s the thing – this is where the rubber hits the road.

Many of us, who have experienced difficult things in childhood/adolescence never talk about them. Sometimes that’s because we can’t remember the experiences – they happen to us before our memories fully form. But perhaps more frequently we bury them because we don’t want to talk about the deeply painful memories, we don’t know how to or we’re worried about what might happen to us, or the people who caused us the pain if we do. And how do you start a conversation like that anyway? What? Are you going to just blurt it out to someone? And what on earth will you do if you just start crying in the middle of a restaurant when you talk to your girlfriend/boyfriend about what happened to you? And what about all those complicated associated feelings of shame, guilt, fear, thoughts of rejection? So…..we keep the lid on….even though it’s to our own detriment because we don’t know how to bring it into the open.

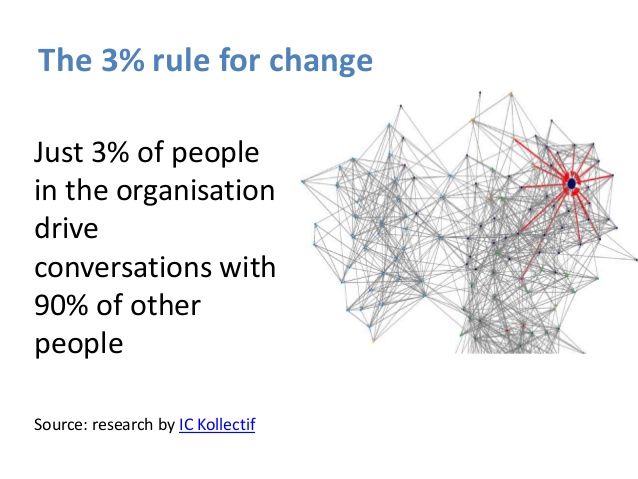

And here in lies the starting place. It’s vital that we learn this in the world of health and social care, but actually we all need to hear this incredible truth. Various studies have shown that it takes 9-16 years for people to be able to talk about trauma/abuse they experienced, but most never do. Fraser and Read found that in their patients struggling with mental health issues, only 8% of them volunteered that they had experienced ACEs. However, when they were actually asked about this, 82% then talked about ACEs they had experienced. So? So, we find it almost impossible to talk about, but when someone asks us about what we have lived through, it takes the lid off the box, peels the sticky plaster off the deep wound and allows us to begin talking about our pain. And here’s something really remarkable……Felitti and Andra found in a study of 140000 people that simply by routinely asking all patients about ACEs, they saw a 35% decrease in visits to the GP and an 11% reduction in use of the Emergency Department!

What does that mean? It means that giving someone the chance to talk about their journey, what they have been through, breaking the cycle of shame, fear and rejection is, in and of itself, deeply healing! Knowing that you’re not a freak, knowing that it wasn’t your fault, knowing that it doesn’t mean that you yourself will become an abuser/alcoholic/poor parent and many more realisations can make a significant difference to a person’s wellbeing. Maybe it doesn’t have to wait for a GP’s surgery or a counsellor’s chair. Maybe, just maybe if we all care enough to ask each other deeper and more caring questions we can help to heal each other. I know this is true of my own journey and that of many of my friends.

But let’s not be naive. For some of us, the experiences we have had are so horrific that we are stuck in a moment and we can’t get out of it. And this is where good therapy really comes in. I wonder if we invested more in therapy and less in drugs to numb our pain, how much more healed we might be – perhaps more expensive in the short term, but overall the cost is far less, both for the individual and society as a whole. There is help available and it can take many forms. EMDR, Trauma Focussed-CBT, Bereavement Counselling and even things like working through a forgiveness process. Unfortunately, many of the waiting lists are very long, and private options are way too expensive for most people to afford.

So, Can We Change The Future?

You know that I believe together we can! But it’s not going to be easy, especially not in the context of our floundering social services, restrictive school curriculums, reduction in numbers of health visitors and school nurses, eye watering cuts to public health budgets and significantly stretched CAMHS and Adult Mental Health Teams. And I think we have to very real and honest about that, because if this is such a massive issue in our society (and the data and evidence is astounding) then we need, as Warren Larkin so eloquently argues, genuine commitment from leaders and organisations to shift towards a culture of learning and collaboration to bring about change.

Here are some things we need to do together:

1) Own up to what a massive issue this is.

2) We need to learn how to ask our friends better questions and care enough to listen to each other’s experiences and journeys because it is really hard to know how to start talking about ACEs, but is more possible when someone bothers to ask!

3) We need to recognise that by bottling things up, we do further harm to ourselves. Perhaps some of our complex addictive patterns of behaviour, our mental health issues, our physical pain and symptoms might well be linked to the ACEs we have experienced. So maybe we don’t need a life on painkillers, cigarettes or with a complex addictive behaviour patterns. Maybe we can find a way to deeper healing.

4) In health and social care, we need to adopt REACh (routine enquiry about adversity in childhood) – we need to change the way we take histories from patients and ask better questions. Remember that even by asking, it doesn’t open up scary and messy consultations that we don’t have time for, actually it opens up a therapeutic space which can massively alter how a person goes on to use the health service in the future.

5) We need to ensure schools are more vigilant to thinking that ‘naughty’ or ‘difficult’ children are actually highly likely to be in a state of hyper vigilance due to stressful things they are experiencing at home. Expecting them to ‘focus, behave and get on with it’, is not only unrealistic, it’s actually unkind. Simply recognising that kids might be having a really hard time, giving them space to talk about it with someone skilled, teaching them some resilience and finding a way to work with their parents/carers via the school nurse/social worker could make a lifetime of difference. It is far more important that our kids leave school knowing they are loved, with a real sense of self-esteem and belonging than with good SATS scores or GCSEs. The academic stuff can come later if necessary and we need to get far better at accepting this.

6) Parenting classes should not just be for the well-motivated or struggling. They should be for all of us – a routine part of antenatal care and alongside our children’s education and include help in dealing with previous ACEs, so they are not repeated for the next generation. Prevention is possible. And that means we need to learn to be a whole lot less judgemental and a great deal more open, honest, vulnerable and restorative with each other. One of my best memories of growing up, was going to a “foster home” for families that my mum used to work with and seeing parents being given the chance to learn how to love their kids, rather than have them taken off them. I know sometimes there is no choice, but helping people learn how to be family and to love and cherish their children is a really beautiful thing. When there has been generational abuse, it is is also of the upmost importance. I’m not saying that a child should never be removed, but we can hardly say that our care system is a rip-roaring success story.

7) We need to find a way of working with men and women in our prisons that enables them to find a way to healing and restoration, not retribution for what are often extremely complex stories.

8) We must learn from best practice around the world. For example, did you know that the vast majority of paediphiles begin offending at the age of 14?! Most of them do not go on to become prolific offenders, but the damage caused to the child they abuse is obviously significant. There is some amazing work now going on in Pennsylvania which has shown that you can actually prevent young men from becoming offenders in the first place. Simply by doing some better sex education, explaining to boys about testosterone, the urges they are having and who it is appropriate to perform sexual acts with; alongside creating a really safe space where they can come and talk about feelings they are having (a bit like AA – with no ridicule or judgement) – data shows that you can decrease the incidence of child sexual abuse. We have to learn from this kind of approach and find a better way of talking about difficult issues. Prevention IS possible!

9) We need to find a way to fund more psychological therapies and become much less reliant on drugs to numb the pain with the associated colossal bill paid to Big Pharma.

This is an area I am really passionate about. I am committing to keep this conversation alive, to ensure that we make a shift in our organisations towards a REACh approach, to find a deeper and more effective partnership with colleagues in education, social services and the police and to create space for more training and awareness for all our staff teams. I know how painful this conversation is, but I also know how utterly damaging it will be if we don’t change the future and prevent this from being a perpetual story through the generations. It is time for the hearts of the elders to turn to the children. Together we can reimagine the future. Together we can.

Here is a really helpful film:

Are we taking seriously the Public Health England, World Health Organisation and World Health Innovation Summit advice seriously to write health into ALL policies? If so, will the expansion of Heathrow improve or worsen health outcomes, given that air pollution is the second biggest attributal cause to early death in England? How much consideration is given to health outcomes currently when it comes to transport, energy or business policies?

Are we taking seriously the Public Health England, World Health Organisation and World Health Innovation Summit advice seriously to write health into ALL policies? If so, will the expansion of Heathrow improve or worsen health outcomes, given that air pollution is the second biggest attributal cause to early death in England? How much consideration is given to health outcomes currently when it comes to transport, energy or business policies?