If you haven’t yet had the chance to read the Kings Fund’s vision for population health (and it’s the kind of thing that interests you) then I would heartily recommend that you do so. (https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/vision-population-health). It is a real ‘Tour de Force’ and deserves some significant consideration. I like it because it doesn’t hold back from bringing some hard-hitting challenge, but also creates hope of what is possible.

Last week, whilst I was in Hull, I unpacked some of my (many) thoughts about population health, drawing on the wisdom of this report, the significant challenges we face and the opportunity we have to reimagine the future, together with our communities. I was hoping to offer it as a podcast, but it didn’t record well! This is quite a long read, but I hope encapsulates the key issues and gives us plenty to wrestle with and discuss, reflecting on the great piece of work from the Kingsfund.

When it comes to population health, we have to remember, especially when we look at a global stage, that the UK has had some of the best public health in the world. We have so much to be  grateful for and have had some incredible breakthroughs in our health and wellbeing over the last 200 years. Consider how our life expectancy has increased, initially through the great improvements in clean water, sanitation and immunisations and then the emergence of the NHS, with free healthcare for all, no matter of ability to pay, and subsequent lifesaving interventions in the areas like hypertension and diabetes – we’ve come a long way, though there is still plenty of work to do!

grateful for and have had some incredible breakthroughs in our health and wellbeing over the last 200 years. Consider how our life expectancy has increased, initially through the great improvements in clean water, sanitation and immunisations and then the emergence of the NHS, with free healthcare for all, no matter of ability to pay, and subsequent lifesaving interventions in the areas like hypertension and diabetes – we’ve come a long way, though there is still plenty of work to do!

However, there is a lesson in humility that we need to take from the All Blacks (consistently the greatest sports team in the world). After successive world cups, which they should have won, they had to take a good, long and hard look at themselves and face up to this uncomfortable truth – they were losing! (and I imagine after the mighty victory of the Irish against them recently, they may be having the same conversation again). We have to face up to the fact that right now, in terms of population health, especially around health inequalities, we are losing and we’re losing BIG. 1 in 200 of us is currently homeless. Childhood poverty is increasing year on year and many of our children go hungry on a daily basis. According to the Food Foundation, our poorest 5th of households would have to spend 43% of their entire income to eat the government’s recommended ‘healthy diet’. Much of our housing stock is unfit to live in. Our healthy life expectancy gap between the rich and the poor is nearly 20 years, with a shocking difference between the North and the South. We have a mental health crisis in our young people, with suicide the leading cause of death by some mile in Males under 45. And to top it all, we have a severe shortage of staff in the NHS and our public services which make it actually impossible to continue the level of service required by the heavy target-driven culture of Whitehall.

However, there is a lesson in humility that we need to take from the All Blacks (consistently the greatest sports team in the world). After successive world cups, which they should have won, they had to take a good, long and hard look at themselves and face up to this uncomfortable truth – they were losing! (and I imagine after the mighty victory of the Irish against them recently, they may be having the same conversation again). We have to face up to the fact that right now, in terms of population health, especially around health inequalities, we are losing and we’re losing BIG. 1 in 200 of us is currently homeless. Childhood poverty is increasing year on year and many of our children go hungry on a daily basis. According to the Food Foundation, our poorest 5th of households would have to spend 43% of their entire income to eat the government’s recommended ‘healthy diet’. Much of our housing stock is unfit to live in. Our healthy life expectancy gap between the rich and the poor is nearly 20 years, with a shocking difference between the North and the South. We have a mental health crisis in our young people, with suicide the leading cause of death by some mile in Males under 45. And to top it all, we have a severe shortage of staff in the NHS and our public services which make it actually impossible to continue the level of service required by the heavy target-driven culture of Whitehall.

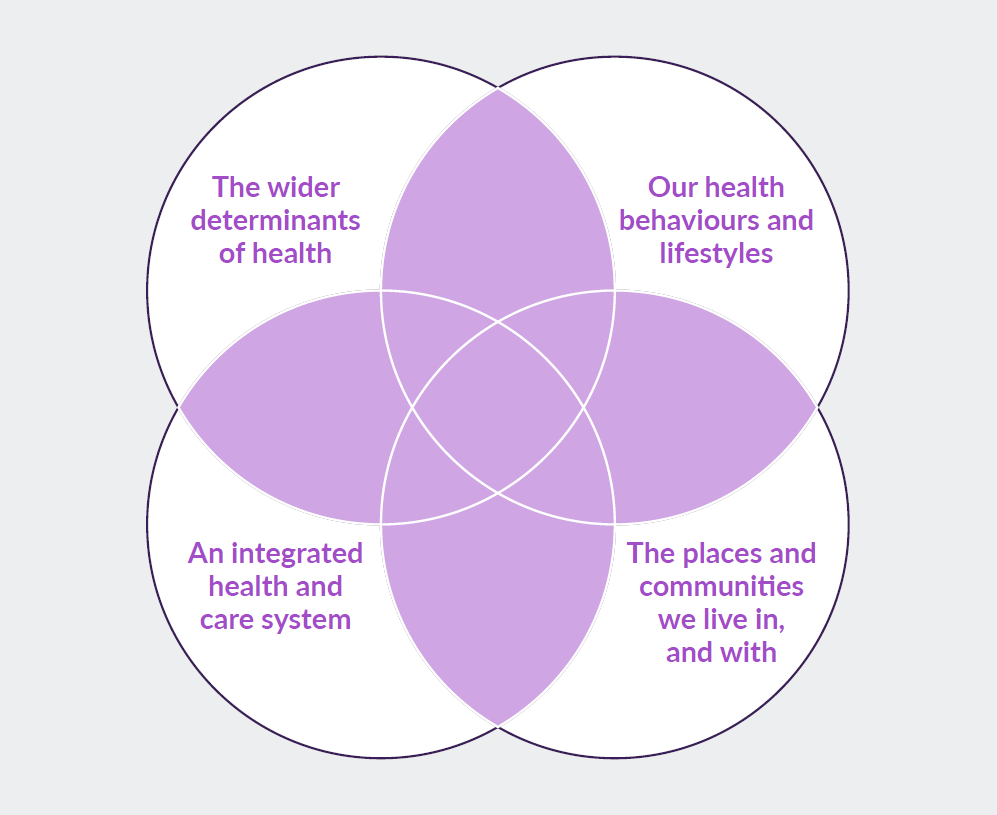

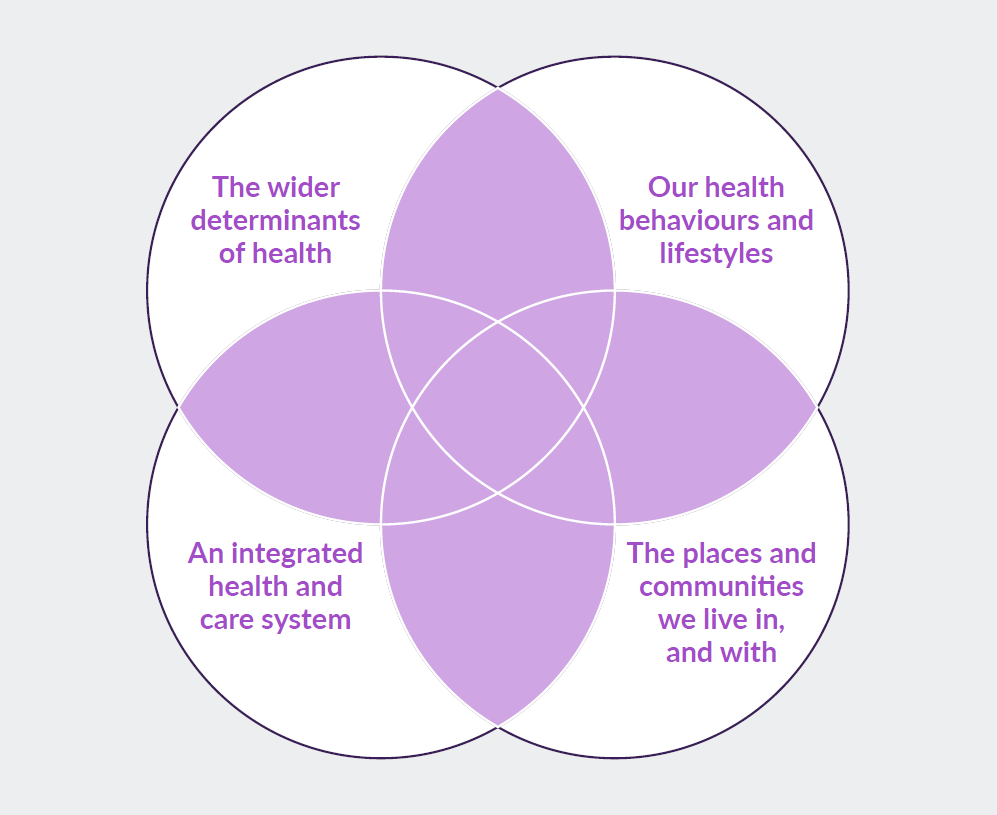

To continue trying to deliver the same services in the same way, when these issues are so starkly in front of us, is beyond insanity. We simply cannot continue to continue with business as usual and think that we will achieve anything different or new. This is why I like the 4 interlocking pillars the Kingsfund recommend when thinking about population health and I will unpack some thoughts about each one.

thoughts about each one.

The Wider Determinants of Health

Before I start on this section, it is really important for me to state that despite what others have at times accused me of, I am not actually a member of any political party and so when I write things which challenge current government policy or praxis I am not trying to score political points. In fact, I believe it is one of the key purposes of (health) leadership to call out when decision making processes are harming the health and wellbeing of the population (whether intentionally or not). Indeed, the same would apply, whoever was in (seeming) power.

When it comes to tackling the issues of population health, dealing with health inequalities and ensuring that the health and wellbeing of all people and the planet is taken into account in every government policy, the current administration is found sorely wanting. No matter what is peddled out about the “successes” of Universal Credit (which I do actually believe was introduced with some good intentions), it is failing and will continue to fail as necessary safeguards are not being put in place. Since the introduction of UC, we have seen a staggering rise in the use of food banks. Families, especially children are going hungry and the financially poorest in our society are not having their basic nutritional needs met. Since 2010, we have seen childhood poverty rise and the health inequalities gap widen. Much of this is owing to the burden of austerity being carried primarily by our poorest communities. In this same time period, we have seen the loss of overall goals for population health and no clear directives or measures to encourage change. In fact, many of the more project and target driven approaches to population health are often the very things that cause a worsening of health inequalities, like child obesity initiatives, because they do not focus on the wider determinants of health like poverty, housing and planning.

On one level, we should applaud Matt Hancock, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care for encouraging the NHS to get into the game of prevention. However, a mirror then needs holding back up to the government to examine what this really means. It is clear that the current ‘rise’ in funding for the NHS, won’t even enable business to continue as usual (and one might argue that’s a good thing, because we need to change business as usual – except for the fact that there is no letting up on the drivers and targets from the Department of Health that continue to maintain the current modus operandi). The £3.4 billion per year increase won’t even touch the hole in our acute hospital trusts, let alone account for the whopping >49% of total cuts from local government (more than £18 billion in total, with more to follow), who are absolutely instrumental in tackling the wider determinants of health and wellbeing. Public Health, which has always been so vital to the work of prevention has been decimated within local governments, who are struggling to keep their statuary services up and running. So, no, it’s not actually that straightforward for the NHS just to now take on the responsibility of prevention, as the social determinants and wider economic issues, including funding aspects, are an absolutely vital component of getting population health right and asking the NHS to do so, simply piles more pressure on an already stretched and burned out workforce. An ending of austerity and an appropriate level of funding is vital if we are to achieve population health, uncomfortable truth for the government, though this may be.

On one level, we should applaud Matt Hancock, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care for encouraging the NHS to get into the game of prevention. However, a mirror then needs holding back up to the government to examine what this really means. It is clear that the current ‘rise’ in funding for the NHS, won’t even enable business to continue as usual (and one might argue that’s a good thing, because we need to change business as usual – except for the fact that there is no letting up on the drivers and targets from the Department of Health that continue to maintain the current modus operandi). The £3.4 billion per year increase won’t even touch the hole in our acute hospital trusts, let alone account for the whopping >49% of total cuts from local government (more than £18 billion in total, with more to follow), who are absolutely instrumental in tackling the wider determinants of health and wellbeing. Public Health, which has always been so vital to the work of prevention has been decimated within local governments, who are struggling to keep their statuary services up and running. So, no, it’s not actually that straightforward for the NHS just to now take on the responsibility of prevention, as the social determinants and wider economic issues, including funding aspects, are an absolutely vital component of getting population health right and asking the NHS to do so, simply piles more pressure on an already stretched and burned out workforce. An ending of austerity and an appropriate level of funding is vital if we are to achieve population health, uncomfortable truth for the government, though this may be.

Our Choices, Behaviours and Lifestyles

There is a worrying rhetoric finding voice that ‘people should just make better choices and take more responsibility for themselves’, but this is simply far less possible for so many of our communities than others, as a direct result of policy decisions and economic models over which they have no power or control.

One one level, no one would argue that each of us has at least some level of responsibility to make positive lifestyle choices, make good decisions about what we put into our bodies and how much exercise we do or don’t take. But we must remember that this is so much easier for vast swathes of our population than others.

There is plenty of evidence though that helps the NHS think about where to focus when it comes to population health management – where we can make the most difference. These areas include: smoking, alcohol, high sugar intake, high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation, high cholesterol (currently hotly debated!), healthy weight and positive mental health. Remember though, Sandro Galea’s work on ubiquitous factors! It is possible to focus in on projects like these and make health inequalities worse! These things cannot be done in isolation, but must be part of a wider vision. The temptation will be for governments to focus on these narrow interventions and claim great statistical significance whilst still not dealing the root issues.

It is in this that again, we need to see the government come up trumps. Targeted and smart taxation can have a massive impact on the choices we make – we know this through the massive breakthrough we’ve seen in smoking in recent years. The same now needs to be applied to the highly influential, powerful and dangerous sugar industry. A best next step, according to Professor Susan Jebb, from Oxford University, would be to put a substantial tax on biscuits and cakes. Like it or not, along with our carb obsession, these are our biggest downfall and if the government are actually serious about tackling our ‘obesity epidemic’ then they need to break any cosy ties with this industry and stop the nonsense about being too much of a nanny state. Public opinion, which apparently hates the nanny state, thinks the smoking intervention was fantastic and the benefit is clear. The role of government is to see what damages our health and work with us to help modify that behaviour.

An Integrated Health and Care System

There are plenty of places around the country where we can now begin to see the potential and power of working together differently. In the UK, Wigan, with great leadership from the likes of Kate Ardern, tells a powerful story of how incredible things can happen when population health is owned by everyone and a social movement is born. Manchester, with its devolved budget, political  stability and holistically embedded view of population health championed by the Mayor of the City, Andy Burnham is a fine example of how working together differently can really offer some exciting possibilities. He recently said this:

stability and holistically embedded view of population health championed by the Mayor of the City, Andy Burnham is a fine example of how working together differently can really offer some exciting possibilities. He recently said this:

“As Secretary of State for Health, you can have a vision for health services. As Mayor of Greater Manchester, you can have a vision for people’s health. There is a world of difference between the two!”

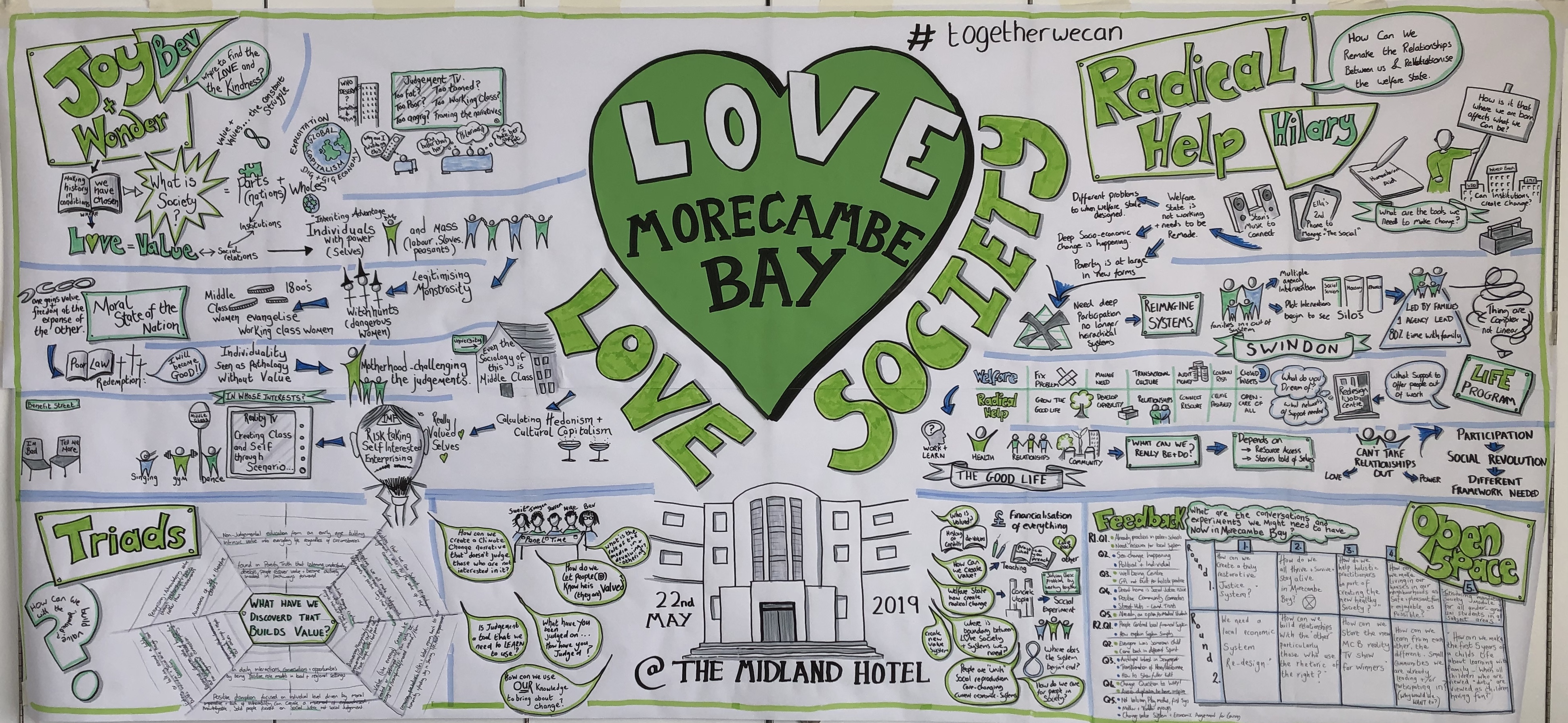

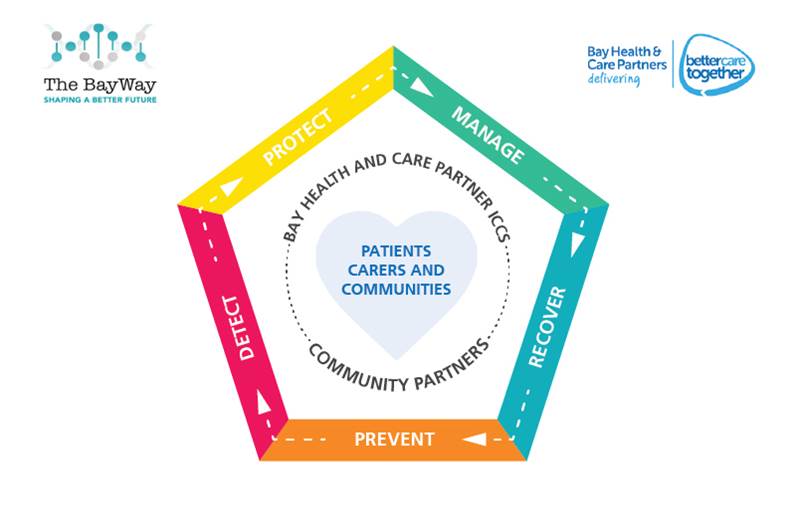

In Morecambe Bay, as an integrated care partnership within the wider Lancashire and South Cumbria ICS, we have already found some huge benefits in working more closely together. It gives us an opportunity to find solutions to the wicked issues we face through collaboration and combined wisdom, rather than through competition and suspicion.

The integration is important at the macro level (where decision making and budgeting occurs), as well as in the micro level in our neighbourhoods. Our Integrated Care Communities in Morecambe Bay are without doubt one the instrumental building blocks we have to reimagining how we can deliver care more effectively for our communities. In each of our 9 areas around the Bay we have teams involving GPs, the hospital trust, social workers, allied health professionals (physios, OTs), police, fire service, community nursing, community and voluntary teams, faith organisations, and councillors working together for the good of our local neighbourhoods.

The Places and Communities we Live in and With

Place is hugely important and so is community. Isolation literally kills us. We have certainly found in Morecambe Bay, that choosing to work differently WITH our communities, rather than doing things to them is fundamental in being holistic when it comes to Population Health and Wellbeing. It has meant learning to take our lanyards from around our necks, getting out of our board rooms (where traditionally we take decisions on behalf of people) and embracing humility as we learn to listen to and partner with our communities. One book I have found really helpful, personally has been ‘The Nazareth Manifesto’ by Samuel Wells. He is considered by some to be the ‘greatest living theologian’, and I consider it to be of vital importance for us to think and engage with these issues of heath and wellbeing as widely as possible, including theology, philosophy, sociology and economics, to help challenge and inform the necessary mindset shifts which are needed. Wells writes that for him, the entire Christian story is encapsulated in these 4 words: “God is with us”. Whatever, you happen to believe about God, there is certainly a majority view that if there is a God, he tends to be quite aloof, distant, hierarchical, dominating, controlling and power-crazy, if not seriously vengeful at times – and interestingly, we often refer to some leader-types as having a ‘God complex’! But if God is not like that, but is primarily about being WITH people, not over them, working WITH them rather than doing things to them, that has huge implications on much of western thought and how we set up leadership and governmental institutions!

Place is hugely important and so is community. Isolation literally kills us. We have certainly found in Morecambe Bay, that choosing to work differently WITH our communities, rather than doing things to them is fundamental in being holistic when it comes to Population Health and Wellbeing. It has meant learning to take our lanyards from around our necks, getting out of our board rooms (where traditionally we take decisions on behalf of people) and embracing humility as we learn to listen to and partner with our communities. One book I have found really helpful, personally has been ‘The Nazareth Manifesto’ by Samuel Wells. He is considered by some to be the ‘greatest living theologian’, and I consider it to be of vital importance for us to think and engage with these issues of heath and wellbeing as widely as possible, including theology, philosophy, sociology and economics, to help challenge and inform the necessary mindset shifts which are needed. Wells writes that for him, the entire Christian story is encapsulated in these 4 words: “God is with us”. Whatever, you happen to believe about God, there is certainly a majority view that if there is a God, he tends to be quite aloof, distant, hierarchical, dominating, controlling and power-crazy, if not seriously vengeful at times – and interestingly, we often refer to some leader-types as having a ‘God complex’! But if God is not like that, but is primarily about being WITH people, not over them, working WITH them rather than doing things to them, that has huge implications on much of western thought and how we set up leadership and governmental institutions!

Hilary Cottam’s book, Radical Help and Jeremy Heiman’s and Henry Timms’ insights in New Power are both vital reading in really engaging with this whole concept. We need to radically embrace the fundamental truth of relationship as an agent for good and change in our society. Our public services have become devoid of real and genuine relationships with our communities.

Over the last 3 years as we have had many conversations around Morecambe Bay, being honest about the financial predicament we find ourselves in (needing to save £120m over the next 5 years, 1/5th of our total budget, whilst still meeting all our targets!) and listening to each other as we try and work out how we can be more healthy and well together, so many beautiful and amazing things have started. These include: mental health cafes, community choirs, the Morecambe Bay poverty truth commission, walking groups, the daily mile in our local schools, new ways of working between the police, council and local communities, the voluntary sector working differently together, dementia befriending, mental health courses in our schools, a new focus on adverse childhood experiences and many many more.

So Where from Here?

I believe we find ourselves in an intersectional moment in which we can unlock a very different kind of future than the one we appear to be currently heading for. It is time for deeper listening and a reimagining of how we really might live in a way together that cedes health and wellbeing of humanity and the planet through everything we do. This means we can honour previous ways of doing things, recognising where some of them have been detrimental and contradictory to true population health, letting go of our insanity in the process and find a new, more healthy way forward. It is vital that we consider these four interactive pillars of population health and embed them into every facet of our life together in society. This means ownership and resulting policy change by the government with funding that actually works for the kind of integrated, living and flexible systems we need to co-create. We need communities to find new ways of being well together, take responsibility for our own lifestyles and behaviours, with compassion and kindness for whom this is less than easy.

From my perspective this would mean a reimagining of politics – a rediscovery of how we live well together – away from binary competition and white male privilege and towards collaborative  inclusivity and equality, based on love, kindness and compassion aka “kenarchy” in which we renegotiate our relationship with power. It would mean a reimagining of economics – a recalibration away from transaction and a ‘use and abuse biopower’ towards a ‘doughnut economics’ in which we learn to live in the sweet spot of environmental sustainability and human justice and mercy.

inclusivity and equality, based on love, kindness and compassion aka “kenarchy” in which we renegotiate our relationship with power. It would mean a reimagining of economics – a recalibration away from transaction and a ‘use and abuse biopower’ towards a ‘doughnut economics’ in which we learn to live in the sweet spot of environmental sustainability and human justice and mercy.

There are so many things that we have accepted and reports we have ignored. It is time for us to collectively say “enough now” to that which is dividing and killing us and hold together the reality of despair and hope in our communities, as we allow the reality to sink in that together WITH each other, we really can begin to find an altogether better future for us all and the planet. It won’t be easy and means there are many of our own personal ego structures, deep wounds and problematic behaviours that will need healing and changing along the way, but let’s open our eyes and allow new eye light to help us see the future which in our hearts we are longing for.