https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/nhs-10-year-plan

This is an excellent blog from Sir Chris Ham and Richard Murray at the Kingsfund and highlights some important issues that deserve real consideration and debate. Get a cup of tea, reflect on it and then join the discussion. Here are my reflections on it.

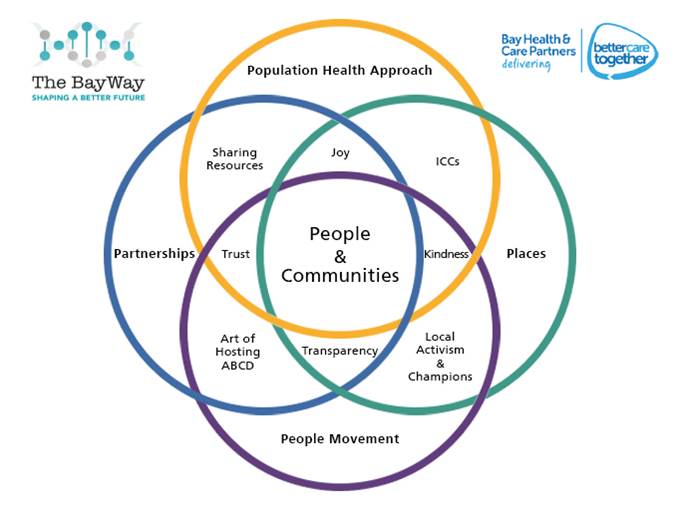

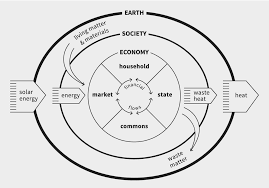

Improving population health and closing the health inequlaity gap are the two most important things for the NHS to focus on, if we are to have a heath and care service that works for everyone and is sustainable long into the future. It is not an easy nettle to grasp and is full of complexity, which is highlighted in this paper, but fundamentally, if we do not see a cultural shift, and ownership of these issues across the public sector, with population (and environmental) health written into every policy combined with a collaborative social movement for change, we will still be talking about this in another 15 years.

The reorganisations of the last few decades have been exhausting at so many levels and have not achieved what we have needed them to. It is indeed vital that we learn from these lessons and commit to at least a 10 year focus on improving population health, tackling health inequalities and integrating services, ensuring that we embed a culture of joy, kindness and excellence as we do so. We have reached a pivotal moment and we must break through our silos and see things tip towards a new commitment to improve the population’s health, together.

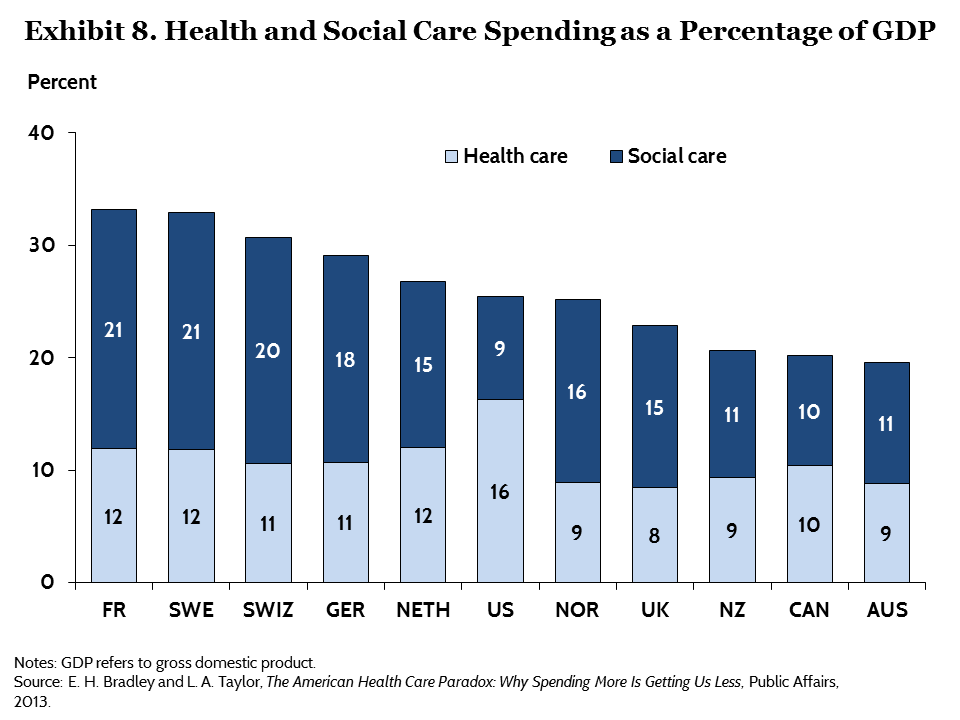

The funding question will not go away and it is really important that we are honest and open about what is actually going to be possible within the new funding agreement for the NHS and what will not be, especially if there is not a substantial investment into Social Care. Much of what we mean by prevention in Population Health relies heavily on other public sector partners, like Public Health, Education and the Police and the reality of their funding decline will make the transformation we need to see, especially in young people’s mental health very difficult, especially as the new deal for the NHS is not what it needs to be. For many Integrated Care Systems, the savings still required are so colossal that doing the simulataneous transformational work of population health and tackling the widening health inequality gap is a very hard task. It is a huge ask of finance directors to meet the constant demands of the regulators whilst also trying to be brave and shift resource towards more long term gains that do not meet the short termism of yearly budget requirements. The increase in demand due to more frailty and complex health issues, eye watering cuts to local government budgets (with profound knock-on effects to social care and public health), a target driven environment and low staff morale is making this all very difficult. It is not impossible but it is going to need realism and pragmatism about what can be achieved, by when. The choices being made about the funding of our public services are ideologically driven, and we need to ensure that feedback about the reality of austerity leads to necessary changes, so that we can have truly evidenced based policies.

Here in Morecambe Bay, we have recently launched the ‘Poverty Truth Commission’, one of several around the country. Many leaders from across our region sat with tears streaming down our faces as we heard story after story about the reality of poverty and destitution for people in our area. We heard from one young man, Daniel about how the closing of the youth centre on his estate and his local high school (both the only places where he knew he belonged and was safe), left him and many of his friends vulnerable to gangs. Moved, again and again through private rented housing, in order to provide for his siblings, he ended up selling drugs and guns, simply to put food on the table, ending up street homeless, with serious addiction problems himself. Many of us wondered how often we think about the short and long term consequences of the cuts being made and what kind of risk assessment is done in these situations. In her very powerful book, ‘Radical Help’, Hilary Cottam writes of need to put relationship back into the heart of our public service care provision, as we grapple with the joint issues of funding constraints and human need.

The points raised about improving productivity are important. Where we can be more efficient, we must continue to be so. Let’s pause to recognise, though, just how much has been achieved already. Culturally, we must learn to celebrate the positives and recognise the great work already being done in this area, which will inspire more of the same. The sharing of best practice and creating environments where we can learn from one another is absolutely key. This will most effectively happen through collaboration not competition. So, yes – integration must be a priority, but it comes with a health warning – if we don’t get culture right from the start, everything else will ultimately fail.

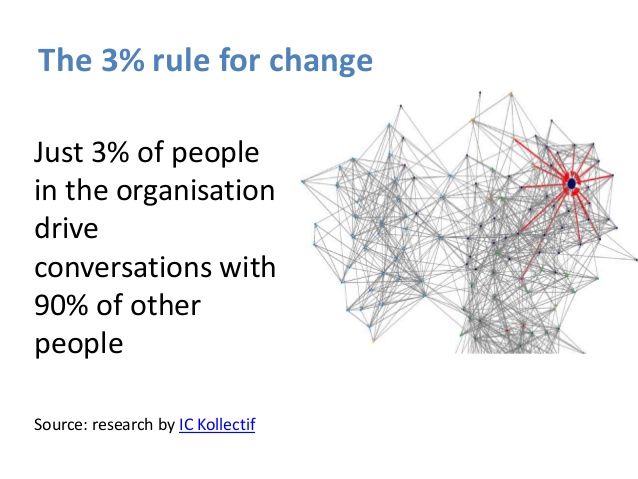

A Population Health approach is the only game in town. Wigan have achieved some really wonderful things, but there are some important things to understand about the context of Wigan that have made it more possible there. Firstly, there is clear political unity. The idea of population health is owned across all spheres and levels of government, and “safe seats” have led to a political continuity that has made long term planning far more successful. The ongoing politicisation of health and social care in other contexts makes this kind of transformation much more difficult. Secondly, there is a real humility in style of leadership that has been willing to a) openly share the complex issues and choices being faced, with the people of Wigan and b) deeply listen to the communities and therefore find a way through the problems together with a profound sense of joint ownership. It is this two-edged sword of necessary culture change and brave leadership with a social movement that makes it possible to cut into new ground together. We must be brave in talking to people in our local communities about the choices ahead of us and understand the importance of agreeing together who is going to take responsibility for the various pieces of th jigsaw which need to occur.

We know that 40% of our health depends on the every day choices we make as individuals, for example around what we eat or how much exercise we take. However, it is not as lovely and simple as this. There is far less choice available for our most deprived communities. Supermarkets do not stack the same amount of healthy food in their shops in our more deprived areas. Children have little choice over the adverse experiences they go through, how much sugar is in their breakfast cereal nor what is pushed at them through targeted advertising. The number of junk food outlets is far higher in areas of greater deprivation (see Greg Fell’s excellent analysis of Sheffield). So, when we talk about choice, especially in the context of poverty and education, we need to take a reality check and not simply point the finger of responsibility. This is where a people’s charter can be really powerful. Those in leadership play their part in taking care of the needs of the population and bringing in appropriate governance and a fair distribution of resource, whilst citizens commit to playing their part in staying healthy and well, and learning about conditions which they live with, so they can play an active role in being as well as possible, dependent on their circumstance.

Given the lessons from Wigan, or from global cities, like Manchester, and Amsterdam and what they are beginning to achieve around population health, there is a powerful argument, not only for combined health and social care budgets, but also for increased devolution of budgets. If we see what has been achieved in the Black Forest of Germany, with a very holistic transformation of services, including the connecting of communities through far improved transport links, we begin to reimagine what might be possible at a larger scale. Devolved budgets though must be a fair deal and not an opportunity for central government to make further cuts and then leave the blame in the locality. Devolution, if it is to work well, must come with new and fair legislation around taxation and proportionate allocation of resources.

All of this is only possible with the right workforce. I completely agree that we need both short-term and long-term strategies. I am not yet confident that enough work is being done at a predictive analytical level to really work out what kind of workforce we will require, if we shift to a fully integrated, population health model. This is the kind of workforce we must then build and it will by its very nature, be much more community and relationally focussed. This will allow us to build culture from the ground up and create the kind of working environments that are healthy and well, enjoyable to work in and therefore with a high retention level of staff. Perhaps our short term solutions need to be less reactionary and more proactive in building towards the future we need. Perhaps there are also more short term international opportunities and partnerships to be built whilst we plan for our reimagined future.

In making all of this happen, I think we need a little caution in too much over-comparrison with the American insurance-based systems. The ICS development we see there is based on a very different model and can look very appealing, because it overlooks too readily the 50million Americans who cannot afford a decent level of care. Yes, there are some impressive things to learn and some very data savvy things we can apply into our systems, but the fundamental differences between our ideologies and practices must cause us to pause and think about what is transferable and what we can do diffferently to ensure that everything we do works to close the health inequality gap, rather than widen it. This is where our greatest test will be. It is too easy when creating new agreements with the public to work with those who are already highly motivated to change. In so doing, we might actually make things worse, rather than better in terms of inequality. It is going to take determined effort and brave focus to ensure this doesn’t happen.

In short (!) I am very grateful for this paper and the issues it highlights. It deserves real contemplative reflection and a commitment by all to embrace this future together. We cannot achieve population health and the tackling of health inequalities alone, but together, we can.