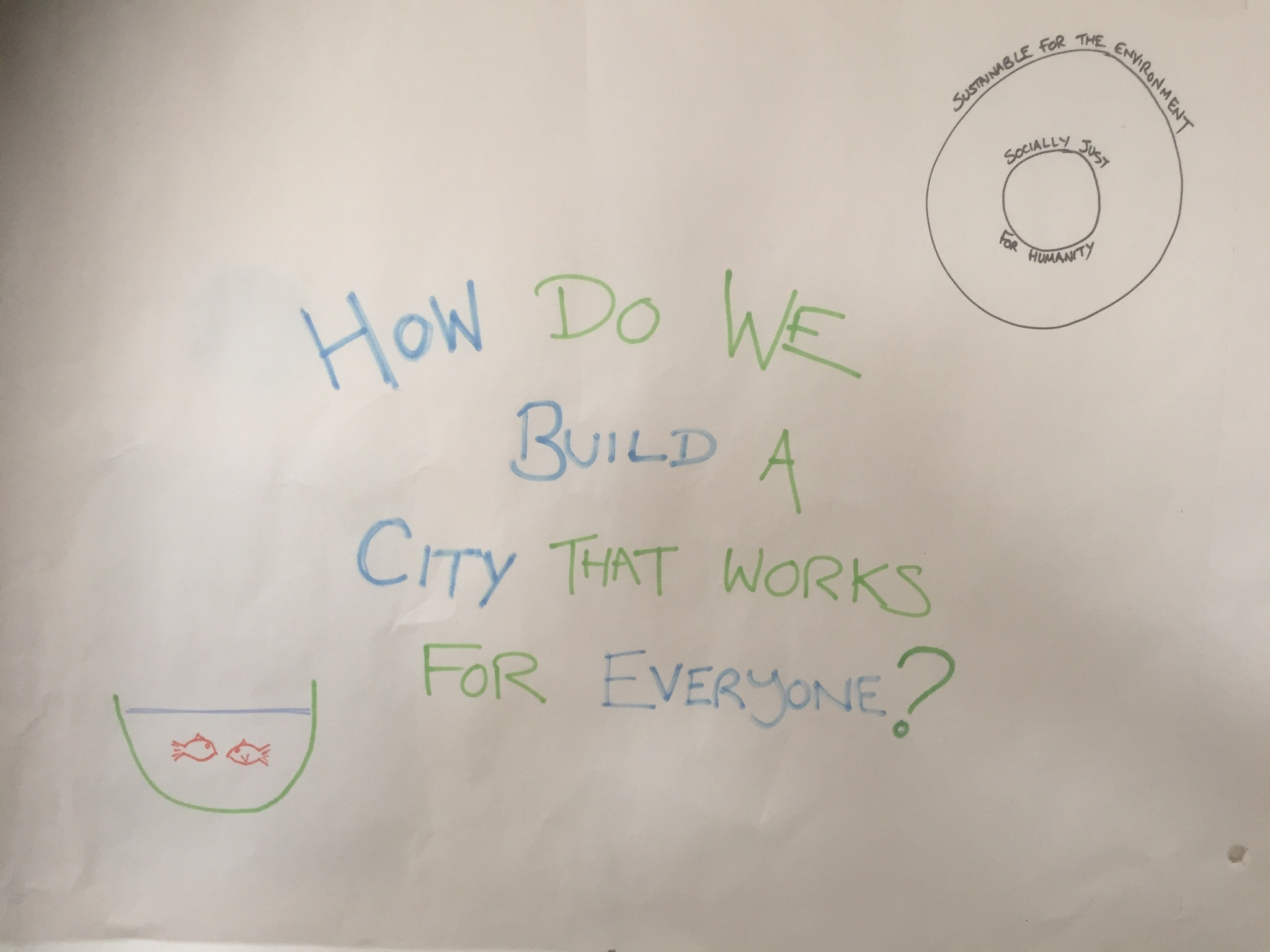

I recently hosted a couple of conversations for people in the city of Lancaster, UK, in which we explored this question together: “How Do We Build a City that Works for Everyone?” We framed the conversation (which we had using a ‘World Café’)from two current and important concepts. Firstly, the great work of Kate Raworth in ‘Doughnut Economics’ – how do we create a city that is socially just for the people who live here and that is environmentally sustainable for the future? In other words, how do we ensure we have an economy that is distributive and regenerative by design? Secondly, we drew on the important work of Sandro Galea (Professor of Epidemiology at Boston State) and his concept of the Goldfish bowl as a way of thinking about ‘Population Health’ or Epidemiology (see my last blog). Politics IS health, according to Galea.

I recently hosted a couple of conversations for people in the city of Lancaster, UK, in which we explored this question together: “How Do We Build a City that Works for Everyone?” We framed the conversation (which we had using a ‘World Café’)from two current and important concepts. Firstly, the great work of Kate Raworth in ‘Doughnut Economics’ – how do we create a city that is socially just for the people who live here and that is environmentally sustainable for the future? In other words, how do we ensure we have an economy that is distributive and regenerative by design? Secondly, we drew on the important work of Sandro Galea (Professor of Epidemiology at Boston State) and his concept of the Goldfish bowl as a way of thinking about ‘Population Health’ or Epidemiology (see my last blog). Politics IS health, according to Galea.

One of my favourite quotes is from Einstein, when he said that “If I had 60 minutes to save the world, I would spend 55 minutes trying to find the right question and then I could solve the problem in 5 minutes.” It turns out that the question we used itself is problematic at a few levels! Here are some of the questions we found ourselves wrestling with: Do we need to build the city, when it is already here?! What do we really mean by ‘the city’ – is it people and communities or more than that? What do we mean by ‘works for’? That felt to some like we were settling for something that was just enough, maybe scraping by, rather than thriving! And who do we mean by everyone?! This didn’t stop us having a a great discussion, but highlights how powerful the perspectives and biases we bring into the room can be!

Despite not having a perfect question, (and hopefully, by the time we host 3 much bigger conversations across the city during 2019, we may have honed something more helpful!), some key themes emerged, through our generative conversation.

- Relationships are vital! We want to live in a city which really does “work” for everyone. So, we want to give value to the currently unheard voices and we want to value diversity and inclusivity. Taking time to get to know neighbours and colleagues grows a richness of community. We want to live in a city that values love and kindness in how we treat ourselves and other people.

- We need to build on the amazing assets and skills that we already have in the city. If we made space and time to discover and share these skills with each other more, we would develop a richer life experience within our communities. This is an expression of ‘gift economy’ and ‘reciprocity’, which Charles Eisenstein writes powerfully about in his book ‘Sacred Economics’). It builds on voluntary power, and may require a reimagining of how we work and what we value in how we invest our time, energy and resources. We also have so many incredible physical assets in this area, which we don’t tap into enough or perhaps make fully accessible for all who live in the city.

- People want to be part of the change, not have change happen to them! This requires much better engagement and democratic discussion about how budgets are spent, for example or how land is developed. Somehow, there needs to be a better safeguarding against ‘invested interests’ and ‘dodgy deals’ with far more transparency about how decisions are made. Such a process, it is believed, would enable far better personal and corporate responsibility when it comes to caring for the fabric of the city and the people who live here, similar to what has been developed in Wigan. There was a recognition that when we talk about personal choice and responsibility that this is much more possible for some people and communities than others. However, it was felt that increasing self-esteem and a sense of belonging would enable more personal responsibility and choice.

- Housing really matters. The physical environment is actually causing fragmentation and silos. There were many more questions than answers here – but that’s ok – this is an iterative process, and we don’t have to solve everything in one go. So…how do we create really good social housing? How could we redesign the spaces of the city to encourage togetherness and community? How do protect green spaces in the process and take care of the city’s drainage (strong memories of the recent floods)? How could we ensure that everyone has a home to live in, and what might that mean for both the homeless and also for single people?

- We want an education system that really values the unique beauty of each child, treats each one with compassion, mindful of what traumas they may be experiencing and values creativity and activity in education just as much as academic outcomes. We care about who our children become, not just about what exams they pass. So we recognise that we have a measurement problem but we’re not quite sure yet what to do about it!

- We need to invest in our children and young people by providing physical spaces in which our young people can feel safe and not bored! Many have been affected by the closure of children’s and youth centres. If we are to really invest in our children and young people, there was a sense that we also need to provide parenting classes across the board to pregnant couples and through ‘family centres’ and schools across the district.

- We want to create a greater sense of value for our older citizens. There were many people present who felt they have things to offer, but don’t have an obvious outlet. Involving those retired from paid work more in the life of the city would break isolation and feed the gift economy.

- Business needs to thrive in a way that really values entrepreneurial gift and allows it to flourish, whilst holding it true to the ideas and principles of the doughnut and the goldfish! How could the business community serve the needs of the city and how can the city enable business to really thrive, creating jobs, whilst caring for the environment and the needs of the people who live here? Kate Raworth’s work could really help us!

- Transport systems need to be redesigned to encourage more cycling and walking or the use of green public transport alternatives. Transport routes also need to join up our communities more effectively to improve opportunities for those who live in areas that are currently more financially deprived.

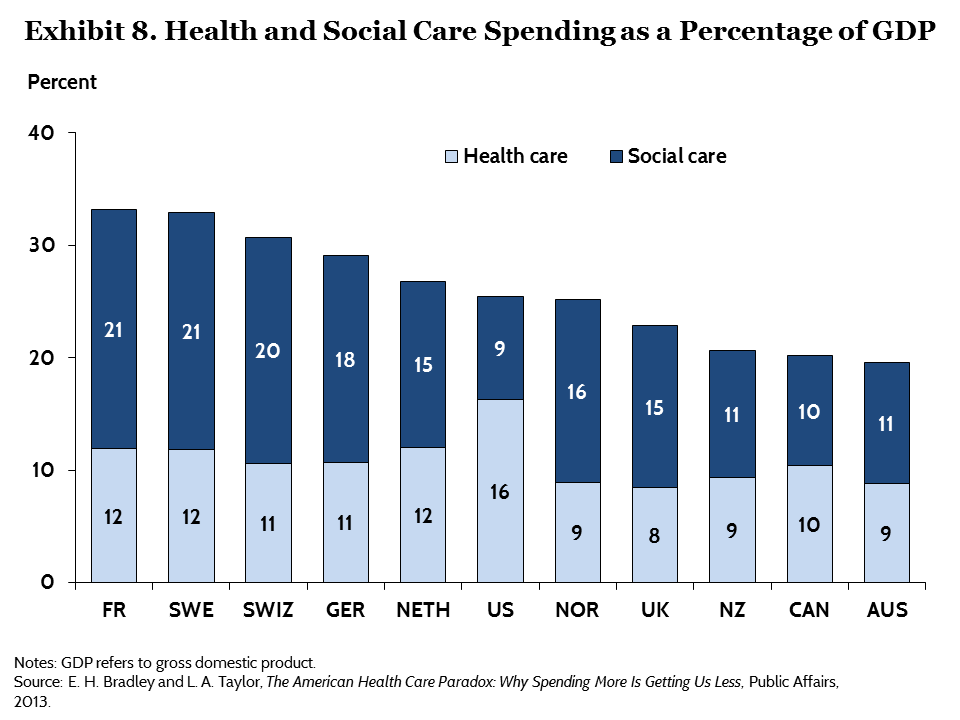

- If we are to really improve health and wellbeing and care for the environment, then we need to see this written into EVERY policy decision. If politics IS health, as per Sandro Galea, then we need to take this seriously and stop making policies which do not care for these things.

- We want to be part of city that does welfare well! We think there are many possible new ways of doing things more effectively, as described in Hilary Cottam’s book, ‘Radical Help – Reimagining the Welfare State’. One of the things felt to be important is increasing skills in money management (85% of people living in social housing in this district are in debt to the city council -though this is certainly not only due to poor money management , but an unjust system that isn’t working for the majority). Morecambe Bay Credit Union offers an alternative economy as a way of using micro finance in our local geography.

- We need better ways to communicate and connect people together. There is smart, digital technology that could help us here….perhaps a Lancaster portal, that connects us together more effectively and helps facilitate the sharing of our assets and gifts.

Wowsers! Not bad for 2 conversations of 90 minutes each! Just imagine what a phenomenal city Lancaster might become over the next 10-20 years, if we set out on a journey together to build this kind of city! What is stopping us, I wonder?! #enoughnow #togetherwecan