One of the best things I have been involved in over the last few years, is the Poverty Truth Commission and it has helped me to learn just how utterly complex and wicked poverty is as an issue. I’m currently reading an absolutely brilliant book by the theologian Samuel Wells, called ‘The Nazareth Manifesto’. In it, he makes the most accurate diagnosis of poverty that I have ever seen and it rings true of my work in clinical practice, my years of helping out in homeless projects in Manchester, my time spent in Sub-Saharan Africa, the poverty truth commission and my involvement in projects around food poverty.

Wells recognises the biggest issues in our society right now are caused by our massive obsession with mortality and our drive to overcome our human limitations. Using poverty as an example, he goes on to demonstrate that none of our current under-girding political or economic philosophies will get us even close to addressing the real issue. Our real issue is that we are isolated and dislocated and our breakdown in relationship leads to the deep sickness that we have in society right now. I don’t think I have ever seen this United Kingdom so utterly divided and truthfully, none of our current available options will bring us the unity we need to heal, forgive and find an altogether kinder and more sustainable future, together. It is our division which leads to the stark contrasts in life expectancy of people who live just six miles apart in Morecambe Bay. It is our dislocation that leads to such different life stories in Chelsea from the people who so tragically lost their lives in Grenfell. It is the disconnection between the City of London and Tower Hamlets that allows such gulf between the rich and poor.

When we look at the NHS 10 year plan, (apart from the fact that there isn’t the workforce around to deliver it and our local government budgets have been so utterly decimated that the gaping hole in public health and social care will ensure the plan fails), it is based on a defunct philosophy of needing to overcome our limitations. The NHS cannot save us from our current sickness of separation and isolation and nor can we expect it to.

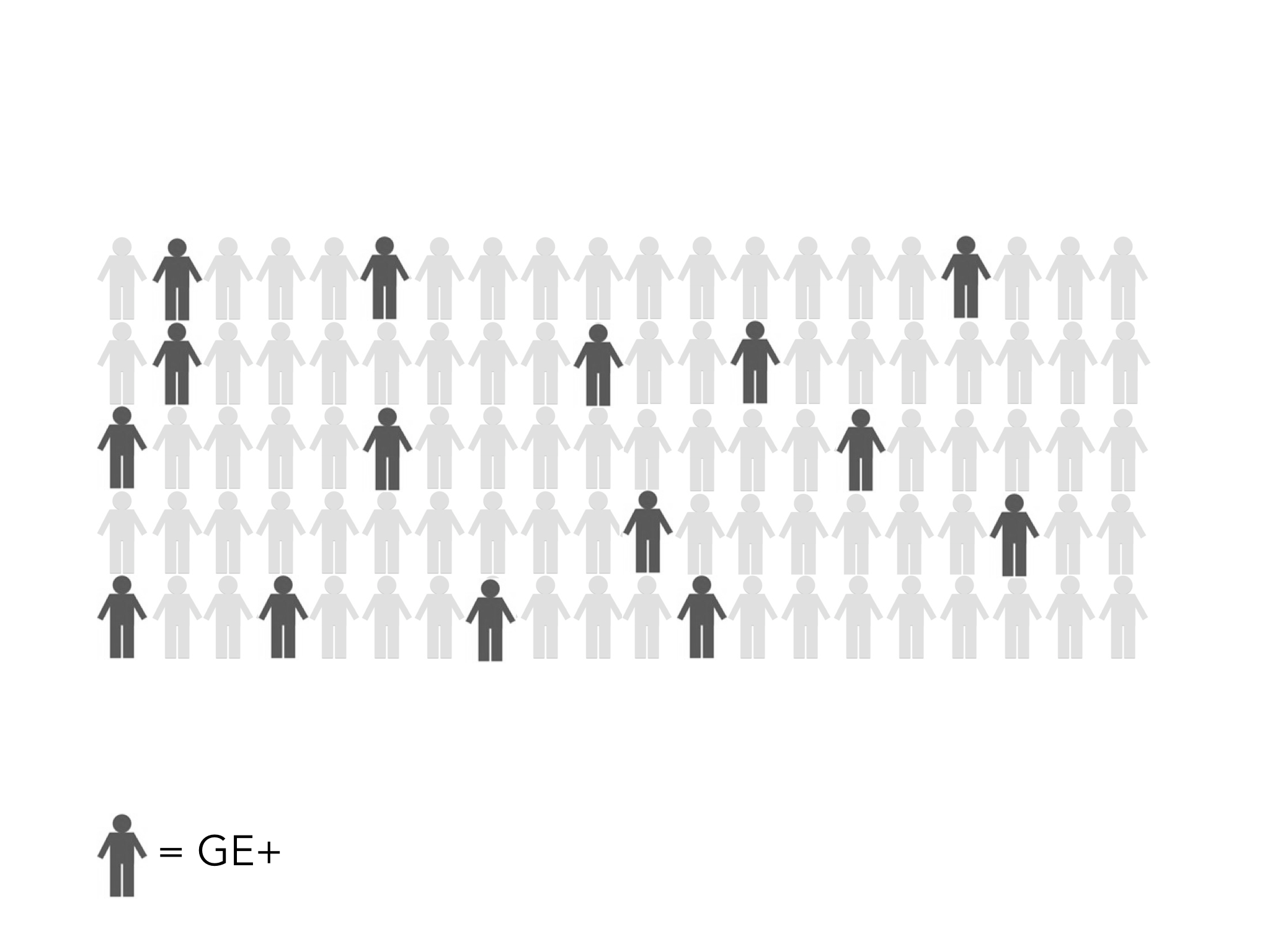

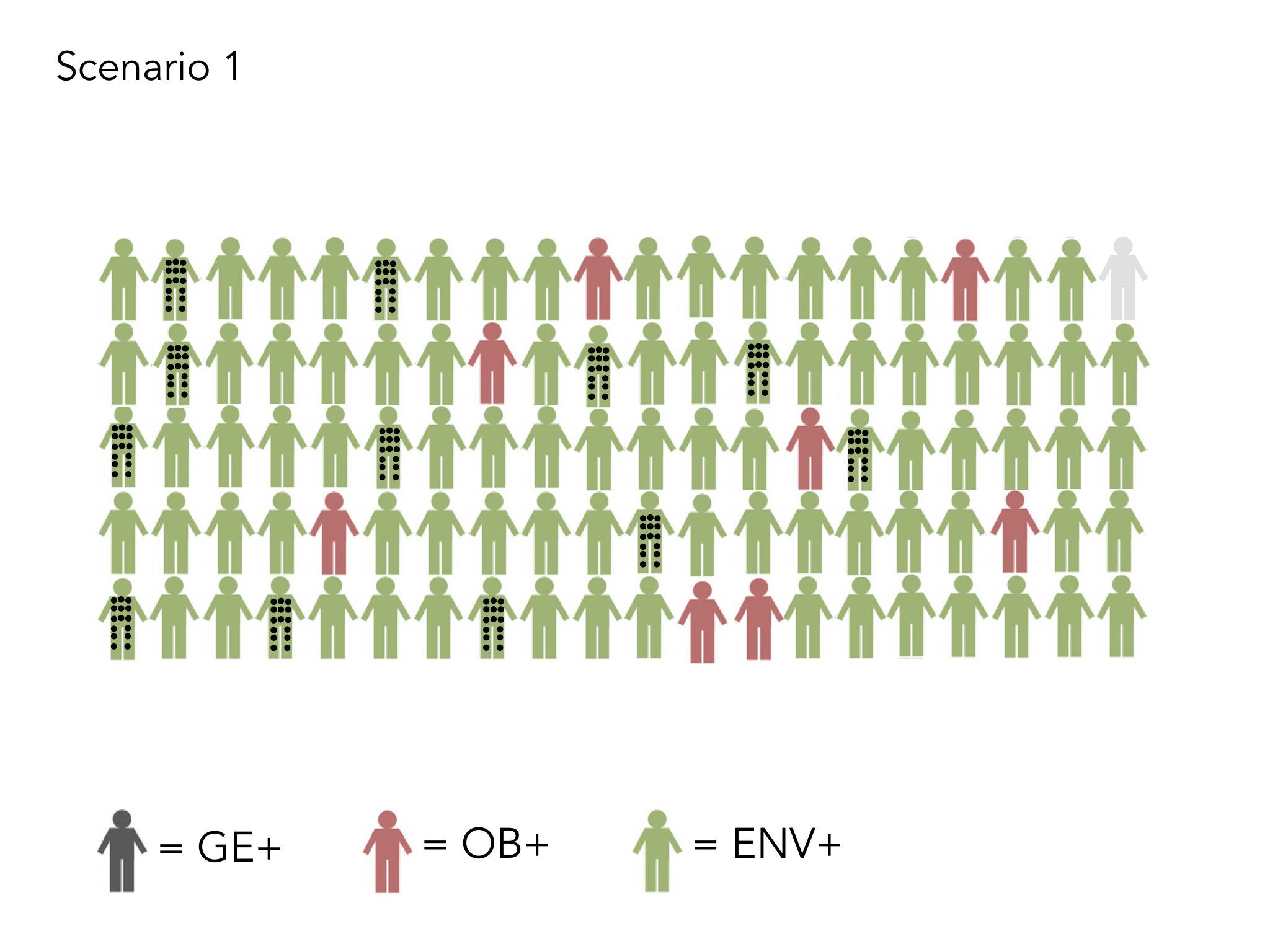

Taking the example of poverty, Wells examines our current motifs for explaining this very complex issue and what it shows us about society. Poverty is currently explained through either Deficit or Dislocation. The ‘deficit metaphor’ can be illustrated in three ways:

- The desert narrative explains that people are poor because the do not have enough (of whatever) and so this can be ‘fixed’ by transferring resources. However, he shows this is deeply flawed as a parable because it dehumanises those who live in poverty, creating an ‘us and them’ mentality in which the rich/powerful try and fix the issue via ‘quasi-colonial’ approaches or use things like food aid to effectively control local populations in abusive ways.

- The defeat narrative focuses more on winners and losers and takes quite an unhealthy emphasis on the role of ‘personal responsiblity’ without really considering the other very complex factors like public policy and housing prices….

- The dragnet narrative is what the Millenium Development Goals are actually based on (see ‘The End of Poverty’ by Jeffrey Sachs) and considers poverty to be a dragnet/trap which makes it impossible for the poorest to even get onto the bottom rung of the ladder so people can climb out. It focuses on redistribution of wealth via 0.7% of GDP but is very paternalistic and is about doing to or working for, rather than a collaborative ‘together with’ approach.

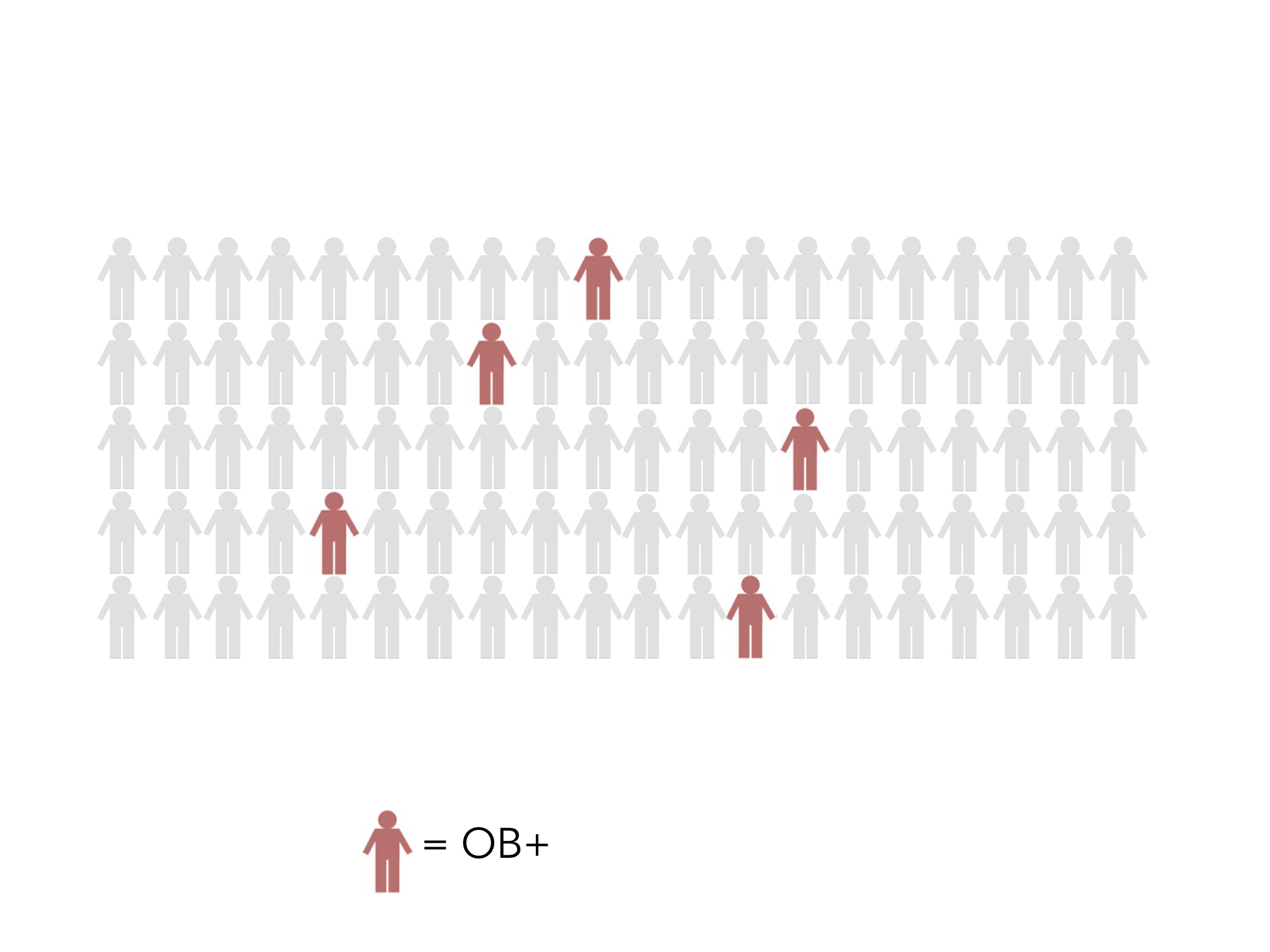

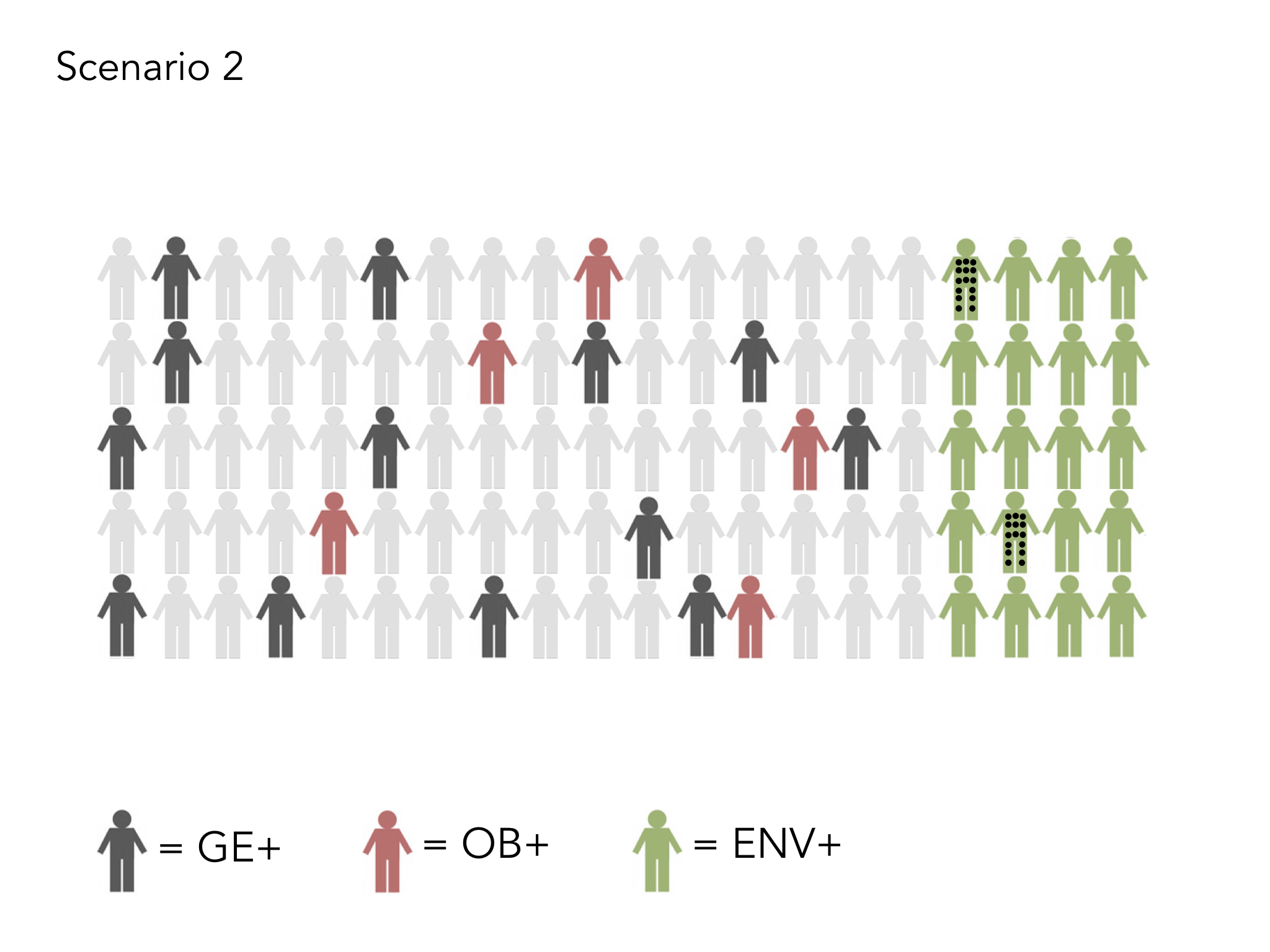

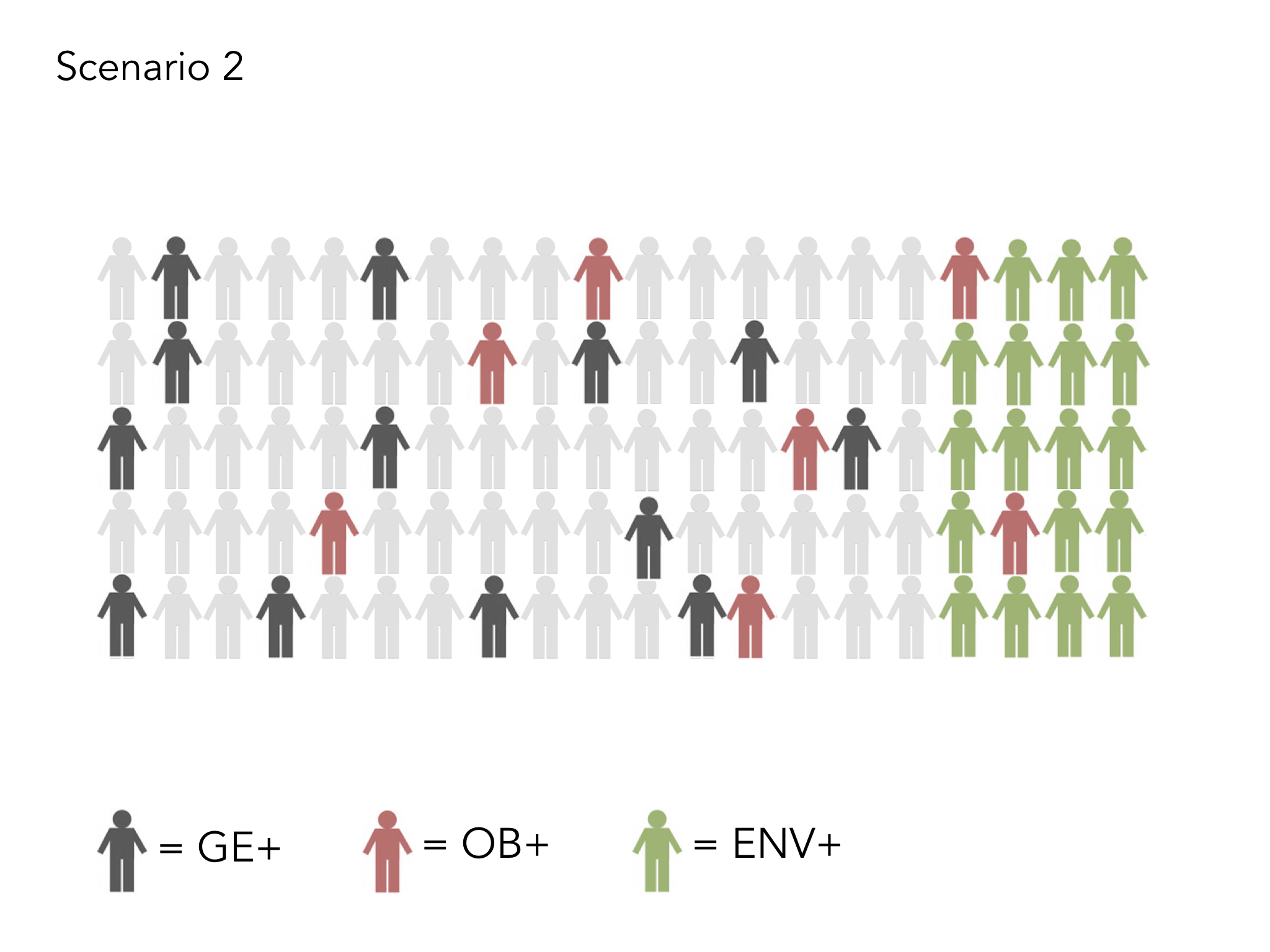

The ‘dislocation metaphor’ likewise can be understood in triplicate:

1. The dungeon narrative explains poverty not as scarcity but as sin. It is either due to the sin of people who unjustly lock up the poor through their own greed and unfair policies. Or it is understood as the sin of people through making bad choices and therefore ending up trapped in their own prison. However, it still relies on external factors to fix it and so generally remains highly paternalistic.

2. The disease narrative explains poverty as a sickness which lives in our relationships, communities and societies. It recognises that, just like disease, poverty is extremely complex and multifactoral and so does not focus on apportioning blame.

3. The desolation narrative focusses on symptoms>causes, for example how the reality of poverty has a far greater effect globally on women than men – leading to major injustice, oppression and abuse of women across the globe.

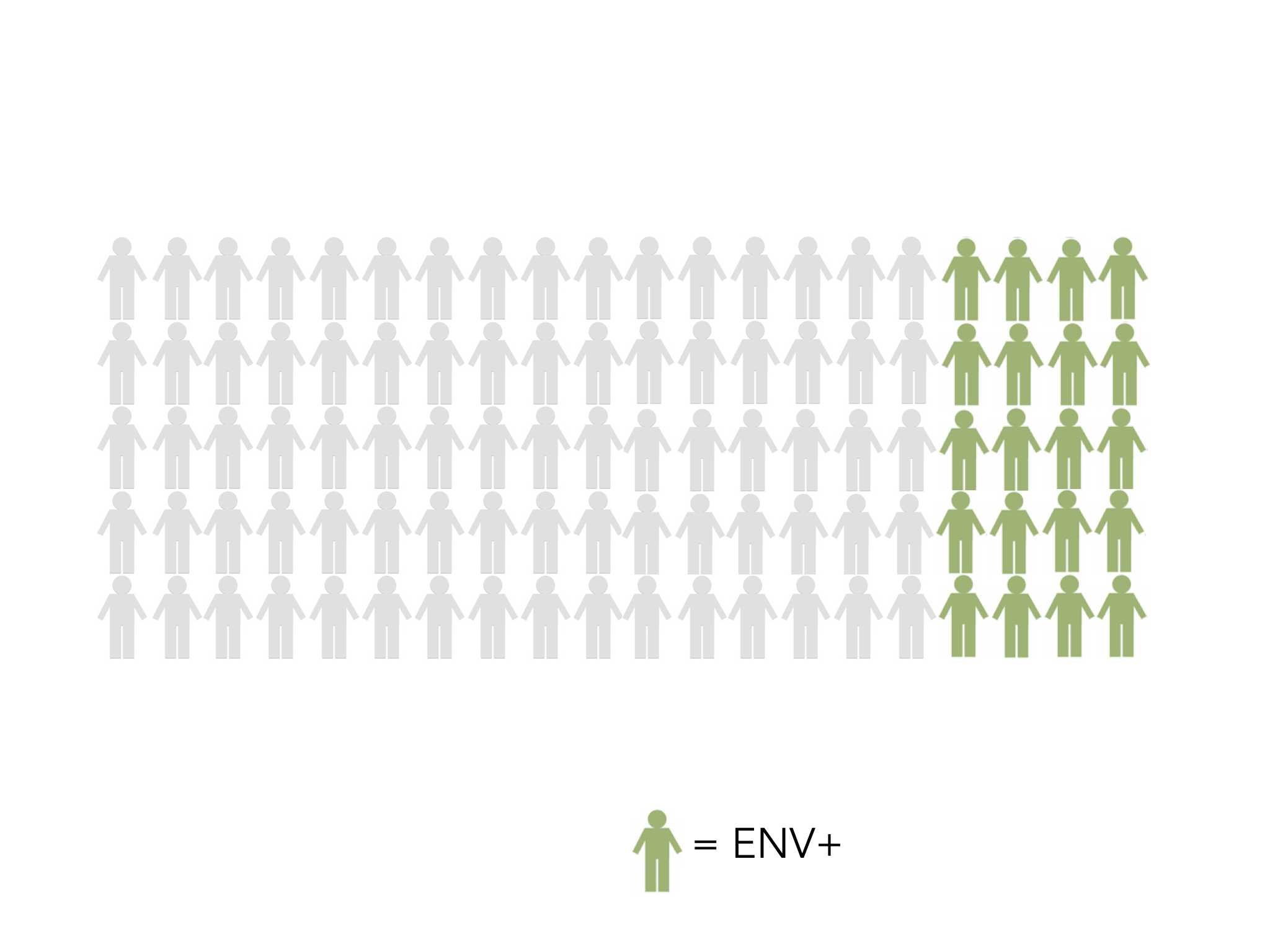

Wells argues that the reality of poverty, whether local or global is primarily due to isolation and our obsession with mortality and overcoming human limitation is actually making our isolation even worse and therefore making us more sick. And for Wells, poverty is not fundamentally about the absence of money or the lack of conventional forms of power (although this is a part of it), but it is far more about the impoverishment, the industrialisation, the manipulation, the breakdown or the perversion of relationship. It is our isolation from one another that leads to exasperation, impatience, the pointing of fingers, blame and the villifation of ‘the other’. Just look at the polarisation on twitter between the right and left and the appalling name calling and slinging of mud and you see exactly what I mean.

The reality is that neither of our increasingly polarised political options is going to heal us or help us find a future that will be good for humanity or the planet. Our political ideologies are so opposed between liberty (right wing) and equality (left wing) but neither is equipped to help us break through this curse of isolation and find a new way forward together. I believe that we have reached a critical point in which we need to find an altogether kinder, more compassionate and collaborative politics and economics that is based first of all on humble listening and genuine democratic conversation to help us find a way forward together, rather than this current division and hatred. I believe as we find each other and build relationships (something which social media can so easily rob us of), we come to appreciate our different perspectives, learn from each other and find that we actually care about each other. I know, for sure, that by learning to BE WITH rather than DO TO or even WORK FOR has really changed how I see others and how I believe we can build a fairer and kinder society for everyone. It demands humility and forgiveness, based on a self-giving, others-empowering love as we build positive peace and requires of us, personal change and the dealing with our own self-centredness as we discover the beauty of connectedness to all people and all things. Theology shapes a great deal more of our philosophy and life together than many of us would care to accept! Well’s thesis is that the character of God is first and foremost discovered in these four words: ‘God is with us’. So often we think of people having a ‘God-complex’ who are people who think they know everything and do things to people because they know how to fix things. It smacks of arrogance. What if God isn’t like that at all? What if the most important thing to God is being with people? What if ‘being with’ is where it’s at and ‘doing to’ and ‘working for’ is to miss the point of what it means for us to be human and whole?

I wonder if we are brave enough to let go of that which is actually killing us and the planet and begin to find an altogether different way forward, together. Isolated, we die. Together we live.