Morecambe Bay

Known for it’s fast moving tides, mud flats, quicksands, islands, rare birds, natural gas, submarine building and nuclear power; Morecambe Bay is a place whose motto is “where beauty surrounds and health abounds”. The first part is true – it is a place with some of the most spectacular views on offer in the entire UK and hidden treasures of wildlife and wonderful walks. A place where I live with my family and I now call home. But it has some of the worst health outcomes in the country, sitting bang in the middle of the North-West – the worst place for health per head of population for any of the regions in the UK. We are the worst for cancer rates, the worst for heart disease, the worst for respiratory problems and the worst for early deaths. And please avoid the rhetoric that would have you believe that it is because of low aspiration and poor choices made by the people here. The North-West is underfunded in terms of health training, according to Health Education England, to the tune of £19 million every year, when compared head to head for other regions. And given the fact that health outcomes are so poor here, it is fascinating that 94% of all health research monies are spent south of Cambridge.

Known for it’s fast moving tides, mud flats, quicksands, islands, rare birds, natural gas, submarine building and nuclear power; Morecambe Bay is a place whose motto is “where beauty surrounds and health abounds”. The first part is true – it is a place with some of the most spectacular views on offer in the entire UK and hidden treasures of wildlife and wonderful walks. A place where I live with my family and I now call home. But it has some of the worst health outcomes in the country, sitting bang in the middle of the North-West – the worst place for health per head of population for any of the regions in the UK. We are the worst for cancer rates, the worst for heart disease, the worst for respiratory problems and the worst for early deaths. And please avoid the rhetoric that would have you believe that it is because of low aspiration and poor choices made by the people here. The North-West is underfunded in terms of health training, according to Health Education England, to the tune of £19 million every year, when compared head to head for other regions. And given the fact that health outcomes are so poor here, it is fascinating that 94% of all health research monies are spent south of Cambridge.

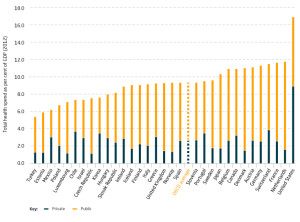

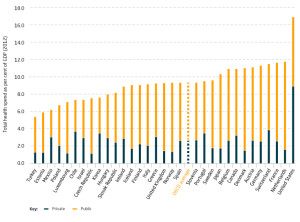

Looking at the health system here, it would be easy to be disheartened. The recent Kirkup enquiry into drastic failures at the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay Foundation Trust, to which the trust has responded with humility and learning, highlighted just how much change is needed here. We also face the vast complexities associated with local tariff modification. And as if the local challenges are not enough, we have the added recruitment crisis that is affecting the entire country (worse in rural areas), the undermining of our junior doctors and their pay, the berating of nursing colleagues from overseas who don’t get paid enough to remain here, severely low morale in the system as a whole, and a maltreatment of General Practice in the National Press at a time when the profession is on the ropes; then there is the huge debt of the hospital trusts – compounded by the PFI fiasco and the creeping privatisation of our services, which has led to the shambles that is out of hours care and staffing issues due to agency working. And  all that is on the background of a hugely underfunded healthservice, with only 8.5% of GDP spent on health compared to the 11% most other OECD countries spend. The truth is, we simply do not spend enough of our GDP on health care for it to be sustainable in its current form, and the government knows this.

all that is on the background of a hugely underfunded healthservice, with only 8.5% of GDP spent on health compared to the 11% most other OECD countries spend. The truth is, we simply do not spend enough of our GDP on health care for it to be sustainable in its current form, and the government knows this.

For the last three and a half years, I have been working here as a GP, having previously spent 14 years in Manchester. Three days a week, I work clinically in my practice, and the rest of my work time is given over to being part of the executive team for the Lancashire North CCG – I am the lead for Health and Wellbeing. Although the odds are stacked against us, something really wonderful is stirring here. I would go as far to say that believe it or not, Morecambe Bay is one of the most exciting places to be involved in health and social care anywhere in the UK. Let me tell you why I feel so hopeful (and why you should consider working here)!

Understanding the Purpose of Healthcare

A chap called, Phil Cass, who is an (unmet) hero of mine in the medical field, lives in the state of Ohio. He has been been doing some work with local communities to try and make healthcare affordable for everybody – a truly noble quest in a country where 50 million people cannot afford any. He took the conversation out to the community and they tried various questions, but found they weren’t really getting anywhere. He and team of people then realised that they needed to ask a better question. The question they needed to get to was “What is the PURPOSE of our healthcare system?” – Once the communities began engaging with this question, something remarkable happened – time and again, the same answer came through – the answer was this:- “to provide OPTIMAL healthcare to everybody.” The word optimal recognised that every person would achieve different “levels” of health depending on age, underlying health problems, genetics etc, but the vision of the community became that they wanted every individual and the community as a whole to live as well as they could. The community then realised that in order for this to be achievable, they had to fundamentally change their relationship with the healthcare system and this then made care much more affordable. Here in Morecambe Bay, we are taking a similar conversation to the 320000 citizens who live here.

A chap called, Phil Cass, who is an (unmet) hero of mine in the medical field, lives in the state of Ohio. He has been been doing some work with local communities to try and make healthcare affordable for everybody – a truly noble quest in a country where 50 million people cannot afford any. He took the conversation out to the community and they tried various questions, but found they weren’t really getting anywhere. He and team of people then realised that they needed to ask a better question. The question they needed to get to was “What is the PURPOSE of our healthcare system?” – Once the communities began engaging with this question, something remarkable happened – time and again, the same answer came through – the answer was this:- “to provide OPTIMAL healthcare to everybody.” The word optimal recognised that every person would achieve different “levels” of health depending on age, underlying health problems, genetics etc, but the vision of the community became that they wanted every individual and the community as a whole to live as well as they could. The community then realised that in order for this to be achievable, they had to fundamentally change their relationship with the healthcare system and this then made care much more affordable. Here in Morecambe Bay, we are taking a similar conversation to the 320000 citizens who live here.

Starting and Finishing with People

The NHS has become a horribly target driven culture and amidst the stress and strain, in which staff themselves often feel dehumanised, it is easy to forget what we are here for – human beings. Putting people (rather than patients) at the heart of how we think about health is a vital starting point.

So, we are learning to truly engage with and listen to the people here. With the help of an amazng team, I have been hosting conversations here in Carnforth, in the form of ‘World Cafe’ discussions (a fantastic way to ensure every voice is heard). Our hope is that from Millom to Morecambe, we will see conversations springing up as we talk about how Morecambe Bay can become the healthiest place in the UK. And by being healthy, we do not mean just physical health. We are talking about mental health, social health (there really is such a thing as society!) and systemic health (including issues like road safety – still the biggest cause of death for our children, the environment and pollution, the real effects of austerity on our communities, the power of advertising and the high cost of healthy food). And as we talk with our citizens, we are not coming in with ideas of how to fix things, as though we are some kind of experts. People are the experts in themselves the their communities, and we have some expertise in a variety of fields. So, we have a meeting of equals. We are waiting to see what rises within the communities themselves and looking to support initiatives where that is wanted. Communities are having some really exciting conversations and some people are standing up to become ‘health and well-being champions’ (the photo is taken from a recent event, supported by our Mayor in Carnforth, looking to do exactly that), who want to help steward the well-being of the community and the environment. It is incredible to see how many people want to get more involved with making this area more “healthy”. Volunteers are springing up with ideas like gorilla gardening, shopping for elderly neighbours, cooking meals for those coming out of hospital, setting up choirs, starting youth clubs, community transport services to help housebound people get to appointments, cleaning up our streets, creating safe parks and being hands on with support for those receiving palliative care. People are learning to ‘self-care’ and care for each other more effectively.

So, we are learning to truly engage with and listen to the people here. With the help of an amazng team, I have been hosting conversations here in Carnforth, in the form of ‘World Cafe’ discussions (a fantastic way to ensure every voice is heard). Our hope is that from Millom to Morecambe, we will see conversations springing up as we talk about how Morecambe Bay can become the healthiest place in the UK. And by being healthy, we do not mean just physical health. We are talking about mental health, social health (there really is such a thing as society!) and systemic health (including issues like road safety – still the biggest cause of death for our children, the environment and pollution, the real effects of austerity on our communities, the power of advertising and the high cost of healthy food). And as we talk with our citizens, we are not coming in with ideas of how to fix things, as though we are some kind of experts. People are the experts in themselves the their communities, and we have some expertise in a variety of fields. So, we have a meeting of equals. We are waiting to see what rises within the communities themselves and looking to support initiatives where that is wanted. Communities are having some really exciting conversations and some people are standing up to become ‘health and well-being champions’ (the photo is taken from a recent event, supported by our Mayor in Carnforth, looking to do exactly that), who want to help steward the well-being of the community and the environment. It is incredible to see how many people want to get more involved with making this area more “healthy”. Volunteers are springing up with ideas like gorilla gardening, shopping for elderly neighbours, cooking meals for those coming out of hospital, setting up choirs, starting youth clubs, community transport services to help housebound people get to appointments, cleaning up our streets, creating safe parks and being hands on with support for those receiving palliative care. People are learning to ‘self-care’ and care for each other more effectively.

Atul Gawande, another hero, has written powerfully in his book ‘Being Mortal’ (a manifesto for change in how the medical profession deals with the whole topic of death). It challenges the ways in which we don’t face up to our mortality very well. We end up spending an inordinate amount of money in the last year of someone’s life on drugs which have a lottery-ticket chance of working, when all the time, we could help people live longer and more comfortably if we introduced

Atul Gawande, another hero, has written powerfully in his book ‘Being Mortal’ (a manifesto for change in how the medical profession deals with the whole topic of death). It challenges the ways in which we don’t face up to our mortality very well. We end up spending an inordinate amount of money in the last year of someone’s life on drugs which have a lottery-ticket chance of working, when all the time, we could help people live longer and more comfortably if we introduced hospice care earlier and treated people with compassion. We are looking to launch compassionate communities here, where we are not afraid to talk about the difficult issues of life. We want people to have the kind of care that allows them to make supported choices to live well, right to the end. Our BCT Matron, Alison Scott, is a true champion of this cause, along with Dr Pete Nightingale, the recent RCGP national lead of palliative care, Dr Nick Sayer, Palliative Care Consultant and Sue McGraw, CEO of St John’s Hospice.

hospice care earlier and treated people with compassion. We are looking to launch compassionate communities here, where we are not afraid to talk about the difficult issues of life. We want people to have the kind of care that allows them to make supported choices to live well, right to the end. Our BCT Matron, Alison Scott, is a true champion of this cause, along with Dr Pete Nightingale, the recent RCGP national lead of palliative care, Dr Nick Sayer, Palliative Care Consultant and Sue McGraw, CEO of St John’s Hospice.

From the moment of conception to the moment of death, we want people to have optimal health in Morecambe Bay. We want people to be able to live well in the context of sometimes very disabling and difficult circumstances and illness. We want to see care wrapped around a person, recognising that this cannot always be provided for by the current ‘system’.

Better Care Together

Before the government launched its five year forward view for the NHS, we were already in the process of learning to work very differently here, around the Bay. We have been blurring the boundaries between various care organisations (including the acute trust, the mental health trust, the GP practices – now forming into a more cohesive federation, community nursing in its various forms, the police, the fire-service, local schools, the voluntary sector, the county council and social services), building relationships between clinical leaders, sharing the burdens of financial choices and care conundrums, strengthening the pillars of the various players, redesigning care pathways across the clinical spectrum to ensure better care for patients and infusing everything we do with integrated IT.

Before the government launched its five year forward view for the NHS, we were already in the process of learning to work very differently here, around the Bay. We have been blurring the boundaries between various care organisations (including the acute trust, the mental health trust, the GP practices – now forming into a more cohesive federation, community nursing in its various forms, the police, the fire-service, local schools, the voluntary sector, the county council and social services), building relationships between clinical leaders, sharing the burdens of financial choices and care conundrums, strengthening the pillars of the various players, redesigning care pathways across the clinical spectrum to ensure better care for patients and infusing everything we do with integrated IT.

The creation of integrated care communities (ICC) is at the heart of the vision to transfer more care out of the hospital setting and back into the community, whilst ensuring that the funding follows the patient. Our care co-ordinators become the new first port of call for our most vulnerable or ‘at-risk-of-admisison’ citizens. The idea is to wrap care around a person in the community, with the appropriate services being called in. Many times a care coordinator can bring in help from allied professions/volunteers and avoid unnecessary admissions or overlap of services. This means less pressure on the Emergency department and less pressure on General practice. We are also working to ensure our Urgent Care provision is fit for purpose with GPs, NWAS (our ambulance/paramedic service) and Out of Hours care offering much more of a buffer for our Emergency Departments.

Radical Leadership and the Challenges Ahead

There are many challenges ahead and both local and national threats remain. We are steering a huge ship through an iceberg field, and the so the waters are dangerous. We risk a lack of transfer of funding towards General Practice making it difficult for appropriate ‘buy-in’ for the changes we need to see. GPs ourselves have some brave leaps of faith to make. We will not be able to guarantee more money in our own pockets, but we must decide between protecting what we know or federating more fully for a more sustainable and excellent provision of care in the future (providing better education and career development in the process). We risk disengagement from senior clinicians in our hospital trust if the vision is not fully owned and shared by all. We have huge risks associated with the truly shocking cuts being forced upon our county council and a destabilisation of social care. We risk our nursing care home provision causing a halt to the entire program due to the vast complexities involved. Political whims, rules and pressures often seems to knock the wind out of our sails and could still utterly destabilise and destroy what is tenderly being built here.

However, one of the things which I have found most encouraging here is the quality and attitude of the leadership. Andrew Bennett as the SRO for BCT and

However, one of the things which I have found most encouraging here is the quality and attitude of the leadership. Andrew Bennett as the SRO for BCT and  Jackie Daniels, the CEO of UHMBT (the acute trust), have built stunning teams of people! I have the privilege of sitting on the executive board for the CCG and we have exec to exec meetings with the acute trust, in particular. The truth about Better Care Together is that for some it may mean doing themselves out of a job, letting go of power, and choosing facilitation and servanthood over domination and self-preservation. Leadership that is determined by the future and is able to lay itself down for the sake of what is really needed in our communities is exactly the kind of leadership we need. The leadership here across the spectrum is brave, it is altruistic, it is kenarchic, it is relational and it is rooted in the community.

Jackie Daniels, the CEO of UHMBT (the acute trust), have built stunning teams of people! I have the privilege of sitting on the executive board for the CCG and we have exec to exec meetings with the acute trust, in particular. The truth about Better Care Together is that for some it may mean doing themselves out of a job, letting go of power, and choosing facilitation and servanthood over domination and self-preservation. Leadership that is determined by the future and is able to lay itself down for the sake of what is really needed in our communities is exactly the kind of leadership we need. The leadership here across the spectrum is brave, it is altruistic, it is kenarchic, it is relational and it is rooted in the community.

And so we press on, knowing that we cannot remain as we are, knowing that in building together with our communities, we are finding that the future is not as bleak as it might otherwise be. Together we are wiser, braver and kinder. Morecambe Bay is no longer the butt of the jokes. It is becoming a place of hope, a place of potential, a light that is beginning to burn, dare I say it – a place shaped by love. It will be a place where health abounds in the beauty that surrounds.

I went to London a couple of weeks ago for the IHI (Institute for Health Innovation) conference in London – Quality Forum 2017. The focus was on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, with some hugely surprising and refreshing perspectives from around the world. It was absolutely great and I learnt loads. I’ve tried to distill my learning from the time into a single sheet diagram. My hope, over the next few blogs is to unpack this a bit more, but here is a very brief summary:

I went to London a couple of weeks ago for the IHI (Institute for Health Innovation) conference in London – Quality Forum 2017. The focus was on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, with some hugely surprising and refreshing perspectives from around the world. It was absolutely great and I learnt loads. I’ve tried to distill my learning from the time into a single sheet diagram. My hope, over the next few blogs is to unpack this a bit more, but here is a very brief summary:

If you take the work of Steve Peters (of “The Chimp Paradox” fame) seriously, which I do, then you can see Chimps at work everywhere in the NHS right now (and I’m not taking a cheap shot at Jeremy Hunt). For those of you, who have no idea what I’m talking about, then do read the book….but a brief precis is this: each of us are two people – we are both simultaneously an emotionally driven, primal chimp and a more rational human being. When faced with difficult circumstances, our chimps all too easily take over and our behaviour is driven by our emotions, because our human also feels insecure and we lose hold of our values (the computer part of our brains) which is able to alter our chimp behaviour.

If you take the work of Steve Peters (of “The Chimp Paradox” fame) seriously, which I do, then you can see Chimps at work everywhere in the NHS right now (and I’m not taking a cheap shot at Jeremy Hunt). For those of you, who have no idea what I’m talking about, then do read the book….but a brief precis is this: each of us are two people – we are both simultaneously an emotionally driven, primal chimp and a more rational human being. When faced with difficult circumstances, our chimps all too easily take over and our behaviour is driven by our emotions, because our human also feels insecure and we lose hold of our values (the computer part of our brains) which is able to alter our chimp behaviour. feel about what is happening in General Practice, Community Nursing/Therapy and indeed the NHS at large and it becomes easy to function out of raw emotion, heading into ‘rant mode’ or a strong defensive posture with the rest of my pride. But I have found it brings division. It pits my practice against another or General Practice at scale against the Hospital Trust or the government or whoever. But it doesn’t actually solve anything. It stares the problem in the face and hollers at it or throws faeces at it, and other than being cathartic (which has it’s place for a while), it doesn’t engage with a creative or collaborative process about how we face the future. The facts are right in front of us, and there is some thought about how to make General Practice strong enough to survive, be that through giant mergers or the formation of federations. Here in Morecambe Bay, we are experimenting with both those options and also trying to work in Integrated Care Communities (incorporating all our community partners) according to geographical locations.

feel about what is happening in General Practice, Community Nursing/Therapy and indeed the NHS at large and it becomes easy to function out of raw emotion, heading into ‘rant mode’ or a strong defensive posture with the rest of my pride. But I have found it brings division. It pits my practice against another or General Practice at scale against the Hospital Trust or the government or whoever. But it doesn’t actually solve anything. It stares the problem in the face and hollers at it or throws faeces at it, and other than being cathartic (which has it’s place for a while), it doesn’t engage with a creative or collaborative process about how we face the future. The facts are right in front of us, and there is some thought about how to make General Practice strong enough to survive, be that through giant mergers or the formation of federations. Here in Morecambe Bay, we are experimenting with both those options and also trying to work in Integrated Care Communities (incorporating all our community partners) according to geographical locations. If we are going to find solutions to the needs of the people we serve and develop together (no matter what is being shaped from the centre) a future healthcare model that works, GPs may need to let go of our power, as we have known it and embrace a different way of being. I think a possible solution lies with the co-operative movement as this would allow a truly integrative model to develop that benefits all our workers, no matter what their role, giving us the cultural environment in which innovation, excellence, learning, creativity and compassion could really flourish. Due to the nature of co-operatives and the principles at their core, a powerful force could be released which provides alternative solutions for a more equitable society.

If we are going to find solutions to the needs of the people we serve and develop together (no matter what is being shaped from the centre) a future healthcare model that works, GPs may need to let go of our power, as we have known it and embrace a different way of being. I think a possible solution lies with the co-operative movement as this would allow a truly integrative model to develop that benefits all our workers, no matter what their role, giving us the cultural environment in which innovation, excellence, learning, creativity and compassion could really flourish. Due to the nature of co-operatives and the principles at their core, a powerful force could be released which provides alternative solutions for a more equitable society. styles, from John Lewis to Mondragon, or the model adopted by Jos de Blok in the Netherlands. But the reason I like it so much, is that it takes power from the few and shares it with the many. It allows for a different style of leadership and a different mode of making decisions. Collaborative conversations and compassionate care of one another in providing care to the wider community becomes the order of the day with leadership that is both clinical and managerial but modeled on financial benefits for everybody and cooperation of wider teams of people.

styles, from John Lewis to Mondragon, or the model adopted by Jos de Blok in the Netherlands. But the reason I like it so much, is that it takes power from the few and shares it with the many. It allows for a different style of leadership and a different mode of making decisions. Collaborative conversations and compassionate care of one another in providing care to the wider community becomes the order of the day with leadership that is both clinical and managerial but modeled on financial benefits for everybody and cooperation of wider teams of people. There are draw backs and co-operatives are not perfect, but they are a solution that should be seriously considered as General Practice tries to navigate itself into the future. They can be complex to set up, but I would argue that complexity is worth it when it offers a solution that lasts longer than a more straight forward quick-fix that may not make it past a decade or two. Are we brave enough to explore solutions that dis-empower us for the sake of a better future for everyone?

There are draw backs and co-operatives are not perfect, but they are a solution that should be seriously considered as General Practice tries to navigate itself into the future. They can be complex to set up, but I would argue that complexity is worth it when it offers a solution that lasts longer than a more straight forward quick-fix that may not make it past a decade or two. Are we brave enough to explore solutions that dis-empower us for the sake of a better future for everyone?

the Nation State is beginning to crumble all around us. Let me just repeat that difficult statement in another way. The grandfather that is the Nation State is now utterly riddled with a cancer and it is dying. The cancer, like all cancers needs ever increasing growth in order to sustain it’s life and our economy is set up to feed it, but even built on the pyramid of power, control and debt, it can no longer survive. Like any dying man, it is holding on for dear life and as it does so, it puts the squeeze ever tighter on to health, education and other public services, pretending it is still powerful, controlling public services through the slashing of budgets and ever tighter and undeliverable targets whilst not actually dealing with it’s debt issue at all, but telling us all a story that it is. And the mouth of

the Nation State is beginning to crumble all around us. Let me just repeat that difficult statement in another way. The grandfather that is the Nation State is now utterly riddled with a cancer and it is dying. The cancer, like all cancers needs ever increasing growth in order to sustain it’s life and our economy is set up to feed it, but even built on the pyramid of power, control and debt, it can no longer survive. Like any dying man, it is holding on for dear life and as it does so, it puts the squeeze ever tighter on to health, education and other public services, pretending it is still powerful, controlling public services through the slashing of budgets and ever tighter and undeliverable targets whilst not actually dealing with it’s debt issue at all, but telling us all a story that it is. And the mouth of

h and among the communities most affected. Leaders must learn to ‘hold the space open’ for the new to emerge. It will mean understanding that we must make choices about which targets we do and don’t decide to meet, prioritising some services over others and taking better care of ourselves individually and in community. But it is not a time to lose hope! There is much goodness to come, much rediscovering to take place. Much creative reimagining to enjoy. Many songs to be sung. So, let’s face the music and dance.

h and among the communities most affected. Leaders must learn to ‘hold the space open’ for the new to emerge. It will mean understanding that we must make choices about which targets we do and don’t decide to meet, prioritising some services over others and taking better care of ourselves individually and in community. But it is not a time to lose hope! There is much goodness to come, much rediscovering to take place. Much creative reimagining to enjoy. Many songs to be sung. So, let’s face the music and dance.