I’m just returning from 36 hours with the Coalition of Partners for Europe, as part of the World Health Organisation. There were a further 2 days of conversations to occur, but I needed to get back to Morecambe Bay. I have learned so much during my short time with this amazing group of people, some new things and other things learning at a new depth or from a different perspective. I am again bowled over by how using tools from the Art of Hosting can bring a diverse group of people, across languages and cultures together to have really important conversations. Rather than write this in long paragraphs, I’m simply going to bullet my learnings, some of them personal, some more corporate, some amusing, some difficult. One thing is for sure: I know much less than I thought I knew!

I’m just returning from 36 hours with the Coalition of Partners for Europe, as part of the World Health Organisation. There were a further 2 days of conversations to occur, but I needed to get back to Morecambe Bay. I have learned so much during my short time with this amazing group of people, some new things and other things learning at a new depth or from a different perspective. I am again bowled over by how using tools from the Art of Hosting can bring a diverse group of people, across languages and cultures together to have really important conversations. Rather than write this in long paragraphs, I’m simply going to bullet my learnings, some of them personal, some more corporate, some amusing, some difficult. One thing is for sure: I know much less than I thought I knew!

1) Finland is 100 years old this year. It has a fascinating history. They also have one of the best Public Health systems in the world and are huge at tackling the social determinants of health. We have much to learn from them and their Scandinavian neighbours.

1) Finland is 100 years old this year. It has a fascinating history. They also have one of the best Public Health systems in the world and are huge at tackling the social determinants of health. We have much to learn from them and their Scandinavian neighbours.

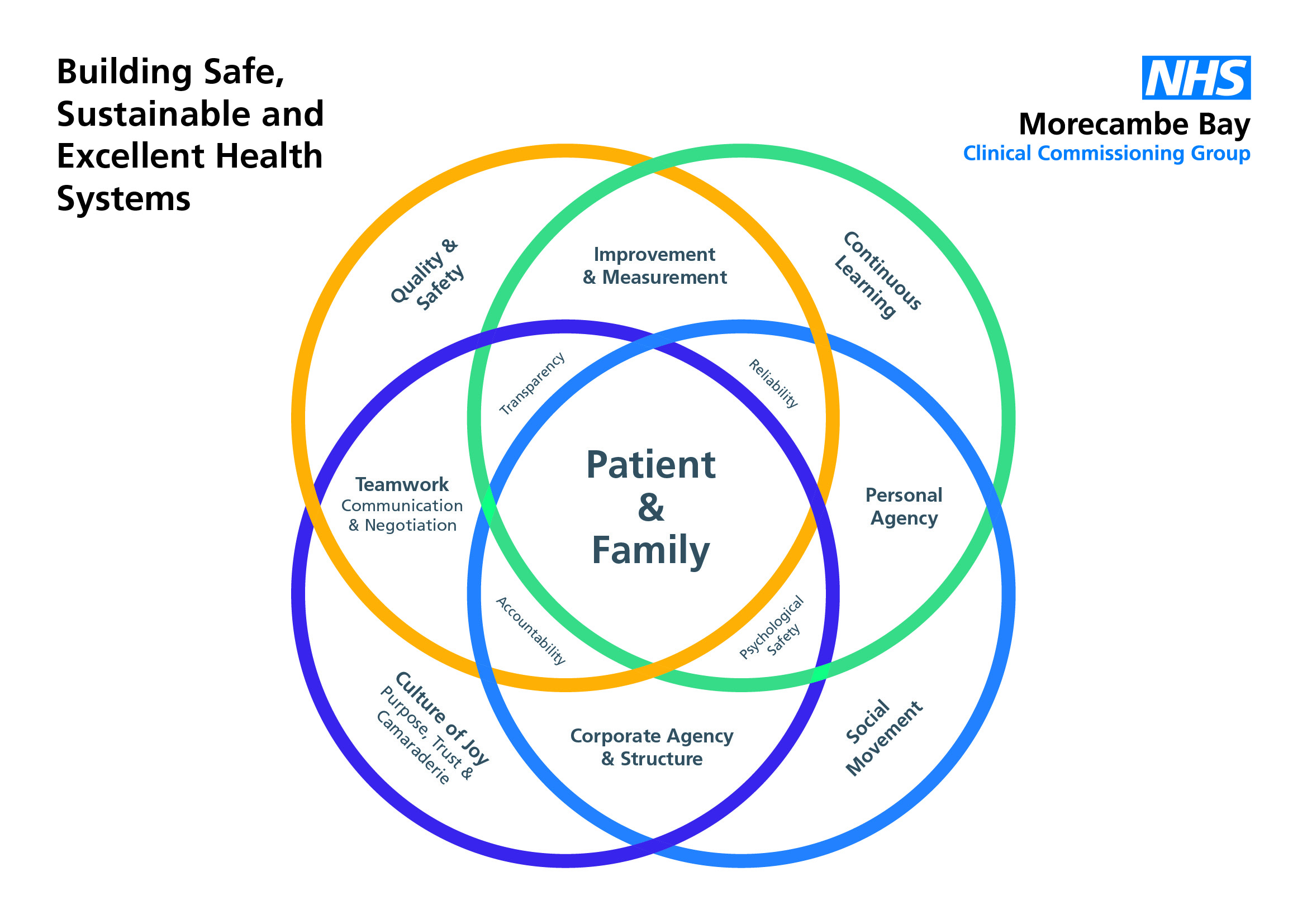

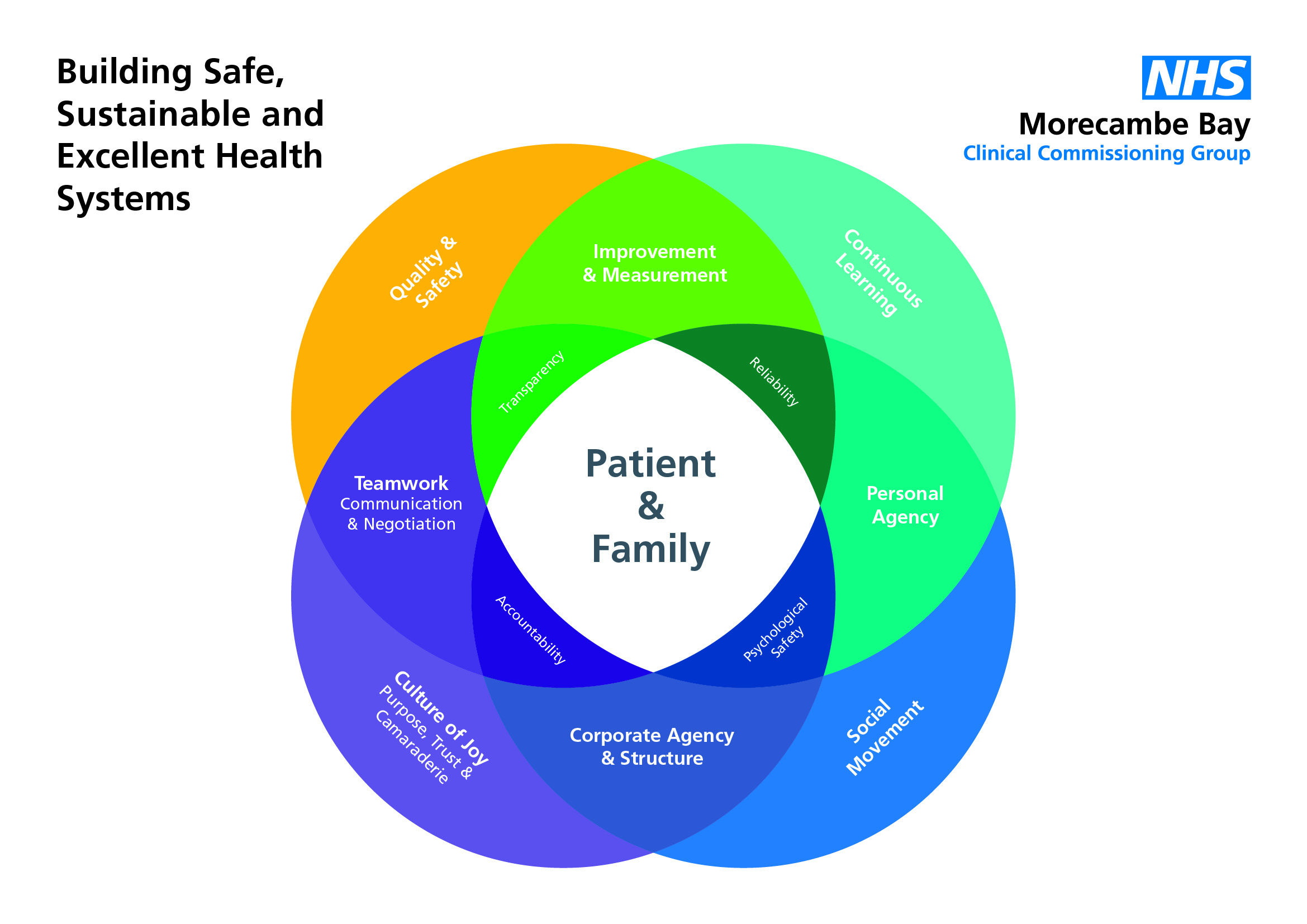

2) People LOVE the idea of a Culture of Joy! There is a tiredness to the WHO but a recognition across the board that there is a need for cultural change and that culture determines an enormous amount in terms of how well organisations function. Remember a culture of joy is built on good, honest, open, encouraging, kind, approachable and vulnerable leadership, with team members feeling a) that they belong and are loved/valued b) that they are trusted to do their work and c) they share a strong sense of vision.

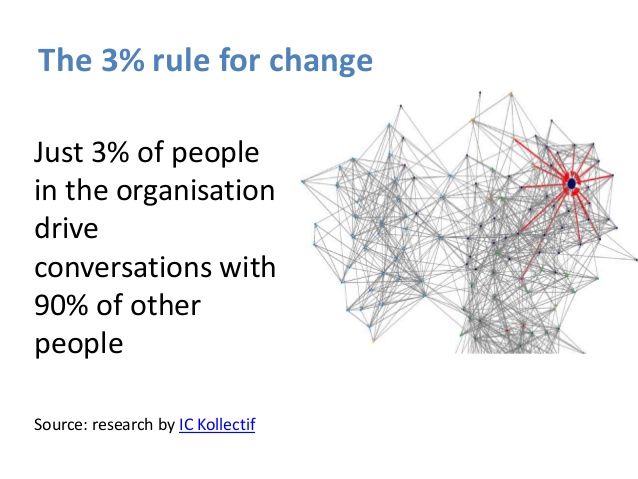

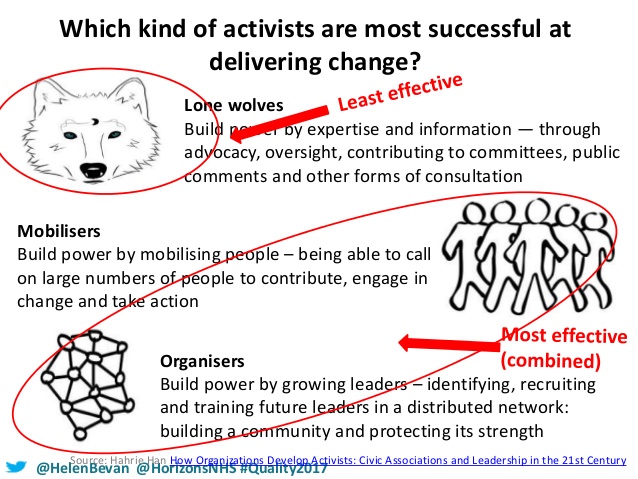

3) There is wide recognition that Social Movements are vital if we are going to break down health inequalities and see the health and wellbeing of all people improve. We simply cannot come up with ideas in board rooms and ‘do them’ to communities. However, there is also fantastic data and learning available to communtities, which can fuel the social movement. Public Health and Primary care must not sit as separate to or aloof from this emerging movement, but must be a key player and protagonist.

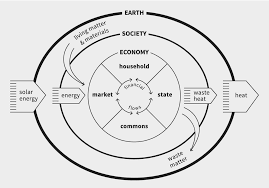

4) When dealing with complex systems, it is good to think of them as gardens instead of machines. To whom does the garden of public health belong? Public Health belongs to the public – it is part of the commons. Therefore communities need to be more involved. There are some great examples of community engagement from across Europe. However, we must move from consultancy to co-production and co-design.

5) Helping people live longer at a poorer quality of life is a pointless goal. The league tables and goals we develop must be co-designed with communities. Our markers of health and wellbeing need some reassessment.

6) People everywhere in the Western world are scared of talking about death and this has huge implications for how we spend money in our health systems.

7) Our European history is so fragile. This causes its own complexities when European people meet together – it all comes into the room with us and requires grace and kindness as we communicate. The quality of relationships within the coalition is fantastic, but more time is needed to develop this.

8) When trying to drink a yoghurt in a taxi, it is important to seal your lips around it well, otherwise you spill it all down your front and look like an idiot.

9) Public health and Primary Care are the bedrock of any health system. I knew this already, but the evidence from around the World is staggering. If these two foundation stones fail, and the staff who deliver these services are not cared for, the entire system collapses.

10) The UK has some of the best public health systems of anywhere in the world. However, the world is watching the decimation of our public health services with dismay. The vital role of prevention and protection that public health has must never be underestimated. If we do not invest in prevention, the consequences for the health system is devastating. The reorganisation of Public Health into our county councils has seen profound cuts to the budgets, as councils have removed the ring fenced budgets. This will almost certainly have detrimental consequences, especially when it comes to tackling our most difficult health and wellbeing issues.

11) When people tell you that all saunas are naked, this may not actually be true and you might end up feeling pretty awkward!

12) We have much to learn from other areas and nations. Shared learning is key. We can do this without competition, hierarchy or lording it over each other.

13) Building good relationships is everything.

14) There is a new generation of leaders emerging who are able to deal with complexity, refusing old silos, borders and hierarchies and finding ways to collaborate through good, honest and vulnerable relationships.

15) We need to learn to hold expertise in one hand and humility in the other. The expertise in epidemiology and the mapping of our health and social issues is vital, if we are going to close the health inequality gaps.

16) Public health is dependent on building partnerships. The wider social determinants of health (poverty, housing, adverse childhood experiences, loneliness, education, environmental issues etc) cannot be tackled by the meagre Public Health budgets. Coalition, collaboration and cooperation across many sectors are necessary for us to begin to tackle these hugely complex social justice issues.

17) Due to public health being underfunded, it leaves it wide open to abuse from those who hold the money strings. Lobbies, donors and national governments hold huge power in determining what does and does not receive funding, often despite the evidence.

18) We need leaders who understand the importance of gift economy and making investments into areas which will not serve their ego nor their profile, but will cause huge benefit to many people.

19) Collecting really good data is important. We need to learn to use it well to shape the conversations and change policy and legislation.

20) Public health holds a hugely important voice in calling governments to account for policy decisions that are to the detriment of a nations health. There is now clear evidence that austerity economics is really bad for people’s physical and mental health and is actually causing people to die. Theory must be challenged hard when evidence does not support it.

21) The poverty truth commission has so much to teach us. No decision about me, without me is for me. this statement made a profound impact on some of the delegates.

22) Doughnut Economics has caught the attention of the coalition.

23) Fazer chocolate is delicious.

24) One of the most challenging truths I learned is that it is often public health workers and doctors/clinicians working on the front line, who are the biggest barriers to working differently with communities and ironically get in the way of the very thing they would love to see happen. This has more to do with the ways we train people to think and work than anything else.

25) Although my talk went well and was hugely well received, I am learning more about the power of story and how to tell our story more effectively.

26) I am grateful that the coalition of partners does not depend on membership of the EU but I am more aware of the pain that Brexit is causing both for me personally and for many friends across Europe.

I understand that Brexit is happening, but day by day it feels to be one of the worst decisions we have ever made as a nation. It is going to cost us over £50 billion to leave, cause untold issues for our ability to trade, decimate the 3rd sector (which btw is the only thing right now stopping our public services from completely collapsing), undo so much great work built through the partnership of our nations and not deliver on any of the false promises made around extra money for our health system or solve our ‘migration issue’. Yes, the EU needs to change, but we have made a monumental error in leaving, rather than reforming it and I still feel we should just apologise and rebuild our bridges rather than burn them.