Last week the Chief Medical Officer, Professor Chris Whitty, came up to Lancashire. He spent the morning in Blackpool and then came over to see us in Morecambe Bay for the afternoon. It was an absolute pleasure to meet him and to welcome him here. He came to listen – the mark a genuinely kind and caring leader. More importantly he came to listen to people who live in these Northern Coastal Communities, to really hear what life is like and to allow that to impact his thinking and he prepares to develop further strategy on tackling poverty and health inequalities. As an epidemiologist, he is grounded in data and understands the issues at hand. What I really valued was his humanity and humility as he listened to the stories of people who live and work here.

Last week the Chief Medical Officer, Professor Chris Whitty, came up to Lancashire. He spent the morning in Blackpool and then came over to see us in Morecambe Bay for the afternoon. It was an absolute pleasure to meet him and to welcome him here. He came to listen – the mark a genuinely kind and caring leader. More importantly he came to listen to people who live in these Northern Coastal Communities, to really hear what life is like and to allow that to impact his thinking and he prepares to develop further strategy on tackling poverty and health inequalities. As an epidemiologist, he is grounded in data and understands the issues at hand. What I really valued was his humanity and humility as he listened to the stories of people who live and work here.

Last year, the Home Secretary, Pritti Patel also visited Morecambe Bay. She came to Barrow-in-Furness and spent some time at The Well, a CIC which works with people in recovery from addiction and of which I am a Director. In an interview afterwards, she was asked about the impact of Austerity and the reality of poverty in communities like ours (4 in 10 children in Barrow grow up in poverty). Her answer was that poverty is not the (sole) responsibility of government. I put sole in brackets, because she tried to insinuate that the role of central government in tackling poverty that exists in local areas is very minimal compared to the responsibility of local government (who have had their funding massively cut by central government in the last 10 years), local schools, local public services and local businesses. I’ve really wrestled with what she said since that time because she’s not altogether wrong! But nor is she right! Of course Central Government has a huge role to play in tackling poverty. It’s undeniable that national policy, economic strategy, including taxation, land ownership and business development all have massive implications. But poverty doesn’t only exist because of Central Government. Health Inequalities do not just exist because of Central Government. I am not for one minute, negating or

Last year, the Home Secretary, Pritti Patel also visited Morecambe Bay. She came to Barrow-in-Furness and spent some time at The Well, a CIC which works with people in recovery from addiction and of which I am a Director. In an interview afterwards, she was asked about the impact of Austerity and the reality of poverty in communities like ours (4 in 10 children in Barrow grow up in poverty). Her answer was that poverty is not the (sole) responsibility of government. I put sole in brackets, because she tried to insinuate that the role of central government in tackling poverty that exists in local areas is very minimal compared to the responsibility of local government (who have had their funding massively cut by central government in the last 10 years), local schools, local public services and local businesses. I’ve really wrestled with what she said since that time because she’s not altogether wrong! But nor is she right! Of course Central Government has a huge role to play in tackling poverty. It’s undeniable that national policy, economic strategy, including taxation, land ownership and business development all have massive implications. But poverty doesn’t only exist because of Central Government. Health Inequalities do not just exist because of Central Government. I am not for one minute, negating or diminishing their role, but we do have to all ask ourselves why we see and tolerate such inequality and what we can all do to change this narrative. Because as Michael Marmot reminds us so powerfully in his book ‘The Health Gap’ – none of this is inevitable and it certainly doesn’t have to continue. Marmot holds that “if you want to understand why health is distributed the way it is, you have to understand society.” So if we want to understand society, then as Prof Bev Skeggs (Professor of Sociology at Lancaster University) so eloquently says: “Society is shaped by our values and what we value“.

diminishing their role, but we do have to all ask ourselves why we see and tolerate such inequality and what we can all do to change this narrative. Because as Michael Marmot reminds us so powerfully in his book ‘The Health Gap’ – none of this is inevitable and it certainly doesn’t have to continue. Marmot holds that “if you want to understand why health is distributed the way it is, you have to understand society.” So if we want to understand society, then as Prof Bev Skeggs (Professor of Sociology at Lancaster University) so eloquently says: “Society is shaped by our values and what we value“.

If we are serious about ‘levelling up’, ‘resetting’ and tackling age old health inequalities then we have to understand that this is both complex, but also entirely possible and need not take 100 years! As Marmot says in his amazing book ‘The Health Gap’ – essential reading for anyone who cares about this issue – we must do something and we must do it now! Marmot’s research proves that health inequalities are not a footnote to the health problems we face, they are the major health problem. We can actually make significant and measurable differences in a short space of time – so why aren’t we doing more? In the rest of this blog I hope to look at how we can make a real difference to poverty and health inequalities in our communities. We all have a part to play, no matter who we are. This is absolutely an issue for central and local government, but it is also an issue for society as a whole in all its facets.

If we are serious about ‘levelling up’, ‘resetting’ and tackling age old health inequalities then we have to understand that this is both complex, but also entirely possible and need not take 100 years! As Marmot says in his amazing book ‘The Health Gap’ – essential reading for anyone who cares about this issue – we must do something and we must do it now! Marmot’s research proves that health inequalities are not a footnote to the health problems we face, they are the major health problem. We can actually make significant and measurable differences in a short space of time – so why aren’t we doing more? In the rest of this blog I hope to look at how we can make a real difference to poverty and health inequalities in our communities. We all have a part to play, no matter who we are. This is absolutely an issue for central and local government, but it is also an issue for society as a whole in all its facets.

Prof Imogen Tyler has written a phenomenal book called ‘Stigma: The Machinery of Inequality’. It is, in my opinion, the most important book published this year (I  know that sounds like an overstatement, but it isn’t!). I believe this must be our starting point when we talk about poverty and health inequality. If we don’t understand how we have all subconsciously and/or overtly accepted a narrative that ‘the poor are feckless and lazy and could just pull themselves up by their boot straps if they wanted to, because we all have the same opportunities,’ then we are blind to the reality of the stigma that surrounds poverty and how it is weaponised to maintain the status quo. The thing is – it’s not just the government who have used this narrative – it’s part of British culture. So many of our comedy programmes ridicule and scapegoat the poorest in our society – The Harry Enfield Show (‘The Slobs’), and Little Britain (Vicky Pollard) to name just two. think of how many reality TV shows, like ‘Benefits Street’ have reinforced the stereotypes. Our national press continue to bombard us with very particular perspectives on ‘benefits scroungers‘ and ‘migrant swarms‘ and we read it, we drink it in, and whether we like it or not, it embeds itself as a way of thinking in our minds. That’s how propaganda works. It creates a corporate mindset by ‘othering’ our fellow human beings and pitting us against one another, rather than bringing us together to collaboratively find solutions in a way that works for everyone. It takes significant and sustained effort to do our own internal work around stigma, racism, white privilege, sexism and toxic masculinity. But if we want to build a society shaped by our values and what we really value then whoever we are – this is where we must begin. Our first work is to demolish the strongholds in our minds, challenge our unconscious biases and undo our ‘go to’ narratives, replacing them with deeper and better truths about the innate value in every human life. We must be determined to create the kind of language which reflects this because language gives substance to our thoughts and beliefs. This important work needs to weave its way through every part of our education system. This will take effect in shifting the corporate mindset through the way we teach history in our schools, for example, with a more honest appraisal of the negative effects of colonialism, or indeed how the feudal system continues to dominate the price of land and the unaffordability of good quality housing. We need to equip the rising generation with the tools they will need to undo the damaging ideologies of stigma and find solutions to the issues they are facing around social justice and climate change.

know that sounds like an overstatement, but it isn’t!). I believe this must be our starting point when we talk about poverty and health inequality. If we don’t understand how we have all subconsciously and/or overtly accepted a narrative that ‘the poor are feckless and lazy and could just pull themselves up by their boot straps if they wanted to, because we all have the same opportunities,’ then we are blind to the reality of the stigma that surrounds poverty and how it is weaponised to maintain the status quo. The thing is – it’s not just the government who have used this narrative – it’s part of British culture. So many of our comedy programmes ridicule and scapegoat the poorest in our society – The Harry Enfield Show (‘The Slobs’), and Little Britain (Vicky Pollard) to name just two. think of how many reality TV shows, like ‘Benefits Street’ have reinforced the stereotypes. Our national press continue to bombard us with very particular perspectives on ‘benefits scroungers‘ and ‘migrant swarms‘ and we read it, we drink it in, and whether we like it or not, it embeds itself as a way of thinking in our minds. That’s how propaganda works. It creates a corporate mindset by ‘othering’ our fellow human beings and pitting us against one another, rather than bringing us together to collaboratively find solutions in a way that works for everyone. It takes significant and sustained effort to do our own internal work around stigma, racism, white privilege, sexism and toxic masculinity. But if we want to build a society shaped by our values and what we really value then whoever we are – this is where we must begin. Our first work is to demolish the strongholds in our minds, challenge our unconscious biases and undo our ‘go to’ narratives, replacing them with deeper and better truths about the innate value in every human life. We must be determined to create the kind of language which reflects this because language gives substance to our thoughts and beliefs. This important work needs to weave its way through every part of our education system. This will take effect in shifting the corporate mindset through the way we teach history in our schools, for example, with a more honest appraisal of the negative effects of colonialism, or indeed how the feudal system continues to dominate the price of land and the unaffordability of good quality housing. We need to equip the rising generation with the tools they will need to undo the damaging ideologies of stigma and find solutions to the issues they are facing around social justice and climate change.

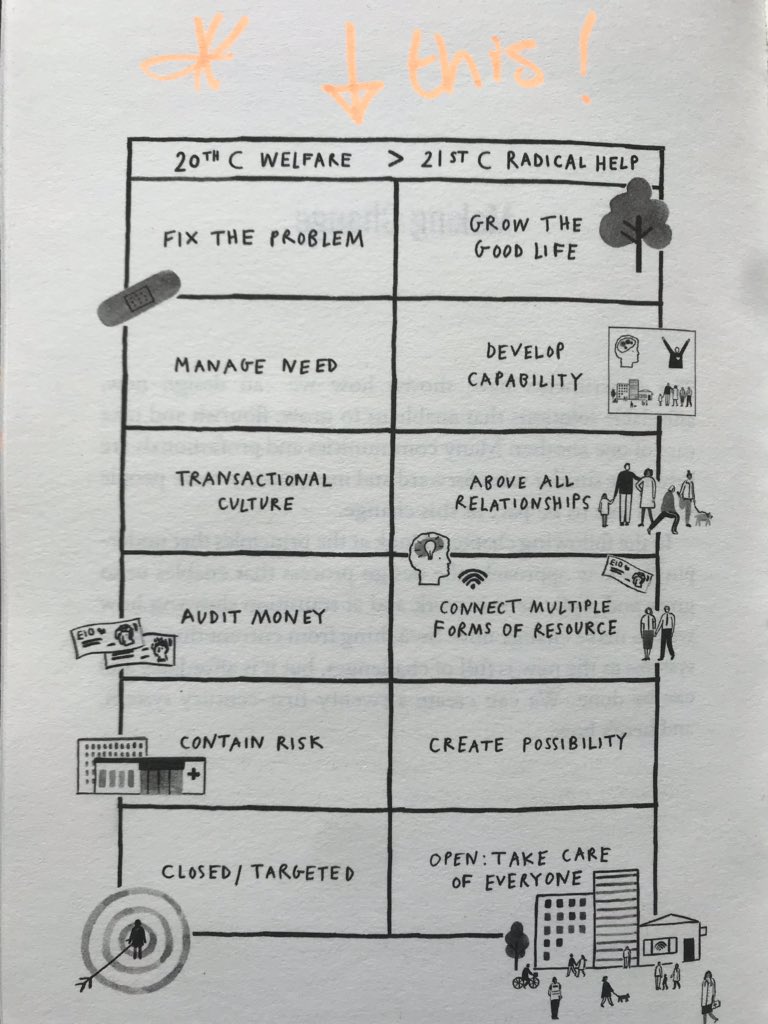

Imogen draws on the work of The Poverty Truth Commission, here in Morecambe Bay and in other places to highlight ways in which we can break down stigma, build friendships and create a kinder society. The Poverty Truth Commission gives us a real insight not only into how we break down stigma, but how the building of friendships across the dividing walls in our society creates a new political space from which we can create ‘the good life’ together. Our political systems have become far too removed from every day life and we need a radical shift from disengagement to much wider participation in community life and decision making. There are so many voices calling for this from all sides of the political spectrum. We so badly need to break out of our entrenched twitter-siloed positions and learn to curate the space for a more collaborative and co-operative form of political and economic conversation and prioritisation. It is, in my view, impossible to think about breaking down health inequalities without involving those who experience them most severely to be a part of finding the solutions. For further reading on this: Radical Help by Hilary Cottam, Rekindling Democracy by Cormac Russell and Greed is Dead: Politics After Individualism by Paul Collier and John Kay are all vital texts. This requires a much more local, devolved, participatory kind of politics – the kind of thing made possible through initiatives like ‘The Art of Hosting’, ‘Citizens Jurys’ and ‘People’s Assemblies’ underpinned by principles of love and kindness. In this way we can create much more realistic ‘deals’ (like the one in Wigan) between public sector organisations and people in our communities. This might all sound a bit wishy washy, but as Marmot demonstrates, “the lower people are in the socio-economic hierarchy, the less control people have over their lives.’ He argues that “tackling disempowerment is crucial for improving health and improving health equity” This is where the circular arguments about absolute or relative poverty are missing the point. When Philip Hammond stated as Chancellor of the Exchequer that he ‘doesn’t see poverty in the UK‘ – he was talking about absolute poverty and implying it isn’t an issue in the UK. He’s profoundly wrong. Economist Amartya Sen helps us understand this: “Relative inequality with respect to income translates into absolute inequality in capabilities: your freedom to be and do. It is not only how much money you have that matters for your health, but what you can do with what you have; which in turn, will be influenced by where you are.” Marmot argues that this means people in this position cannot participate in society with dignity. It is this active participation in ones own life and the life of the community around you, coupled with a sense that you can be part of the change that needs to happen which underpins the strap line for the poverty truth commission. “Nothing about us, without us, is for us.” If we want to tackle poverty and health inequalities in our society we have to radically include those who are currently most marginalised to be part of the change with us. We’re not trying to fix them. Together, we are trying to untangle the injustice that allows this kind of staggering inequality to continue.

Imogen draws on the work of The Poverty Truth Commission, here in Morecambe Bay and in other places to highlight ways in which we can break down stigma, build friendships and create a kinder society. The Poverty Truth Commission gives us a real insight not only into how we break down stigma, but how the building of friendships across the dividing walls in our society creates a new political space from which we can create ‘the good life’ together. Our political systems have become far too removed from every day life and we need a radical shift from disengagement to much wider participation in community life and decision making. There are so many voices calling for this from all sides of the political spectrum. We so badly need to break out of our entrenched twitter-siloed positions and learn to curate the space for a more collaborative and co-operative form of political and economic conversation and prioritisation. It is, in my view, impossible to think about breaking down health inequalities without involving those who experience them most severely to be a part of finding the solutions. For further reading on this: Radical Help by Hilary Cottam, Rekindling Democracy by Cormac Russell and Greed is Dead: Politics After Individualism by Paul Collier and John Kay are all vital texts. This requires a much more local, devolved, participatory kind of politics – the kind of thing made possible through initiatives like ‘The Art of Hosting’, ‘Citizens Jurys’ and ‘People’s Assemblies’ underpinned by principles of love and kindness. In this way we can create much more realistic ‘deals’ (like the one in Wigan) between public sector organisations and people in our communities. This might all sound a bit wishy washy, but as Marmot demonstrates, “the lower people are in the socio-economic hierarchy, the less control people have over their lives.’ He argues that “tackling disempowerment is crucial for improving health and improving health equity” This is where the circular arguments about absolute or relative poverty are missing the point. When Philip Hammond stated as Chancellor of the Exchequer that he ‘doesn’t see poverty in the UK‘ – he was talking about absolute poverty and implying it isn’t an issue in the UK. He’s profoundly wrong. Economist Amartya Sen helps us understand this: “Relative inequality with respect to income translates into absolute inequality in capabilities: your freedom to be and do. It is not only how much money you have that matters for your health, but what you can do with what you have; which in turn, will be influenced by where you are.” Marmot argues that this means people in this position cannot participate in society with dignity. It is this active participation in ones own life and the life of the community around you, coupled with a sense that you can be part of the change that needs to happen which underpins the strap line for the poverty truth commission. “Nothing about us, without us, is for us.” If we want to tackle poverty and health inequalities in our society we have to radically include those who are currently most marginalised to be part of the change with us. We’re not trying to fix them. Together, we are trying to untangle the injustice that allows this kind of staggering inequality to continue.

The NHS is currently exploring its own role in tackling poverty and health inequalities. As the biggest employer in the country it has the opportunity to make a massive difference as an Anchor Institution, setting a good example and creating a network, both locally and nationally for other partners to collaborate with. Along with other local employers it can make a vast difference through positive employment schemes for people from poorer communities, paying a living wage, procuring locally and developing apprenticeship schemes, to name just a few ideas. We have developed a charter in Lancashire and South Cumbria, which we hope will be nationally available soon. I’ve previously written on the role of Primary Care Networks (PCNs) and how taking a ‘radical help’ approach with our communities could make a real difference at a local level. PCNs have a particular role in Population Health Management. This approach that we are focusing on across Lancashire and South Cumbria uses the best in data science and enables health teams to focus in on the areas of greatest need, working with those communities to bring about change through co-creation. If the NHS is really serious about ‘levelling up’, however, one thing which must be explored is the national funding formula. If we’re serious about Population Health, we must be much more comfortable with allocating resources according to Indices of Multiple Deprivation. We must also change what we measure and ensure that Key Performance Indicators and clinical funding streams are much more aligned to this entire agenda. Incentives do change behaviour and we need to make sure that we’re getting them right, whilst permissioning PCNs, in particular, to have a change in focus. We need to make it more attractive to work in areas of higher complexity and create more sustainable models of care. It is my belief that without a Health Inequalities lead at the top table of NHS England and Improvement, the right level of accountability and prioritisation simply won’t be there. It won’t be enough just to have someone accountable in each system, vital though this is. Integrated Care Systems must take an evidence-based approach and recognise what a profound difference they can make in a short space of time. The drivers in the system must be wedded to this way of working. The NHS must stop spending such a colossal amount of money tinkering around the edges of helping people to live a bit longer and get deep into the game of tackling the vast and ongoing health inequalities in our society. It must use it’s powerful voice to continually challenge policies which make this worse and actively campaign to make society more equitable. Marmot and The King’s Fund have already detailed so much that the NHS can do. Olivia Butterworth and Sara Bordoley and their teams are doing some great things. We need more of it! It’s time to act!

The NHS is currently exploring its own role in tackling poverty and health inequalities. As the biggest employer in the country it has the opportunity to make a massive difference as an Anchor Institution, setting a good example and creating a network, both locally and nationally for other partners to collaborate with. Along with other local employers it can make a vast difference through positive employment schemes for people from poorer communities, paying a living wage, procuring locally and developing apprenticeship schemes, to name just a few ideas. We have developed a charter in Lancashire and South Cumbria, which we hope will be nationally available soon. I’ve previously written on the role of Primary Care Networks (PCNs) and how taking a ‘radical help’ approach with our communities could make a real difference at a local level. PCNs have a particular role in Population Health Management. This approach that we are focusing on across Lancashire and South Cumbria uses the best in data science and enables health teams to focus in on the areas of greatest need, working with those communities to bring about change through co-creation. If the NHS is really serious about ‘levelling up’, however, one thing which must be explored is the national funding formula. If we’re serious about Population Health, we must be much more comfortable with allocating resources according to Indices of Multiple Deprivation. We must also change what we measure and ensure that Key Performance Indicators and clinical funding streams are much more aligned to this entire agenda. Incentives do change behaviour and we need to make sure that we’re getting them right, whilst permissioning PCNs, in particular, to have a change in focus. We need to make it more attractive to work in areas of higher complexity and create more sustainable models of care. It is my belief that without a Health Inequalities lead at the top table of NHS England and Improvement, the right level of accountability and prioritisation simply won’t be there. It won’t be enough just to have someone accountable in each system, vital though this is. Integrated Care Systems must take an evidence-based approach and recognise what a profound difference they can make in a short space of time. The drivers in the system must be wedded to this way of working. The NHS must stop spending such a colossal amount of money tinkering around the edges of helping people to live a bit longer and get deep into the game of tackling the vast and ongoing health inequalities in our society. It must use it’s powerful voice to continually challenge policies which make this worse and actively campaign to make society more equitable. Marmot and The King’s Fund have already detailed so much that the NHS can do. Olivia Butterworth and Sara Bordoley and their teams are doing some great things. We need more of it! It’s time to act!

The issue of land and the lack of affordable housing has a huge effect on people being locked in cycles of poverty and creates massive health inequalities. Central Government has a huge role in sorting this out, but increased devolution may make it become easier with increased public participation in the daily politics of life. Most of the way our land is distributed and inflated was designed in the 11th Century and through the Middle Ages. Alistair Parvin has written the most phenomenal piece on this issue and it deserves time to be read and digested. He makes a very tight case as to why we find ourselves in the situation we are in, but encouragingly he comes up with some really possible, pragmatic and solutions-focused ideas about how we can solve this, if we want to. Of course there are many vested interested and people in positions of significant power, who would resist such an approach, but we must not let that stop us having some grown-up conversations about this. Parvin accepts that it would take a government with extraordinary vision and bravery to do what is really needed and offers some really helpful pragmatic smaller steps that would get us in the right direction.

I am not going to copy and paste his paper here, but I hope this whet’s your appetite enough to seriously engage in the possibilities. We can’t keep passing this ball to future generations. We have a once in a lifetime opportunity to reset our economy and in this time of ‘jubilee‘ we need to grasp this nettle if we are serious about creating a society that truly works for everyone. Mariana Mazzucato, Kate Raworth, Katherine Trebeck and Carlota Perez are just some of the brilliant people creating the kind of economic and technological frameworks we need. It’s time to build an economy of hope, shaped by our values and focusing on what we value. We know that the UK population would like us to place health and wellbeing at the heart of the UK economy instead of GDP – this is a massive shift and one that we must hold onto. This priority along with the creation of more social co-operatives, new local/community banks and credit unions would all help us to create a fairer economy that really works for the people.

So, we all have a role to play. As individuals, in our communities, through our work and via a more engaged, participatory, devolved, democracy, we need to deal with stigma and ‘wicked issues’, be determined to be more switched on, truly engaged and find together some pragmatic solutions fit for the 21st century. Disengagement is not an option. Let us not miss this moment. We can and we must do something. As Michael Marmot says in the final sentence of ‘The Health Gap’: “Do something. Do it more. Do it better.”